Spending on prescription and over-the-counter drugs in Canada is rising faster than spending on hospitals or doctors, according to the latest official snapshot of how health-care dollars are allocated across the country.

The total amount that individual Canadians, private insurers and governments pay for medications is expected to grow by 4.2 per cent this year, an increase driven in part by wider use of brand-name drugs that cost more than $10,000 a year.

By comparison, total spending on hospital care and physicians is expected to increase by 4 per cent and 3.1 per cent, respectively, in 2018.

In a new report published on Tuesday, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) said the over all growth in health-care spending in Canada in 2018, which is anticipated to be 4.2 per cent, is slightly higher than in the lean years after the 2009 recession, but lower than in the prosperous decade that preceded the crash.

Total health-care spending from all sources – public and private – is expected to top $253-billion this year. That works out to $6,839 for each Canadian, or the equivalent of 11.3 per cent of GDP, CIHI said.

“It’s a little bit steady-as-she-goes for national health expenditures,” Michael Hunt, the director of spending, primary care and strategic initiatives at CIHI, the official clearinghouse for national health-care statistics, said in an interview. “We’ve been looking at the 4-per-cent economic growth reflected in health-spending growth as well. It’s the magic 4 per cent.”

However, Mr. Hunt added that CIHI is keeping a close eye on prescription drugs as one area where spending could spike in coming years.

Health expenditure forecast for 2018, by use of funds

CIHI explored some of the reasons for concern in a separate report, also released on Tuesday, on what government-sponsored drug plans doled out for prescription drugs in 2017. (Public drug plans vary from province to province, but most provide some coverage for seniors, social-assistance recipients and patients with extremely high drug bills.)

“By historical standards, this growth in drug spending is not that huge. It’s fairly normal,” said Michael Law, a University of British Columbia professor who holds a Canada Research Chair in Access to Medicines. “But what you can see in here are the signs of what’s coming.”

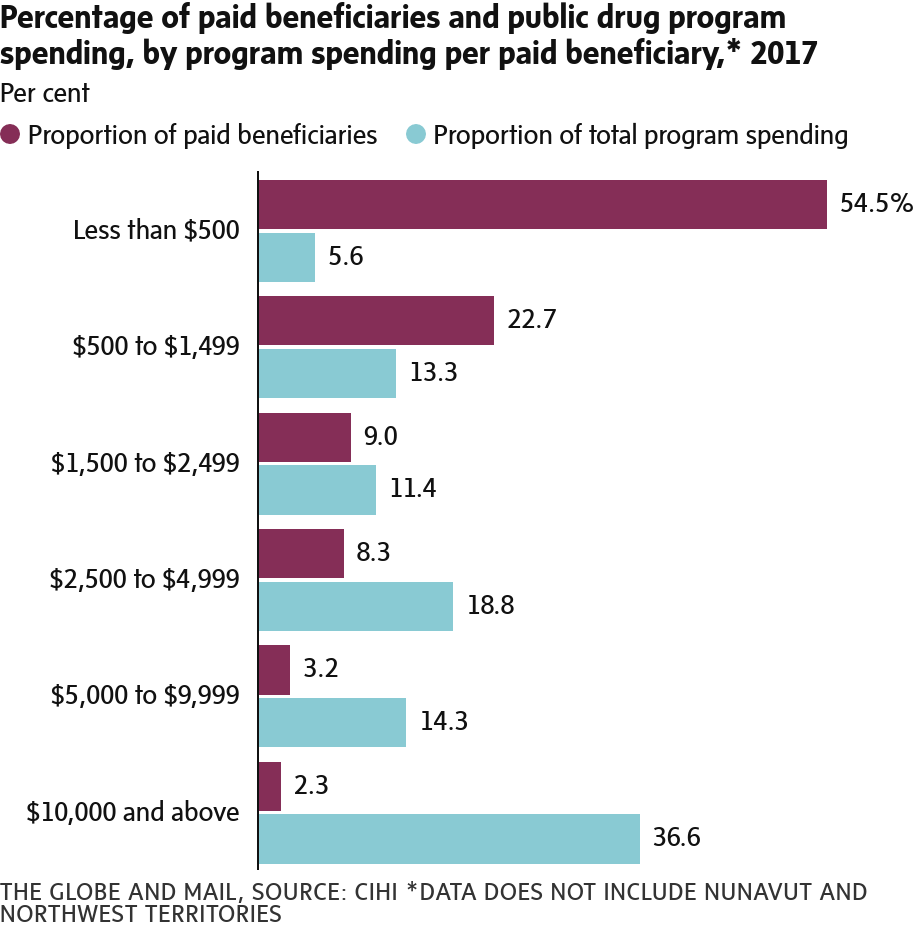

For example, the CIHI report on prescription drugs found that the proportion of government spending on patients whose medications cost more than $10,000 a year increased to 36.6 per cent in 2017, up from 34.5 per cent in 2016.

The report also pointed out that Canada has been slow to embrace biosimilars, the cheaper near-copies of biologic drugs. Biologics, which are manufactured in living cells rather than synthesized from chemicals like conventional pills, tend to be expensive: Three of the top-10 classes of drugs in terms of government spending are biologics.

At the top of that list is a class of drugs called tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, or anti-TNF drugs, which treat autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

In 2017, public drug plans spent more than $1.1-billion on anti-TNF drugs, including on infliximab, which is sold under the brand name Remicade, and etanercept, better known as Enbrel. The less-expensive biosimilar versions of both drugs accounted for only 1.4 per cent of spending on infliximab and etanercept last year.

“If we don’t figure out how to deal with biosimilars, we’re not going to experience the same thing that we have over the past decade where we saved a lot of money because a lot of drugs went generic,” Mr. Law said.

Savings from generic drugs have helped to offset the cost increases associated with the arrival of more high-priced drugs. A case in point: Public spending on the category of “other antidepressants,” fell by nearly 17 per cent from $235.9-million in 2016 to $196.4-million last year, largely because of the introduction of a generic version of one drug, duloxetine – better known as Cymbalta.

But Jordan Hunt, CIHI’s manager for pharmaceuticals, said drug spending shouldn’t be judged in isolation. “We need to think about health spending as a whole … a hep C drug might save the cost of a liver transplant,” he said, referring to an expensive new class of direct-acting antivirals that can clear hepatitis C infections in about three months.

On the whole, hospitals still gobble up more health-care dollars than any other part of the system – they are expected to account for 28.3 per cent of health spending in 2018. Prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs and personal health supplies are next, accounting for 15.7 per cent of spending, followed by doctors at 15.1 per cent.

Most of the remainder is taken up by spending on long-term-care homes, home care, vision care, dental care and public-health initiatives.

In 2017, Canada spent more per person on health care than the average among the prosperous countries that make up the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, but much less than its neighbour to the south. The United States spent $12,865 a person on health care last year, more than twice the Canadian figure for the same year.

KELLY GRANT

HEALTH REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, November 20, 2018