The Middle East remained on tenterhooks Thursday, trying to parse the confusing and often contradictory Twitter feed of U.S. President Donald Trump for clues as to what might happen next in Syria and across the region.

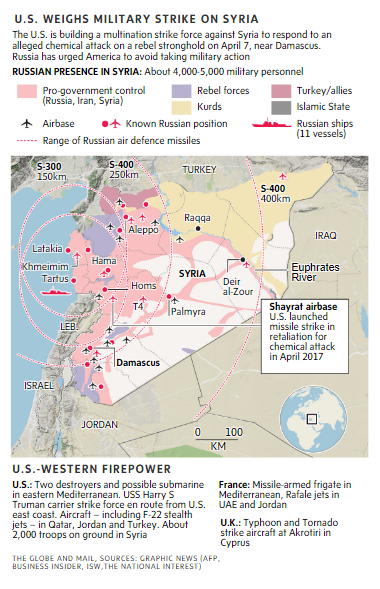

The timing of a U.S. military strike against Bashar al-Assad’s regime − which appeared imminent on Wednesday after Mr. Trump tweeted that Syria and its ally Russia should “get ready” − seemed less clear Thursday, as Mr. Trump seemed to reverse course with a subsequent Twitter declaration that an attack “could be very soon or not so soon at all!” Meanwhile, U.S. Defence Secretary James Mattis told a congressional committee that an attack “was not yet in the offing” amid worries about provoking a wider war with Syria’s ally, Russia.

But there was little doubt that some kind of military action − one that could trigger an uncertain response from Russia and other actors in the region − lies ahead.

“We are trying to stop the murder of innocent people,” Mr. Mattis said, referring to Mr. Trump’s stated aim of punishing Mr. al-Assad for his alleged April 7 chemical-weapons attack on the rebel-held town of Douma, on the outskirts of Damascus. “But on a strategic level, it’s how do we keep this from escalating out of control − if you get my drift on that.”

The challenge before Mr. Mattis and his staff is to design a military response significant enough to deter Mr. al-Assad from using his chemical arsenal again, without crossing an invisible line that would trigger a Russian response.

At the moment, a U.S.-led coalition is forming, backed by France and Britain. Whether military strikes will deter any future battlefield use of chemical weapons is doubtful: The Obama administration reached a deal in 2013 that was supposed to see Mr. al-Assad give up his chemical arsenal. That deal failed, and cruise-missile strikes that Mr. Trump ordered in the wake of another chemical-weapons attack proved to be only a short-term deterrent.

Russia, like Mr. Trump, has sent a series of mixed messages in recent days. On Tuesday, a Russian diplomat in Beirut told reporters that Russia – which has a significant military presence in Syria, where it has been helping Mr. al-Assad fight his country’s seven-year-old civil war − would target not only any incoming aircraft or missiles, but also the ships they were launched from.

Other Russian officials, however, have signalled that Russia would likely only respond if Russian forces in Syria came under direct threat.

Moscow insists there is no evidence that a chemical attack took place in Douma, claiming that online videos − including some that show dead and dying children with foam around their mouths − were fabricated by anti-Assad rebels. The Saudi-backed Jaysh al-Islam militia was in control of Douma until Sunday, when it retreated from the town shortly after the first evidence of the apparent chemical attack began to emerge.

Russian and Syrian troops took control of Douma on Thursday, ahead of an expected visit by a team of experts from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons ( OPCW ) that began arriving in Beirut on Thursday. But while the OPCW can carry out tests to determine if chemical weapons were used in Douma, it does not have a mandate to assess blame for any attacks.

On Thursday, French President Emmanuel Macron − who has suggested his country would take part in any punitive measures against the Assad regime − said France had “proof” the Syrian government carried out the attack on Douma, which left dozens of people dead.

“We have proof that last week chemical weapons were used, at least with chlorine, and that they were used by the regime of Bashar al-Assad,” Mr. Macron said in a television interview, without making any evidence public. “We will need to take decisions in due course, when we judge it most useful and effective.”

Britain is also expected to take part in any U.S.-led action against Syria. British Prime Minister Theresa May met with senior members of her cabinet for two hours on Thursday to discuss possible military action. No decision was made on a strike, officials from No. 10 said.

Ms. May later called Mr. Trump. According to a No. 10 official, “They agreed it was vital that the use of chemical weapons did not go unchallenged, and on the need to deter the further use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime. They agreed to keep working closely together on the international response.”

It’s not clear if Ms. May will seek approval from Parliament for any military action. Former prime minister David Cameron was humiliated by the House of Commons in 2013 when he lost a vote on a military strike after another alleged chemical-weapons attack by the Syrian government.

On the ground in the Middle East, expectations remained high Thursday that the United States and its allies would eventually launch some kind of military action against Syria.

Mr. al-Assad’s forces have reportedly been shuffling military assets around since Mr. Trump’s “get ready” tweet. On Thursday, there were reports suggesting that much of Syria’s air force had been moved to the protection of Russia’s Hmeymim Air Base in the northwest of the country in anticipation that Syrian airfields could be targeted, as they were a year ago when Mr. Trump ordered a barrage of cruise missiles after another alleged chemical attack by Mr. al-Assad’s forces.

Israel and Iran, meanwhile, continued to exchange threats, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu insisting that his country − which reportedly carried out a Sunday airstrike in Syria that killed 14 Iranians − would not allow Iran to establish military infrastructure on its doorstep. Ali Shirazi, a representative of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, warned that “Tel Aviv and Haifa will be destroyed” if Israel continued to confront Iran.

Trapped in the middle of it all is Lebanon, a country that has sectarian faultlines similar to those that split Syria apart. Lebanon has also been a frequent proxy battleground for regional conflicts, including a 2006 war that pitted Israel against the Iranian-backed Hezbollah militia.

Many in Beirut − just 85 kilometres from Damascus − are worried that it will get harder and harder for Lebanon to avoid getting sucked into the expanding war next door.

“There is no doubt that the worse is yet to come, as if this part of the world is forever doomed to remain mired in fire and blood,” read an editorial in the Daily Star, an English-language newspaper in the Lebanese capital. “We have to stay out of the approaching storm. There is no other way.”

MARK MACKINNON

Senior International Correspondent

The Globe and Mail, April 12, 2018