Canadian special forces soldiers are more directly engaged in the fight against Islamic State forces in Iraq than previously thought, with troops on the ground guiding air strikes against targets and using sniper fire to fend off enemy attacks at the front lines.

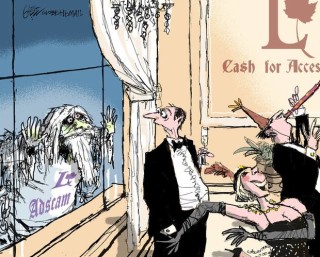

The release by the Canadian military on Monday has triggered a debate about whether mission creep is afflicting what was supposed to be a relatively limited assignment for nearly 70 elite soldiers to offer military advice to Kurdish fighters in northern Iraq.

The military and the Harper government insist these activities are not the kind of direct-combat ground operations that Canadians were assured troops would avoid in their role as instructors and trainers to peshmerga forces battling the Islamic State.

Brigadier-General Mike Rouleau, commander of Canadian Special Operations Forces Command, revealed in a media briefing on Monday that soldiers have directed air strikes against ground targets 13 times in the past seven or eight weeks, which means guiding attacks by methods such as “marking the target with a laser so the bomb hits precisely where you want it to hit.”

The senior officer defended this apparent expansion of the Canadian role in Iraq by saying allied local fighters “have neither the tools nor the training whatsoever to be able to do this.”

Brig.-Gen. Rouleau also announced that, for the first time, Canadian military advisers have engaged in a firefight with the enemy after coming under attack when they were at the front lines conducting training. He said Canadian troops are spending 20 per cent of their time near the front lines and the exchange of fire happened within “the last seven days.”

These revelations would appear to make it more challenging for the Harper government to say Canada does not have “boots on the ground” in Iraq, meaning soldiers engaged in direct combat with Islamic State jihadis.

Jack Harris, Official Opposition defence critic, said the military advisery mission is not unfolding as advertised.

“If we’re at the front lines and calling in air strikes and we’re engaged in firefights because we’re subject to machine-gun fire, that’s not what Canadians were told,” the New Democrat MP said.

The Harper government, which sent the soldiers to Iraq early last fall, said in a parliamentary motion that Canada would not “deploy troops in ground combat operations.”

The special forces assignment is largely training – helping Iraqi security forces become more proficient with marksmanship, battlefield medicine, sniper techniques, global positioning systems, mortars and defusing bombs.

Brig.-Gen. Rouleau played down the recent exchange of fire with militants, comparing it to Canadian peacekeepers defending themselves while serving in Bosnia in the 1990s.

He said the recent firefight took place when soldiers moved to the front line “to visualize what they had discussed over a map” with the peshmerga they were training. “They came under immediate and effective mortar and machine-gun fire,” he said, and Canadians responded with sniper fire, “neutralizing the mortar and the machine gun positions.”

The deployment is supposed to end by early April, and the Harper government will have to decide whether to extend the advisory role and the air combat mission.

Jason MacDonald, director of communications for the Prime Minister’s Office, said painting targets with lasers for air strikes is not the same as ground combat, and he pointed to Brig-Gen. Rouleau’s explanation.

The senior military officer said Canadian soldiers are merely making the air strikes more efficient. “We have the ability to help make the process involving the delivery of coalition aircraft kinetic effects better, safer, faster. We have those capabilities on the ground and so we’re assisting Iraqi security forces who own the combat mission” against Islamic State militants.

Roland Paris, director of the Centre for International Policy Studies at the University of Ottawa, said he considers what’s happening an escalation.

“Setting aside any legalistic discussion about what counts as combat, the implication previously was that we had one kind of mission and today it seems to be a different one.”

Philippe Lagassé, a military expert at the University of Ottawa, said he considers the actions to be within the parameters of the original mission.

“It ultimately comes down to impressions. I think it’s fair to say this is not the impression that was being given about what they were doing. That said, if you are going to get into the technicalities, they never said they weren’t going to do this.”

STEVEN CHASE

OTTAWA — The Globe and Mail

Published Monday, Jan. 19 2015, 3:18 PM EST

Last updated Monday, Jan. 19 2015, 9:16 PM EST