With the future of the North American free-trade agreement up in the air, Ottawa is scrambling to ensure that trade with the United States is not seriously disrupted.

U.S. trade is vital to Canada, and rewriting NAFTA could affect huge swaths of the country’s economy and labour market, as well as global supply chains.

How the decades-old free-trade deal with the U.S. and Mexico will change as the Trump administration pursues protectionist policies is still unknown. U.S. President Donald Trump believes revamping NAFTA, and U.S.-Mexico trading rules in particular, would revive factory jobs and bring manufacturers back to the U.S.

While Mr. Trump has singled out Mexico as a target he has so far taken a softer approach with Canada, saying it is a “much less severe situation than what’s taken place on the southern border,” and telling Prime Minister Justin Trudeau late February that he will only be “tweaking” NAFTA’s terms with Canada.

And it’s not just NAFTA that is in play. Mr. Trump’s administration says it could ignore rulings from the World Trade Organization, which resolves global trade rifts. And a tax on imports into the U.S. could also be implemented if top Republican lawmakers have their way.

Formal negotiations for a NAFTA overhaul have yet to begin and many political battles lie ahead. Mr. Trump’s views have shifted multiple times. Initially he said the border tax did not make sense, but recently told Reuters he supported a form of a border tax, which would place a levy on imports, but not on exports.”What is going to happen is companies are going to come back here, they’re going to build their factories and they’re going to create a lot of jobs and there’s no tax.”

Canada is expected to notch up its third consecutive month of trade surpluses when January’s numbers are released on Tuesday – the country’s first signs of positive trading since oil prices collapsed mid-2014.

Here is a look at what’s at stake.

The U.S. dwarfs all of Canada’s other trading partners, with three-quarters of our exports flowing south of the border. Canada’s second-largest trading partner, the European Union, accounts for less than 10 per cent of our exports and so although a free trade deal with the EU was recently ratified, European countries can’t replace the U.S. market.

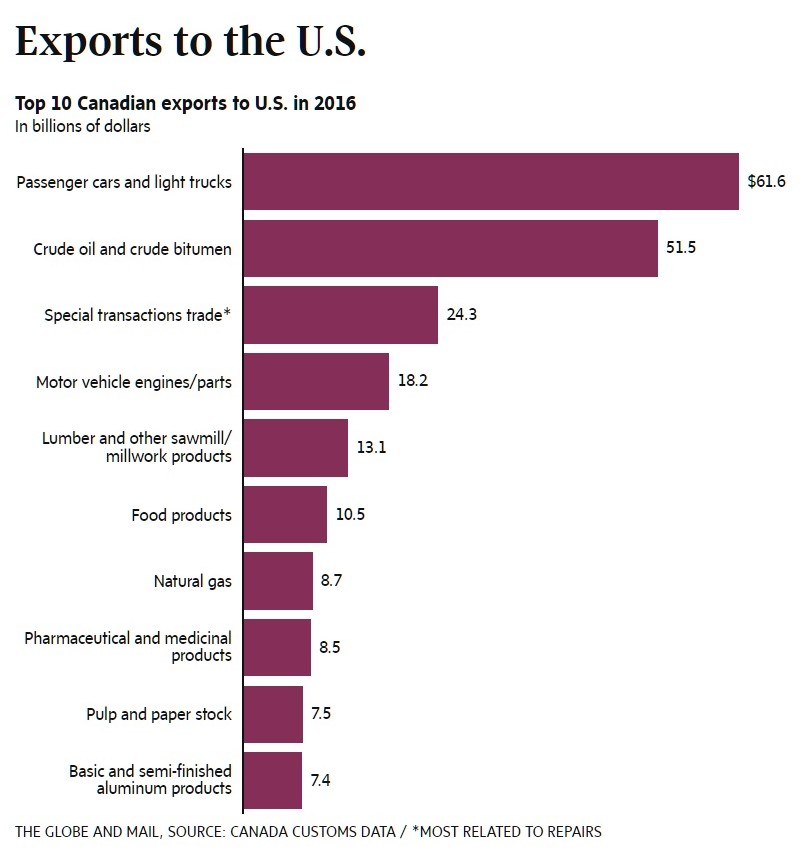

Vehicles, crude oil and auto parts account for a third of our total exports to the U.S. Cars, light trucks and auto parts exports were worth a whopping $79.8-billion last year, while crude oil and bitumen were valued at $51.5-billion, according to Canadian customs data.

These products are also integral to global supply chains. The auto industry was built around NAFTA, with manufacturers, suppliers, producers and retailers scattered across the continent.

The trade deal allows auto parts to travel easily around North America, with some products crossing the Canadian, U.S., Mexican borders multiple times before being assembled into a vehicle. That means any tweaks to NAFTA could slow production, increase costs and ultimately make vehicles more expensive for consumers.

Other top exports include lumber, natural gas, aluminum and pharmaceutical and food products.

They need us almost as much as we need them: Canada is the U.S.’s second-largest trading partner after China, sending $278-billion worth of exports north of the border. It is the No. 1 market for 35 states, with some regions moving as much as two-thirds of their exports our way.

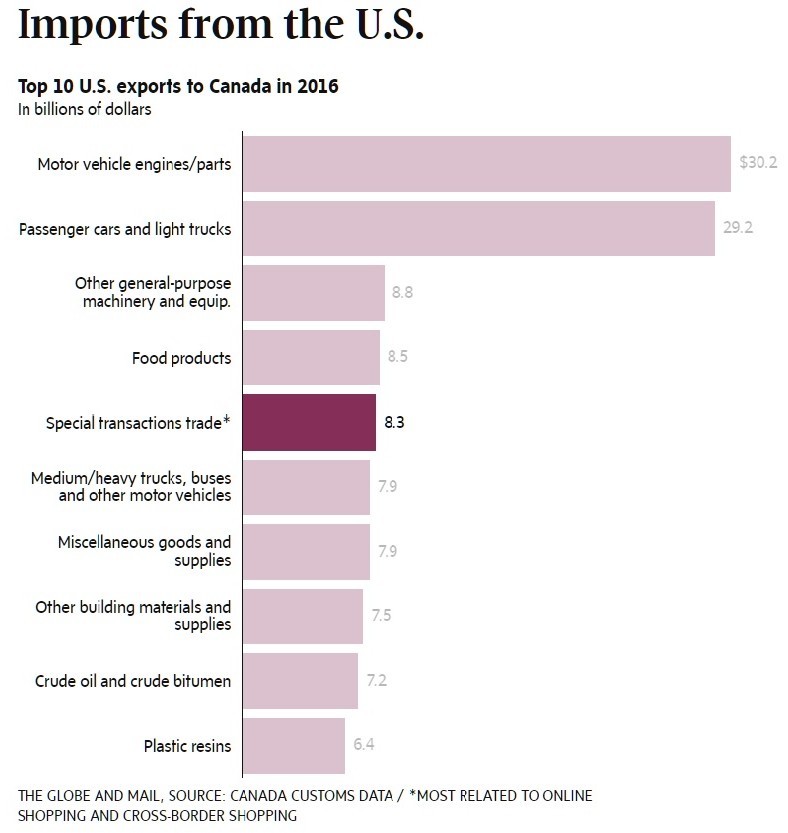

Like Canada, vehicles and auto parts are top U.S. exports. Canada has also become the top destination for American crude oil. The U.S. now sends upwards of 400 million barrels of crude oil and bitumen to refineries in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador, compared with about 50 million five years ago.

Even if the U.S. maintains free trade with Canada and imposes tariffs on Mexican products, the new relationship would still hurt Canada’s economy. Mr. Trump’s threat of a 35-per-cent tariff on Mexican vehicles would increase costs and hurt Canadian businesses with Mexican subsidiaries. Some of these Canadian auto manufacturers and producers have already seen business wane. The drop in the peso and fear of U.S. protectionist measures have slowed investment in Mexico, companies say.

Canada’s manufacturing and natural resources sectors stand to lose the most if a border tax is imposed or if NAFTA is repealed.

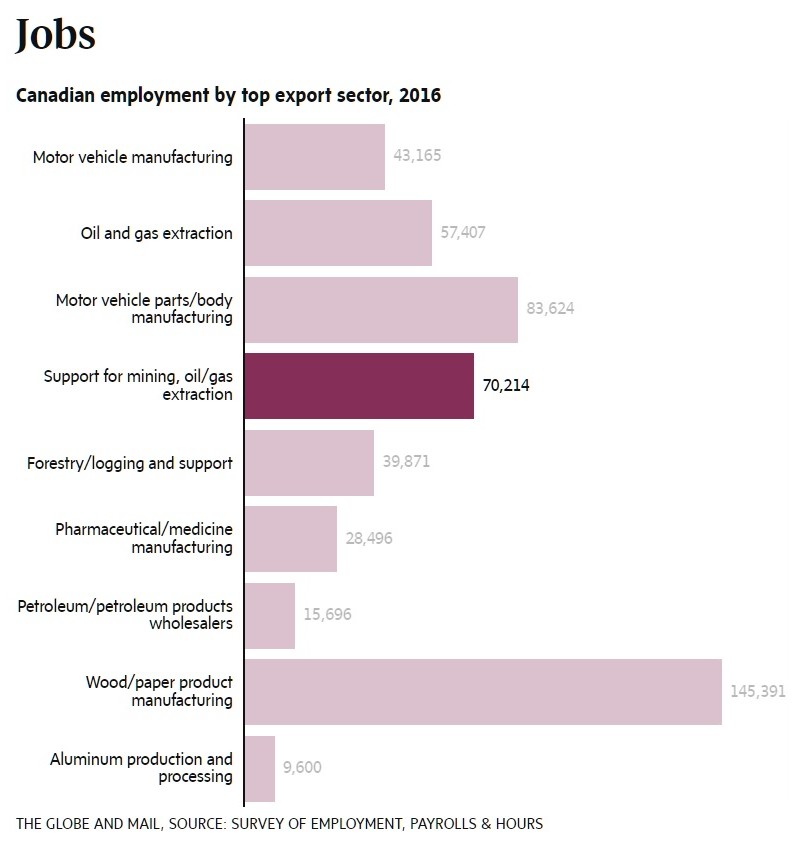

Last year, oil extraction, as well as wood and paper products manufacturing, had the largest work forces, while auto makers and their suppliers employed 115,000, according to Statistics Canada.

Factory jobs have been steadily declining since NAFTA was implemented in 1994. Over the past two decades, the manufacturing sector has eliminated more than 300,000 positions, many of which were lost during the Great Recession.

That sector has yet to rebound even with a faltering Canadian dollar, and now accounts for less than 10 per cent of the labour market, compared with 15 per cent in the early 1990s.

Although goods-producing jobs are a small portion of the country’s labour market, there are thousands of positions related to servicing the auto and natural resources industries.

“When we ship autos to the U.S., there are lots of Canadian service jobs embodied in the car. Transport, retail, storage,” said Isaac Holloway, assistant professor of business at Western University’s Ivey Business School.

RACHELLE YOUNGLAI

ECONOMICS REPORTER

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

LAST UPDATED: MONDAY, MAR. 06, 2017 5:56PM EST