Violent conflicts and threats to the territorial integrity of some of the world’s most vulnerable countries are among the more ominous risks posed by an ever-warming planet, according to the UN organization given the task of assessing the impacts of climate change.

In a report that for the first time includes human security in its review of how global warming will be experienced around the world, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) lists outcomes such as the displacement of populations, food shortages and economic shocks that are triggered or exacerbated by rising temperatures.

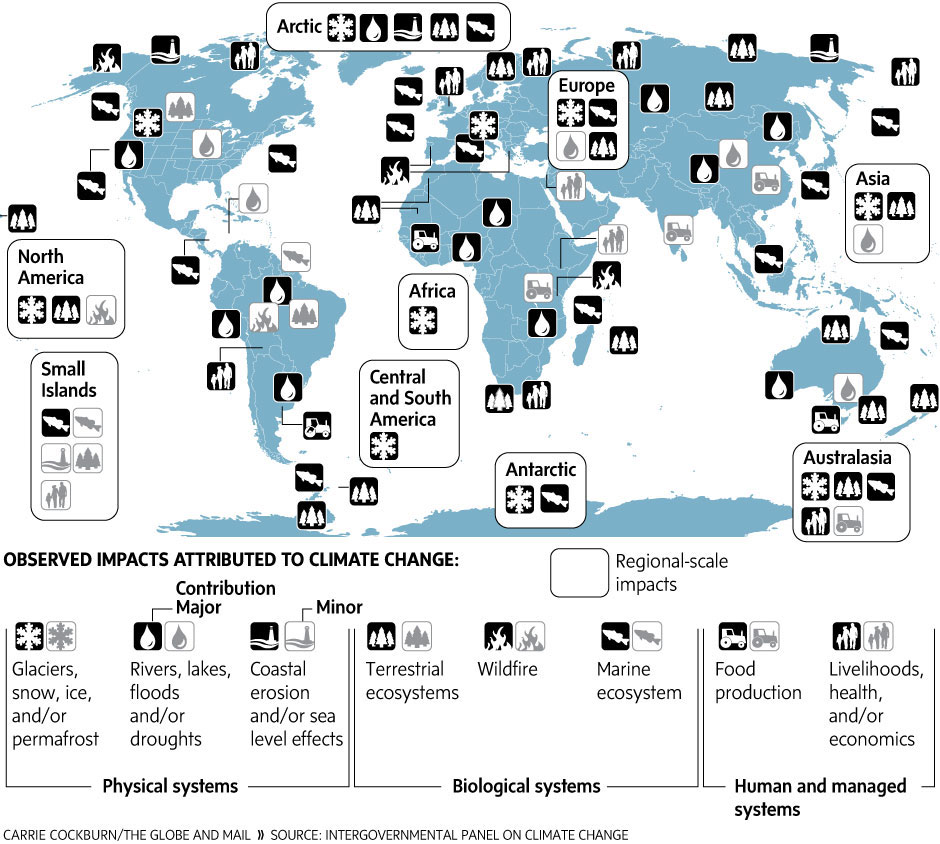

INFOGRAPHIC

Detailing the impact of climate change on a global scale

A new report from the IPCC sets out the risks, from insecurity over food supplies to violent international conflicts over access to water.

A new report from the IPCC sets out the risks, from insecurity over food supplies to violent international conflicts over access to water.

“If the world doesn’t do anything about mitigating the emissions of greenhouse gases and the extent of climate change continues to increase, then the very social stability of human systems could be at stake,” said Rajendra Pachauri, chairman of the IPCC, at a news briefing in Yokohama, Japan, where the report was released.

And while the impacts are poised to hit the world’s poorest most severely, climate change is already affecting lives in every region of the globe, the report finds. “Wealth is not protection from vulnerability, but what you see is exposure and vulnerability unfolding in different ways in different societies,” said Christopher Field, a professor of global ecology at Stanford University and co-chair of the working group that produced the report, which synthesizes the work of hundreds of researchers.

So far, among the most obvious impacts experienced by city dwellers in North America are meteorological, including a higher risk of dangerously extreme heat in summer, heavier precipitation and flooding events and a decreasing snowpack in winter months.

“We are very confident that our weather has begun to change and that adaptation to that change has started,” said Paul Kovacs, executive director of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction, based in Toronto and London, Ont. “Much of the adaptation has been reactive, particularly after extreme weather events.”

Dr. Kovacs was one of the lead authors involved in crafting the North America chapter of the report and among the dozens of Canadian researchers who contributed to the document overall.

Larger consequences for North America are in store, including the loss of glaciers in the West, with implications for water supplies, threats to the livelihood of northern communities because of vanishing sea ice in the Arctic and impacts on coastal industries because of shifts in populations of economically important fish species.

The report, the second part of a larger IPCC assessment, presents the consequences and risks of a changing climate at a far greater level of detail and with more confidence than in the previous UN assessment, seven years ago.

That document drew harsh criticism when one of its predictions – that the Himalayan glaciers would vanish by 2035 – was found to be without scientific basis. The aftermath of the controversy led the IPCC to enlist a broader pool of authors and a more rigorous system of review for the latest assessment.

Despite these changes, the new report is certain to inflame critics of the IPCC who say the climate threat is overblown and that the economic costs of curtailing fossil-fuel use to reduce emissions is too great. Researchers looking at the long-term trends counter that the problem is more like that of a large ship on a collision course.

“It really comes down to risk management,” said John Stone, an adjunct professor at Carleton University and a lead author of the chapter dealing with the polar regions. “The longer we put off action, the riskier it’s going to become and the more expensive it’s going to become.”

IVAN SEMENIUK – SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Sunday, Mar. 30 2014, 10:53 PM EDT

Last updated Sunday, Mar. 30 2014, 10:59 PM EDT