As the federal government prepares to roll out climate-related spending commitments as part of its economic recovery strategy, a report being released on Tuesday suggests that Canada’s emissions reductions targets could be achieved at a surprisingly manageable cost.

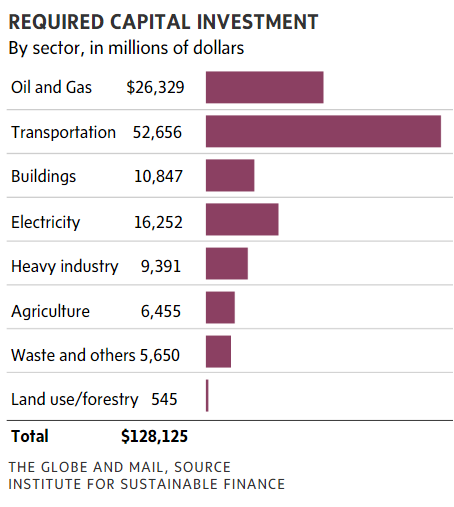

Produced by the new Institute for Sustainable Finance at Queen’s University, the study estimates that meeting the country’s Paris Agreement targets requires a total capital investment of approximately $128-billion over the next decade, with a range of $90-billion to $166-billion, depending on technology and other variables. And the study predicts at least half of that could come from the private sector, particularly if the federal Infrastructure Bank and other mechanisms are used to help build public-private collaboration.

The share coming from governments would still require more spending on climate-change mitigation than Canada has seen to date – all the more so if Justin Trudeau’s Liberals maintain a recent promise to exceed rather than just meet the Paris targets. But it could still be a relative pittance compared with the totals being spent in a shorter time frame to fight the health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

Ryan Riordan, the report’s co-author, said that the estimate – based on a calculation that Canada needs to cumulatively reduce emissions by 789 million tonnes over the next 10 years to meet its 2030 commitments, and on available data about abatement costs in various sectors – was lower than he expected going in. “If there’s one message that I think we get out of the whole report, it’s that it’s very doable,” Dr. Riordan said.

Queen’s University chancellor Jim Leech, who serves on the Institute’s advisory committee, said that he, too, was surprised. Mr. Leech suggested the report may help remedy an “uninformed dialogue” dominated to date by hard-liners on both sides: opponents of ambitious climate-change policy who argue it’s too expensive, and climate advocates “not really being specific about numbers, just sort of waving their hands.”

But as encouraging as the top-line cost number might be, the report’s breakdown of projected emissions-reduction costs by sector – and especially by province – also give cause to expect further fractious debate.

The “lowest hanging fruit,” the report’s authors write, is in the buildings sector, which currently represents about 11 per cent of national emissions. They suggest that a nudge from government – which Mr. Trudeau’s Liberals seem to be planning, through incentives to retrofit homes and commercial buildings – would unlock a great deal of capital toward energy-efficiency improvements.

More daunting is the transportation sector, which accounts for 24 per cent of national emissions (as of 2018), but more than 40 per cent of projected abatement costs over the next decade. That disproportionately high cost is largely owing to “vast amounts of locked-in capital and established networks built for carbon intensive vehicles.” Combined with a high degree of uncertainty around the evolution of vehicle electrification and other technology, that suggests a difficult path for governments in trying to efficiently decarbonize passenger and commercial transport.

But the biggest red flag in the report will come as little surprise to anyone familiar with Canada’s climate debates: the disproportionate burden to be carried by provinces home to an oil and gas sector that is the biggest national source of emissions.

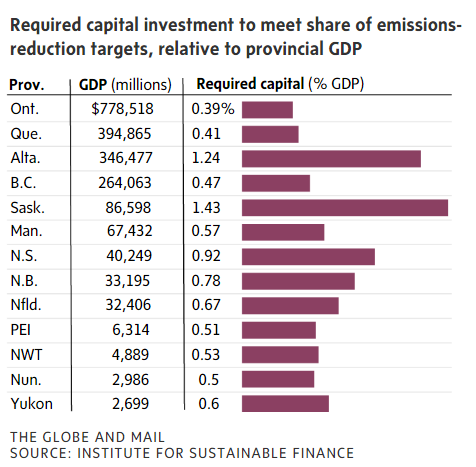

The per-unit cost of abating fossil-fuel emissions in the sector is lower than in some others, with relatively cheap opportunities such as methane reduction helping keep the necessary capital injection below that of transportation. But geographic concentration means that Alberta requires an estimated $43-billion of total emissions-reduction investment over the next decade. That’s by far the highest of any province, with Ontario next at about $30.5-billion.

Saskatchewan is in a similar boat. Its required total emissions-reduction investment is projected at $12.4-billion, roughly the same as British Columbia, a province with more than four times its population. So Saskatchewan’s total would represent the highest share of GDP for any province.

Such projections are liable to draw protest from Saskatchewan and Alberta, which are already complaining about bearing a heavy burden from the federal climate agenda. But Mr. Leech suggested the numbers may help the rest of the country understand such concerns. “I think it’s important to quantify it regionally, so everyone gets the full picture,” he said.

Dr. Riordan, meanwhile, said that despite the projected costs facing oil and gas provinces being high compared with other jurisdictions, they’re still lower than might have been expected – and very attainable considering rapid technological advances in the resource sector, and the amount of private capital that usually flows into it.

For oil and gas and every other sector, the report says in its conclusion, a sense of urgency will help limit the total costs of meeting the targets, while presenting more opportunities to compete in a decarbonizing world. If governments and the private sector wait too long, however, available options will diminish and more restrictive regulations may be needed.

It remains to be seen whether Mr. Trudeau’s government, which promised in last week’s Speech from the Throne to “immediately” bring forward a plan to best its 2030 commitments, will detail year-by-year or sectoral paths for getting there. But that rollout has gotten a setup from the new think tank that is unexpectedly optimistic, even if not every corner of the country will see it that way.

ADAM RADWANSKI

The Globe and Mail, September 29, 2020