Nipissing University must consider cutting courses and faculty, selling off real estate assets and improving its financial controls and processes if it wants to survive in the face of declining enrolment and revenue, says an independent auditor report commissioned by the Ontario government.

The 100-page report by PricewaterhouseCoopers was completed as part of discussions on how to help the school deal with the impact of changes to teacher-education programs across the province. Faculty at the university oppose many of the recommendations, which could see entire departments eliminated and increased teaching duties for many professors.

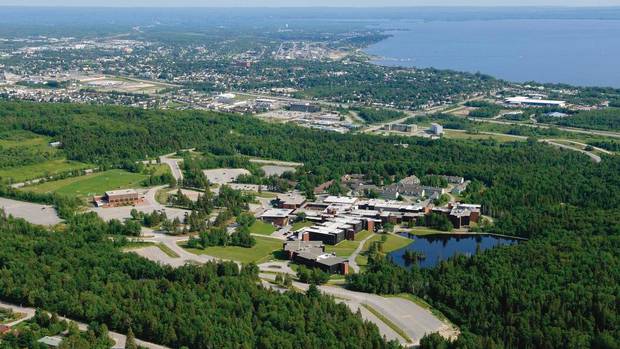

Michael DeGagné, the school’s president, said the North Bay university will begin holding town halls on the report later this winter.

“It’s not a blueprint for our future action. It’s a list of suggestions on how we might be able to make changes in our institution and make changes to our sustainability efforts,” he said.

The audit, however, states that if Nipissing can’t grow its revenue and find cost savings, it will face a $24-million deficit by the 2019 academic year, almost a third of its annual revenue. About 50 non-academic staff were laid off last year, but that’s far from enough, according to the report.

“Current strategies and practices will not get the university to achieve a sustainable financial position – in fact, not going beyond announced strategies is financially unsustainable,” PwC says in the report, which was obtained by The Globe and Mail.

Non-essential courses that are losing money should be eliminated, it says. The report names six departments in particular: chemistry, computer science, fine arts, history, political science and arts and cultural studies.

While the challenges faced by the 5,000-student institution are acute, they are shared by other Ontario universities outside the Greater Toronto Area. Other universities, such as Laurentian and Windsor, have also seen the number of applications from high school students decline.

Most of the province’s grants to universities are based on enrolment and have grown as school participation has gone up over the past decade and a half. Now, as the university-aged population declines, the province is discussing changing its funding formula partly to ensure institutions are sustainable.

For smaller communities outside the GTA, where postsecondary institutions are key employers, the loss of middle-class jobs hits particularly hard, Dr. DeGagné said.

“For a large university in a more dense area, the university has great importance. But it may not have the same importance the university has to North Bay – depending on how you count, we would be in the top three employers here,” he said.

Nipissing’s external challenges are compounded by severe internal problems, the PwC report states.

Governance and financial accountability and strategy are rated at the poor end of a best-practices scale, for example. When the report was written, the university was even operating without a chief financial officer, but someone has since been appointed to take over those duties.

The faculty association questions the entire report and the projected budgets on which it was based. Deficits have been overstated for several years, it says.

“The budget is always a political document,” said Susan Srigley, president of the Nipissing University Faculty Association (NUFA).

This past fall, professors were on strike for much of November, deepening existing tensions between academics and administrators.

While the university announced in June that it would close its Bracebridge, Ont., campus and sell the buildings – one of the recommendations also made in the PwC report – NUFA would like that decision reopened. Representatives from Bracebridge City Council attended a meeting of the school’s board of governors on Thursday.

“The decision to close the Bracebridge campus happened very quickly and the board was not given sufficent info,” said Hilary Earl, an English professor and a member of the NUFA executive.

Some of the budget issues the school is facing have been caused by changes to teacher education programs implemented by the province in 2013. The changes had the net effect of reducing funding to education faculties by a third. The province is providing funding to tide schools over the transition from a one-year to a two-year bachelor of education program, a government spokesperson said.

SIMONA CHIOSE – EDUCATION REPORTER

The Globe and Mail

Published Monday, Feb. 08, 2016 9:34PM EST

Last updated Monday, Feb. 08, 2016 9:34PM EST