The number of children worldwide who are obese has grown by more than 10 times over the past 40 years and will outnumber those who are underweight by 2022 if current trends continue, a new study from the World Health Organization says.

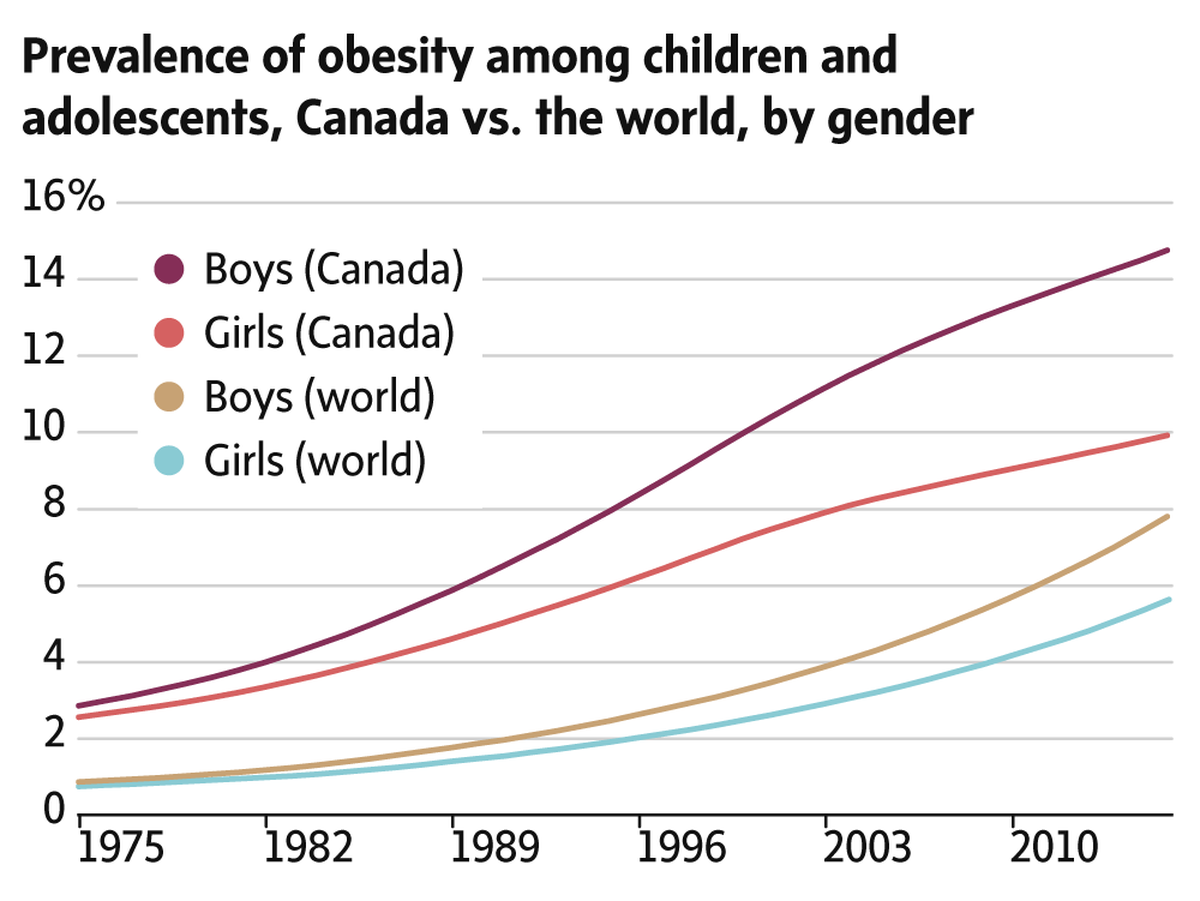

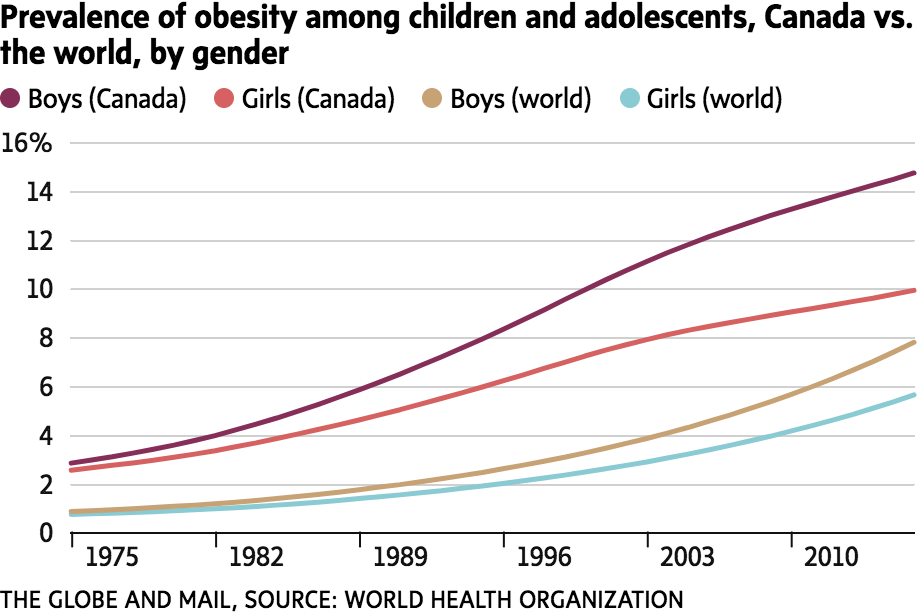

And while the trend is showing some signs of abating in wealthy regions like Canada and the United States, experts say that could be temporary, because the underlying factors driving the crisis have not changed.

“It would appear for the moment that we are cresting – at least that would be my take on it,” said Yoni Freedhoff, medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute in Ottawa and an obesity expert.

In Canada last year, the obesity rate for girls was 9.9 per cent – the tiny island country of Nauru, at 33.4 per cent, had the highest rate for girls – and 14.7 per cent for boys, compared to the Cook Islands, where the rate was 33.3 per cent for boys.

Among high-income countries, the United States had the highest obesity rates for girls, at 19.5 per cent, and boys, at 23.3 per cent.

The study said the number of obese children and adolescents – aged five to 19 – rose from 11 million in 1975 to 124 million in 2016. If the rate of increase does not change, more children and adolescents will be obese than moderately or severely underweight by 2022.

Dr. Freedhoff and other experts say there are significant gaps in treatment and research, which makes reducing the obesity rate difficult. Dr. Freedhoff said parents or individuals have been left to deal with the problem, and that is not having the impact needed.

“It’s not as if parents and people weren’t aware of the issue or concerned about it before,” he said.

“It’s that those sorts of approaches are useful for a very small sliver of the population … It’s like swimming against a torrential current. It doesn’t matter how motivated a parent or a child might be, if the world is constantly thrusting crap into their hands and mouths – which to some extent, it almost literally is – we don’t stand a chance.”

“Although there are some positive signs, the overall picture is grim,” James Johnson, a professor of cellular and physiological sciences and surgery at the University of British Columbia, said in an e-mail.

“Childhood obesity continues to represent a major health crisis and a ticking time bomb for future health problems including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer,” he added. “In all of these diseases, the effects of obesity accumulate over many years and we may not know the full extent of the health burden brought about by today’s obesity for decades.”

While some regional and socioeconomic groups are seeing a plateau of childhood obesity rates, those levels are still dangerous, and “the situation continues to get worse in vulnerable populations and those without food security, including First Nations people,” Prof. Johnson added.

And while the apparent plateau in childhood obesity rates in some countries may be a positive trend, other numbers – including a steep rise in the number of people with severe obesity – reflect a problem that is far from being under control, said Arya Sharma, scientific director of the Canadian Obesity Network.

The network has flagged the lack of treatment for people with obesity and a patchwork of systems that do not necessarily help people who need it, including parents who may be seeking advice for their children.

“As much as we should be concerned about stopping this [obesity] in the first place, particularly in children, we aren’t doing enough for people who already have this problem – and we are talking about over seven million Canadians who already have this chronic disease who essentially don’t get treatment,” Dr. Sharma said.

Those people may be getting treatment for obesity-related conditions, such as sleep apnea or heart disease, but not for obesity itself, he added.

For parents who may be worried about their children’s weight, Dr. Freedhoff suggested taking an approach that doesn’t shame children, while cutting out “low-hanging fruit,” such as sugary drinks and restaurant meals.

“If a parent out there is worried about their child, who’s quite young, about their weight, please don’t put the weight of that condition on that child’s shoulders,” Dr. Freedhoff said. “If there’s a concern, then it is within a parent’s control to help – but children don’t have concern over their environments the way their parents do. So why involve them if they are not in charge?”

Globally, obesity rates climbed from less than 1 per cent of girls and boys in 1975 to nearly 6 per cent of girls and nearly 8 per cent in boys last year, the study said.

The study was based on comparisons of body mass index, a measurement of a person’s weight and body fat mass compared with their height.

In a statement, lead study author Majid Ezzati, a professor of global environmental health at Imperial College London, said the trends reflect “the impact of food marketing and policies across the globe, with healthy nutritious foods too expensive for poor families and communities.”

WENDY STUECK

The Globe and Mail, October 11, 2017