Ontario’s two million public school students will learn remotely for the last four weeks of the academic year as the government looks to keep its large-scale reopening plans for the summer on track, rather than have children return to the classroom.

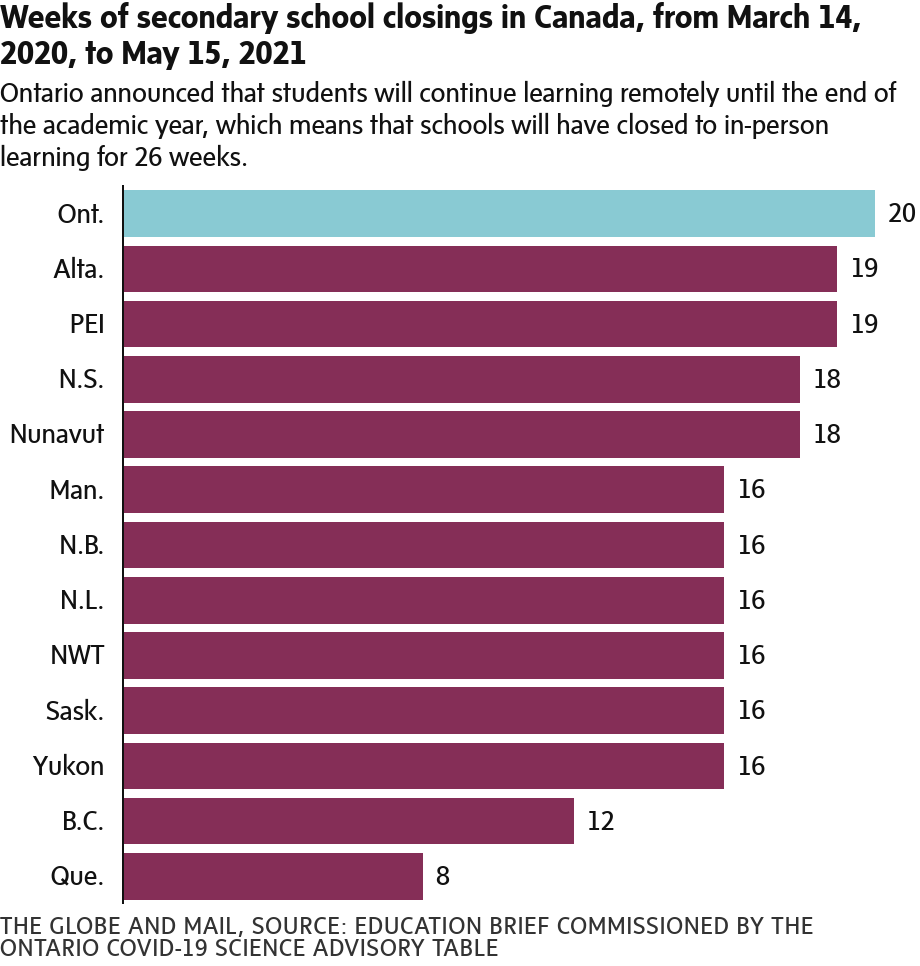

Schools in the province have been closed to in-person learning for 23 weeks so far, since the spring shutdown last March, longer than anywhere else in Canada. In comparison, schools have been closed for 12 weeks in British Columbia and eight weeks in Quebec, according to an education brief commissioned by Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table that looked at school closures between March, 2020 and May 15, 2021.

Premier Doug Ford said on Wednesday that he did not want to “take unnecessary risks with our children right now,” despite his government repeatedly stating that schools were safe. He was adamant that he was not prioritizing the economy over children and stated he was “hopeful” Ontario would be able to move into the first step of its reopening plan sooner than June 14.

The announcement to have students continue learning remotely was made despite a general consensus from the medical community and educators that children should return to the classroom for June, albeit in regions where COVID-19 infections are low. Educators and medical experts are increasingly worried about the mental health and well-being of children, not to mention the learning gaps that are associated with school closures. The government closed all schools to in-person learning in mid-April because of a sharp rise in COVID-19 infections (schools in Thunder Bay and Sudbury had been closed since March).

“Ontario kids have been out of school longer than children almost anywhere else in the world. I am overwhelmed by sadness about all this. It feels like we adults have let our children down,” Alex Munter, the head of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, said over social media. He added that children have made “enormous sacrifices in the fight against COVID,” and that the government needs to plan for an uninterrupted academic year to address mental health and learning losses.

However, the move to keep schools shuttered until September was supported by others, including the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, which said the risk of a fourth wave is too high.

Elsewhere in the country, students in Nova Scotia will return to school this week despite the government saying last month that students would learn remotely for the remainder of the academic year. Several areas of Manitoba, including Winnipeg, have moved students to remote learning because of rising COVID-19 infections.

The role that schools play in the transmission of the virus remains an evolving picture. However, an education brief commissioned by Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table and released on Wednesday found that school closures have “multidimensional consequences” on children, including on their mental and physical health. “Closures have immediate and future economic costs, with modelling data suggesting an impact on future lifetime earnings, as well as depressed labour force participation for parents, particularly mothers,” it stated.

Tess Clifford, the director of the psychology clinic at Queen’s University in Kingston and a parent, was disappointed to hear the government was keeping schools closed. Many children, she said, can’t participate in summer camps and outdoor sports, “and we need to hear what the government will be doing to support those children and families.”

“We need to hear a clear plan toward recovery for children and youth, which includes a commitment to have a regular school year next year. Kids and families need to know they can count on their leaders to prioritize kids well-being,” Dr. Clifford said.

NDP education critic Marit Stiles said the Premier “had given up on our kids.”

“He had a choice to invest in keeping them safe and putting the needs of our children first and he made the wrong choices.”

While COVID-19 case numbers and hospitalizations have been dropping in Ontario, intensive-care units still have a higher number of patients than they did at the peak of the second wave in January, with 573 people in ICUs, as of Wednesday with illness related to COVID-19.

The government is reviewing data to determine whether the province can enter the first step of its reopening plan, which includes allowing patios and retail capped at 15-per-cent capacity, before the anticipated date of June 14. Mr. Ford said he was awaiting guidance on the matter from outgoing Chief Medical Officer of Health David Williams, who is looking at data from the May long weekend.

Mr. Ford said on Wednesday that although schools are closed to in-person learning, his government would allow outdoor graduation ceremonies. It is unclear how that would happen under current restrictions that limit gatherings, and many schools have been tirelessly working on virtual ceremonies.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced Wednesday that the province’s students won’t be returning to in-person learning for the remainder of the school year. Ford defended the decision when pressed by reporters, saying the large number of students, the spread of COVID-19 variants and loose border controls were key factors. THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The government will work with public health officials and school boards on how to proceed, the Premier’s office said. The first step of the province’s reopening plan limits outdoor gatherings to 10 people, but for outdoor ceremonies, the capacity is limited to the number of people who can attend while maintaining physical distancing of two metres.

CAROLINE ALPHONSO, EDUCATION REPORTER

LAURA STONE, QUEEN’S PARK REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, June 2, 2021