Ketty Nivyabandi, a refugee who was once homeless in this country, has become the first female Secretary-General of Amnesty International Canada.

Only five years ago, Ms. Nivyabandi fled Burundi amid political unrest and a violent government crackdown on protests, some she helped organize. She had packed a small bag, thinking she and her two daughters might be gone for a few days, possibly longer – she has not returned. Ms. Nivyabandi joined her sister in Calgary, and was granted refugee status, an emotional process that left her feeling as though she was surrendering her identity.

In her new position at Amnesty International Canada, the 42-year-old Ms. Nivyabandi said she will continue to advocate for the rights of Burundi people, but has many priorities, including Canadian human-rights violations at home and abroad.

One priority, she said, is examining Canadian businesses that, through their work abroad, effectively support regimes that are abusing human rights, such as the shipping of military goods to Saudi Arabia.

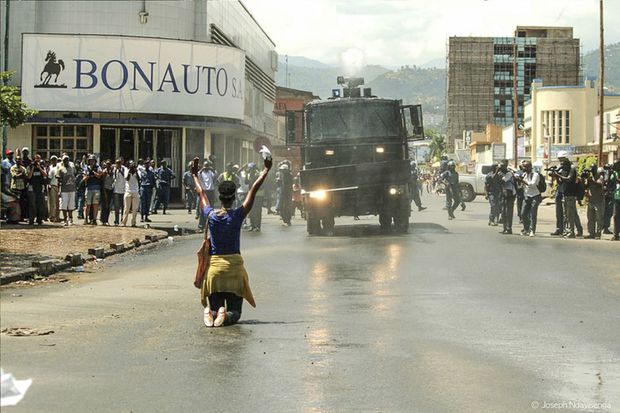

Ms. Nivyabandi kneels in peaceful protest before a police water cannon used to disperse the women’s march in Burundi in May, 2015. COURTESY OF FAMILY

Ms. Nivyabandi said she will also focus on anti-Black racism and discrimination against Indigenous people in Canada. She said her organization has called for a ban on racialized police profiling, for example, and wants to see the Canadian government take action to dismantle white supremacist groups. She would also like to see a bill on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed into federal law.

Ms. Nivyabandi said she had a personal experience with discrimination in Canada while trying to find a job when she moved to Ottawa in 2016. She said despite applying for positions she was qualified for, she wasn’t getting called back because they required Canadian job experience.

“We were homeless for awhile and lived in a shelter for awhile – that exposed me to the reality of refugees, or people who come to Canada – what they go through,” she said, adding newcomers are told they will not be able to hold the same profession they did in their home country. At the same time, she said, she met amazing people who helped welcome them.

“So to be a first-generation refugee and, five years into this, be in a position where I can make powerful decisions is a powerful message for others and I hope it tells any refugee and immigrant, especially girls, that you matter and your voice counts.”

Ms. Nivyabandi’s first job in Ottawa was teaching French to government employees, while advocating for Burundi issues and attending events on Parliament Hill. She later became the advocacy and research manager at Nobel Women’s Initiative.

Born in Belgium, Ms. Nivyabandi moved to her family’s home country of Burundi when she was five years old. She left at the start of the civil war in 1993, returning 10 years later to work as a journalist. She worked briefly in Uganda with the UN Development Program and returned to Burundi.

In the spring of 2015, Burundi was emerging from a long civil war when then-president Pierre Nkurunziza said he was seeking a third term in office, rocking that glimpse of peace, Ms. Nivyabandi said. The protests were non-violent, but police responded with force, killing a teen boy on the first day people took to the streets.

She had felt compelled to act after seeing it was mostly young men protesting and helped mobilize all-female protests, marching through the city of Bujumbura.

She remembers kneeling in front of a water cannon after hours of being teargassed.

“I just had to hold the hands of the other women we were with and make a decision to continue, despite the threat, which I think sums up what human-rights defenders always do,” she said.

When she’s not working, Ms. Nivyabandi unwinds by writing poetry, primarily in French, and has had her work published in international anthologies.

“When you’re doing human-rights work, you see human beings and governments at their worst, and it’s very easy to get discouraged and impacted by that. Poetry is the space that allows me to see beyond that, allows me to see the potential and to see what we could be. And that is what fuels me.”