A sweeping survey of traditional knowledge from the Mackenzie basin reveals Canada’s largest watershed in the midst of a rapid and uncertain transformation, Ivan Semeniuk reports.

At 71, Leon Andrew still travels and fishes on the vast and vital river he has known since he was a child.

“I’ve had a good life,” said the Mountain Dene elder from Norman Wells, NWT, located at the heart of the Mackenzie River basin. “I’ve had a lot of experience on the land.”

Over the years, that experience has made him an eyewitness to change. He has seen shifts in the types and health of fish species that are caught on the river and the lakes that feed into it. He has noted chronically low water levels that impede travel and has watched as slumping banks, weakened by melting permafrost, wash away. And, as with many other Indigenous people who live on the river and its many tributaries, he is concerned about concentrations of mercury and other contaminants from industrial activity under way all across Canada’s largest watershed.

Now, Mr. Andrew’s observations and recollections have become part of a comprehensive new report that marshals traditional knowledge from communities across the sprawling Mackenzie Basin. In the aggregate, those accounts offer a striking and consistent portrait of a riverine world in the throes of a sweeping transformation – a view that, until now, has been difficult for researchers to capture at the human scale.

“It’s not just ecological impact, but social, cultural and economic issues we’re identifying that a scientist wouldn’t necessarily see,” said Brenda Parlee, an associate professor in environmental sociology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton and co-editor of the report, entitled Tracking Change, which is set for release on Tuesday.

Dr. Parlee said the aim of the project is to enable communities throughout the Mackenzie basin to document and share their own knowledge about an aquatic ecosystem that they have long depended on for food and transportation. The conservation group WWF Canada, among others, has identified a deficiency in data on the Mackenzie when it come to species and habitats. With information patchy, the collective traditional knowledge acquired and passed down by Indigenous peoples offers an alternative picture of what is happening that is often more complete.

“We really don’t have a scientific record that rivals it,” Dr. Parlee said.

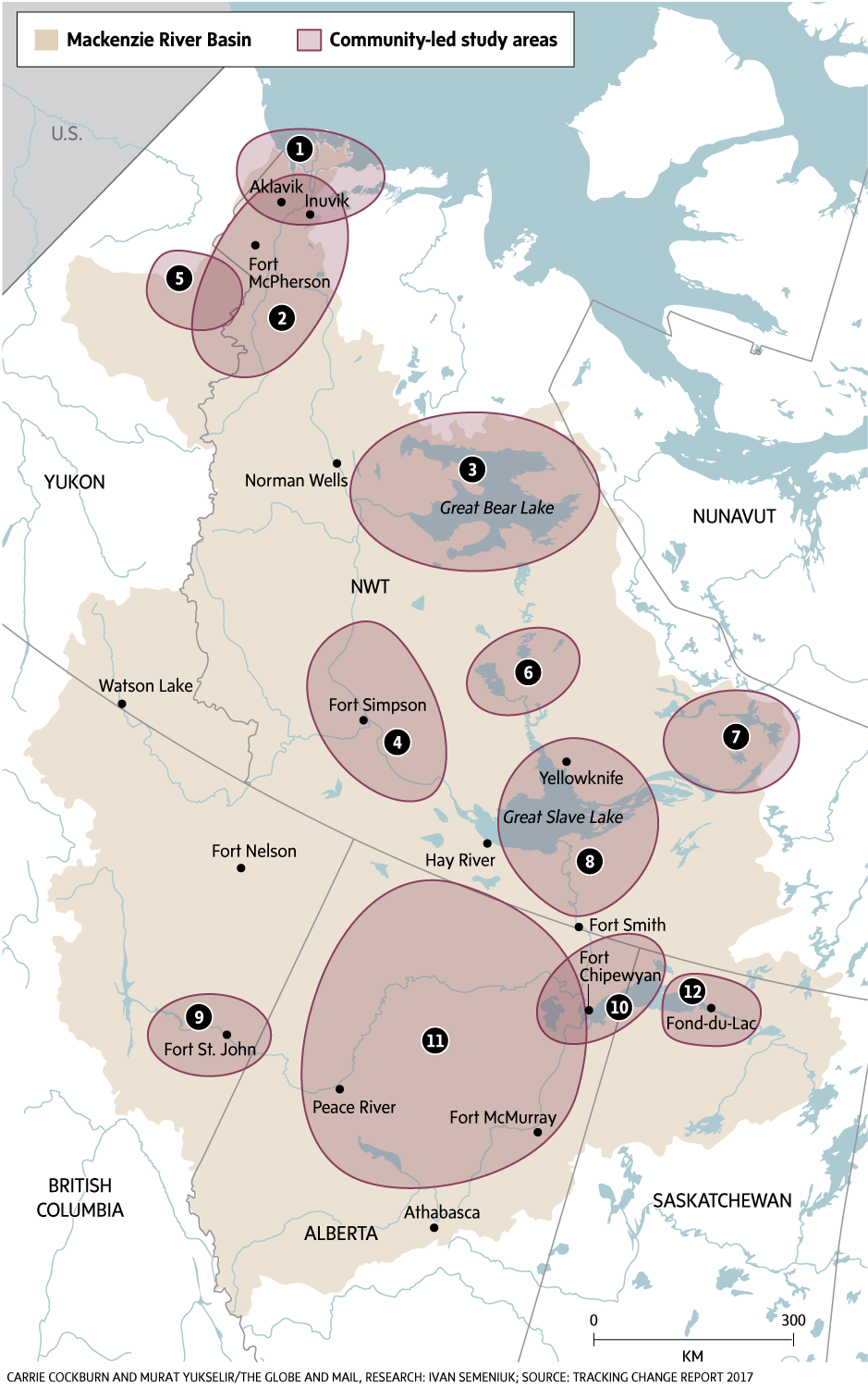

Bringing together the work of 12 separate Indigenous organizations from across the Mackenzie and its tributaries, the report documents impacts that are related to resource development, environmental contamination and the growing demand for hydroelectric energy in the basin’s headwaters. And while the various causes and effects are difficult to disentangle, the result makes clear how climate change acts as a multiplier by exacerbating the increasing pressure on a river system that drains one fifth of Canada’s total land area and helps sustain dozens of communities with tons of fish harvested annually.

“It’s a litany of woes that cumulatively are much worse than they are individually,” said John Smol, a biologist and environmental change researcher at Queen’s University in Kingston, who was not involved in the report. “Here we have another example of a major ecosystem that is under significant stress.”

Dr. Smol added that scientists don’t have the luxury to disregard the observations of northern peoples who are on the front line of climate change. “Who best to ground-truth what is happening than the people who are living there,” he said.

The federally funded report is part of a larger six-year research program that takes a global look at the role of local and traditional knowledge in informing watershed policies in three major river basins: the Mackenzie, the lower Mekong and the lower Amazon.

For the Mackenzie portion of the program, various community groups throughout the region were funded to take youth and elders out on the land to document knowledge about specific places and practices. Youth involvement was key for many of the participating groups who are also trying to develop their own community-based stewardship plans for the river.

“There was a ton of information shared,” said Dahti Tsetso, resource management co-ordinator for the Dehcho First Nations and a project lead covering the section of the Mackenzie that runs approximately from Great Slave Lake to Fort Simpson.

Ms. Tsetso said she was struck by the detail in the traditional knowledge gathered in her part of the study, including the changing water temperature and increasing cloudiness of the river due to silt, as well as the decline of the grayling, a once abundant species on the Mackenzie.

“There’s so much potential to grow that knowledge into more comprehensive research that would help inform the way we manage land and water,” she said.

Spanning three provinces and two territories, the waters of the Mackenzie Basin flow from as far south as Jasper National Park to the Arctic Ocean more than 4,200 kilometres away. The area encompasses some of the most contested environmental battlegrounds in Canada, from the Alberta oil sands and British Columbia’s proposed Site C dam to Yukon’s Peel River, where the Supreme Court is expected to rule soon on a landmark case over the territory’s plans for development.

The largest stakeholder, in terms of the number of communities that depend on the health of the basin, is the Northwest Territories, which is a partner in the Tracking Change project.

“We’re the ultimate downstream jurisdiction,” said Jennifer Fresque-Baxter, a watershed management adviser for the territorial government who added that one of the strengths of the project has been its emphasis on gathering and preserving knowledge that is meaningful to the people who live there.

“We’re really seeing a shift toward communities identifying the questions that they want to answer and pushing that forward,” she said.

The project demonstrates the increasing presence of traditional knowledge in discussions related to environmental research and planning in the North.

Henry Huntington, an Alaska-based researcher and consultant who advised the project said part of the report’s value lies in the way it reveals effects that would not be apparent or predictable from a more regional view of climate change.

While there’s no doubt that the sub-Arctic is feeling the effects of a warming planet, what is far less clear is how those effects and their ramifications are being felt through a multitude of unexpected shifts in the interlocking life cycles of plants and animals.

“To me that’s the fascinating part,” he said. “To see what things emerge that seem like natural and obvious connections to local residents but that never would have occurred to someone like me.”

What is less certain is how the newly documented traditional knowledge will be used to inform policy, particularly in the southern part of the basin where pressure on the aquatic environment remains greatest and where, as the report points out, traditional knowledge does not play a significant role in fish management.

Nowhere is this disconnect more evident than in the Peace-Athabasca Delta in Alberta, which is affected by water withdrawals for the oil sands and by hydro projects upstream. Reduced water flow exacerbated by climate change has meant that the delta, a vast freshwater wetland, is less able to recharge during the spring runoff. Two years ago the situation became so severe that the harbour in nearby Fort Chipewyan ran dry, cutting off local access to fishing areas.

“We’re not convinced those impacts are being assessed properly,” said Melody Lepine, a project leader for the Mikisew Cree First Nation contribution to the report.

The Mikisew Cree have practised community-based water monitoring for the past eight years in response to what communities see as inadequate efforts to do so by the federal and provincial governments. One benefit of being part of the larger report, she said, was sharing best practices for community monitoring across the Mackenzie basin.

“Our whole existence and cultural identity relies on our relationship to the land,” Ms. Lepine said. “If we don’t monitor those changes to the environment we won’t really understand how our culture and rights are being impacted.”

Common across the Basin:

In all the study areas, traditional knowledge suggests water levels are generally lower and warmer than in the past, while creeks and small rivers that feed into the basin are drying out. Lower water inhibits access to traditional fishing areas while the warming trend means that winter ice is often thinner and more treacherous.

North-south differences:

Major issues for Indigenous peoples in the north part of the Mackenzie watershed include melting permafrost and muddier water. Fish habitats are shifting and in some cases fish are smaller, fewer and in poor health. In the south, concerns centre on the cumulative effects of logging, mining, petroleum extraction and dams.

1. Mackenzie Delta

Changes witnessed by the Inuvialuit (western Inuit) in this area include the disappearance of some lakes as permafrost thaws and water is released and an increase in the number of beaver dams, which affect fish habitat.

2. Lower Mackenzie

Study area includes the Peel River, part of the Gwich’in settlement area. Changes include more sandbars, which impede travel, and willows growing along banks that were once open, blocking portage routes.

3. Great Bear Lake

Known as Sahtu to the Dene people of this region, the giant lake has seen the arrival of new species, such as char, which were not present before. Other concerns include contaminant releases from old mining sites.

4. Central Mackenzie

Members of the Dehcho First Nations have observed a drying-out of the landscape and an increase in landslides and floods of muddy water. Grayling, a once common fish species, have become less abundant.

5. Peel River Watershed

The Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation in this region have encountered higher variability in ice conditions and in river flooding with fish numbers in decline. Proposed hydro development is a major concern.

6. Tlicho Lands

North of Great Slave Lake, drier weather and warmer temperatures have brought forest fires of increasing scale and intensity, leaving substantial smoke and ash deposits on lakes and rivers.

7. Lockhart Watershed

Project participants with the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation report reduced rain and snowfall in their region and concerns over the impact of mining on groundwater and fish habitat.

8. Great Slave Lake

The Akaitcho region has witnessed changes in fish health attributed to past mining activity (including the former Giant Mine near Yellowknife) and shifts in fish species,including a rise in salmon occurrence.

9. Peace River, B.C.

Reports include changes in the health and abundance of fish linked to hydro development and recreational fishing and loss of access to fishing and sacred sites due to dams and other industrial activity.

10. Mikisew Cree lands

On the Peace-Athabasca river delta, low water and navigational hazards have reduced access to fishing. Changes include algal blooms fed by agricultural runoff and water quality issues related to oil-sands mining.

11. Peace River, Alta.

A Treaty 8 First Nations region that includes Lesser Slave Lake, where lake trout have been completely eradicated. Concerns include erosion due to clear cutting and water-flow issues associated with hydro.

12. Lake Athabasca

Recorded changes include reduced access to fishing in the lake and associated watershed due to the cumulative effects of logging, mining and other industrial development, with climate change a contributing factor.

IVAN SEMENIUK

Science Reporter

The Globe and Mail, October 9, 2017