Using code names such as Fox Hunt and Skynet, China has been urging its trade partners to extradite officials it believes are guilty of economic crimes. The effort is critical to the legitimacy of President Xi Jinping, who has promised to rein in the country’s pervasive graft issue, but critics also suspect it is part of his broader effort to purge enemies and consolidate power.

As The Globe and Mail revealed Tuesday, Canada and China are formally in discussions to complete an extradition treaty that would make Canada a signatory, joining Australia, France and other democracies. Compliance will likely have benefits: bolstering trade and furthering diplomacy.

“China likes to use trade to favour countries who are being nice to them, and when they are not nice, they are punished,” said Shaun Rein, founder of China Market Research Group. In that respect, he said, Ottawa is being savvy by engaging in discussions with Beijing. But many international law experts and diplomats warn that Fox Hunt is fraught with many tripwires, beginning with China’s opaque — if not brutal — legal system where the charges originate.

Here are seven things to know about Fox Hunt.

1) Canada has been identified as a major sanctuary for China’s top 100 economic fugitives

According to a report last year in the International Business Times, Canada has 26, second only to the United States, which has 40. New Zealand, which is third with 11, is also looking at signing up.

2) A political decision may still meet legal roadblocks

Last year New Zealand agreed to extradite a South Korean-born resident, Kyung Yup Kim, to China on murder charges. In July, however, its high court ruled that Beijing’s assurances of fair treatment for the suspect were inadequate, a potential sign that Chinese rule of law may not meet its legal standards, whether it involves murder or graft. In the meantime, Prime Minister John Key has said that his country would sign onto the treaty if it was for serious cases, and that the expatriates would not face torture or the death penalty.

3) Some Canadians might support the move

“Some Canadians might think, do we want these kinds of people living here?” said Mr. Rein, who is also author of The End of Cheap China. “A lot of these people are rotten.” Mr. Rein also suggested that the deal is not as one-sided as it seems. By signing a reciprocation deal, Canadian officials can better track who is living and working in Canada and not paying taxes.

4) Skynet is already well under way

France, which signed on last year, extradited a corruption suspect last week, following Italy and Spain, which have taken similar steps. Through new treaties or old-fashioned guile, China has been successful thus far in its repatriation efforts. In the first half of 2016, China brought over 381 fugitives, recovering illicit money worth more than 1.24-billion yuan (or $240-million), according to the Chinese media. According to the periodical Caixin, more than 40 per cent of the 738 fugitives who returned to China in 2015 were “persuaded” to come back rather than forcibly repatriated. “Family members sometimes played a role in these persuasion efforts,” a Shanghai police officer was quoted as saying. “It’s very effective. A suspect is like a kite. Although he is in a foreign country, his line is in China and we can find him through his relatives.”

5) Remember the term shuanggui

The word refers to double designation, in which corruption suspects must show up for interrogation at a designated time and place, as if such processes were so gentile. Instead they are likely to be whisked away to an unfathomable black hole of justice where the Communist Party “disappears” its former officials for weeks or months on end. Beating, hooding, water torture, feces-eating, stress positioning and sleep deprivation are just a few of the techniques used to extract confessions, according to experts on Chinese justice as well as one former official. “My time in shuanggui was tragic and brutal. It was a living hell,” Zhou Wangyan, land bureau director for the city of Liling, told Associated Press.

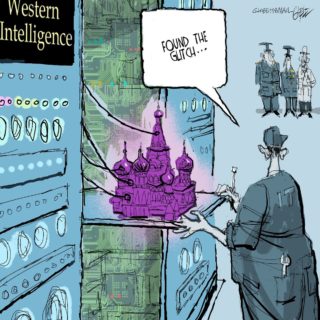

6) The United States remains the big holdout

Even though the U.S. expelled one of the top 100 suspects in 2015, it still has shown resistance to the idea of a formal pact, citing the unreliability of China’s judicial system and mistreatment of prisoners. In the same year, the Obama administration accused the Chinese government of using agents to pressure expatriates wanted on charges of corruption to return home immediately.

7) It’s hard to know if China’s release of former Canadian prison Kevin Garratt was a quid pro quo but it looks that way

According to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s website, the discussions were established by Canadian and Chinese leaders during his visit to China in late August and early September. Among the issues they discussed were counterterrorism and cybersecurity, exchanges on rule of law (i.e. extradition) and consular affairs, the last of which could have included Mr. Garratt’s case. On Sept. 12, Daniel Jean, the Prime Minister’s national security adviser, met a high-ranking Party member to discuss it. The treaty would allow both Canada and China to share the financial assets that suspected Chinese fugitives have brought to Canada.

CRAIG OFFMAN

The Globe and Mail

Published Tuesday, Sep. 20, 2016 4:27PM EDT

Last updated Tuesday, Sep. 20, 2016 9:49PM EDT