The mantra of the 2008-09 financial crisis was “too big to fail.”

Governments in the United States, Canada and other Group of 7 countries spent trillions to backstop and bail out banks, automakers and other large companies for fear that chaos in the financial system would spread to entire economies and trigger a long-lasting depression.

Twelve years later, Canada and the world are in the grip of another economic crisis. But the fears of 2008 have been inverted, amplified and condensed into a much shorter time frame – weeks and days, not months.

The danger point this time is the vast array of small businesses that provide the backbone of employment in Canada and other advanced economies, but are now shuttered in the global fight against the novel coronavirus. Many are neighbourhood stores and restaurants. Others are small and surging startups that are the wellspring of innovation and future prosperity.

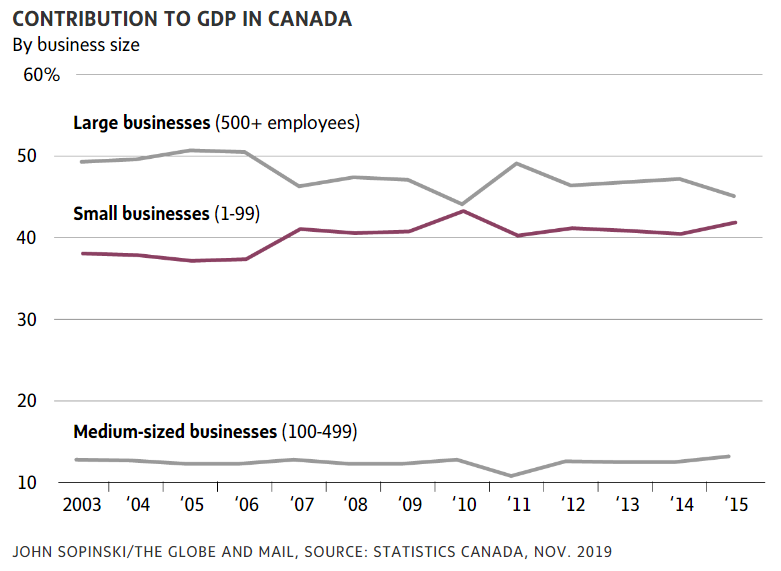

Altogether, the more than one million small businesses in Canada provide seven in 10 jobs and account for two-fifths of GDP.

The threat that policy makers are trying to head off is that those small enterprises will collapse in a wave of bankruptcies, creating a spiral of job losses, dragging down landlords and creditors, wounding banks and impairing the entire economy’s growth prospects for years.

“We have to make sure that all of that together doesn’t go on long enough and get amplified so much as to create another systemic financial crisis,” says Laura Dottori-Attanasio, head of personal and business banking at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. “I think that’s unlikely, but that’s why it’s important that government, banks and everyone lean in to see how much they can do to see we get past this.”

As was the case in 2008-09, however, governments have struggled during the early going.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledged that reality on March 27, when he announced that Ottawa was introducing dramatically expanded wage subsidies of 75 per cent, after days of protest from businesses that the 10-per-cent subsidies unveiled on March 18 were far too small to do much good.

“Canadians are counting on you, and I am counting on you, to come back strong from this, no matter what comes next,” Mr. Trudeau said.

The wage subsidies are part of a barrage of support for businesses of all sizes. Some relief measures come from the playbook in the 2008-09 crisis, including lower interest rates and increased lending capacity from private banks and Crown corporations.

Other early efforts have attempted to target small businesses, including interest-free loans with forgivable portions, and deferment of taxes and other levies – all policies that Ottawa has rolled out in just three weeks.

“You’re going to get the support you need to help rebuild a more resilient and prosperous economy,” Mr. Trudeau vowed.

But in the rapid-fire economic crisis created by the coronavirus, millions of jobs are already at stake, and the debacle threatens to destroy promising startups before they mature into giants. Ottawa doesn’t have time to get picky. It needs to get cash in the coffers of small companies right away before they are overwhelmed.

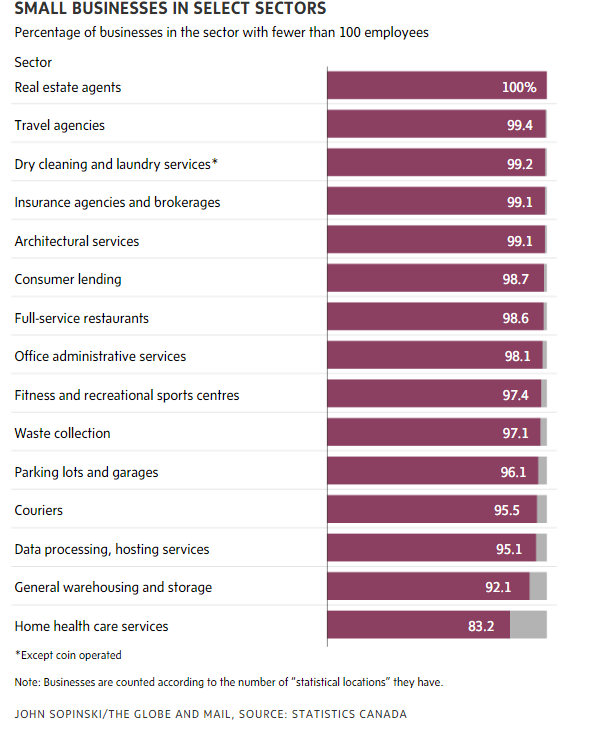

There is no typical small business in Canada or any other country. There are vast ranges of them, which makes it impossible for governments to target individual small companies or even entire sectors of them.

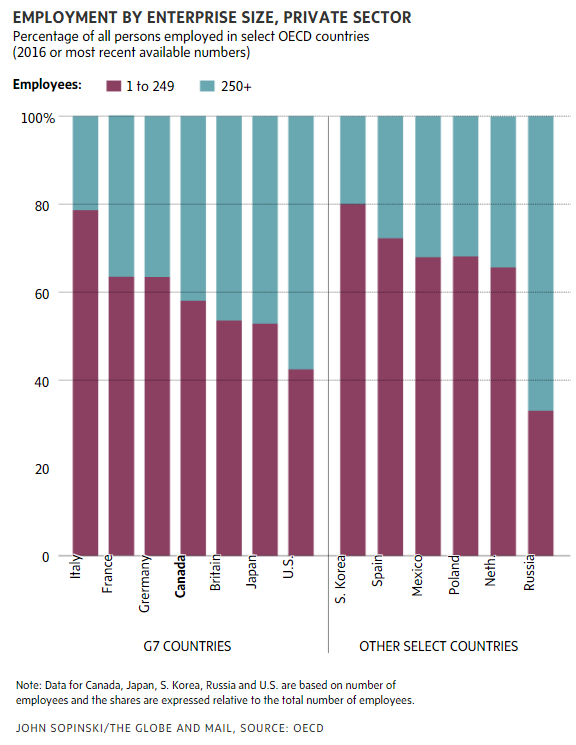

In aggregate, they are hugely important in every advanced economy. In Canada, small businesses (defined as enterprises with 99 or fewer employees) accounted for about 42 per cent of private-sector GDP in 2015, a share that put this country in the middle of the pack for advanced economies.

A report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development said the average proportion of value added to the economy by small businesses with 40 or fewer employees was 38.8 per cent.

On a broader definition of small business, 249 employees or fewer, that proportion rose to 58.6 per cent. (Those figures did not include the U.S. or Canada.)

Potential, of course, is much harder to measure. In 2010, when Shopify Inc. finished first in a ranking of fastest-growing companies by the Ottawa Business Journal, it had just two dozen employees. Now it has more than 5,000 employees and contractors worldwide, and annual revenue of US$1.6-billion.

In the race to rescue small businesses during the coronavirus crisis, different countries have offered quite different aid packages.

In the U.S., the mammoth federal aid package signed into law by President Donald Trump on March 27 includes US$349-billion in forgivable loans for small business that amount to a 125-per-cent subsidy of eight weeks of payroll, to a maximum of US$10-million a company.

Australia, which moved far earlier and more aggressively than Washington or Ottawa to assist small businesses, has a significantly larger small business sector. In Australia, companies with fewer than 49 employees accounted for 54.7 per cent of economic value added in 2015, leading the OECD.

There, the federal government introduced direct subsidies for startups and small businesses on March 12. It has since expanded subsidies twice – once on March 22 and again on March 30.

The initial aid included direct grants of up to C$17,000. The maximum amount of assistance has since been significantly expanded to a ceiling of just less than C$85,000. Loan guarantees are also on offer, along with deferred loans, wage subsidies for trainees and apprentices, and deferral of several government levies.

But in Canada, the lack of such quick direct cash infusions has already left many small companies short of the money they need to cover the most basic expenses, including rent and utility bills.

Veterans of the previous financial crisis say the current one is vastly different in many respects, but the biggest lessons still apply: Ottawa needs to move massively – and fast.

Tiff Macklem was on the front lines of the crisis in 2008. As associate deputy finance minister, and Canada’s G7 finance deputy, he was at a crucial meeting in Washington in October, 2008, where policy makers from the world’s leading economies drew up their battle plan.

In retrospect, that crisis unfolded much more slowly. Problems with U.S. subprime mortgages in 2007 created a liquidity crunch on Wall Street in early 2008, and then gathered force.

In March, 2008, Washington had bailed out investment dealer Bear Stearns. But in September, regulators stood aside as Lehmann Brothers imploded. Stock markets around the world crashed.

“What became clear four weeks after Lehmann was that there were some very large global banks that were weeks away from collapsing,” says Mr. Macklem, now dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto.

At a meeting of the G7 on Oct. 10 in the Cash Room of the U.S. Treasury in Washington, finance ministers and central bankers abandoned incrementalism. Instead, they embraced the radical approach of stating that no other large financial institution could be allowed to suffer Lehmann’s fate. In short: the too-big-to-fail policy.

“That was, at the time, an almost unimaginable solution – temporarily suspending capitalism, guaranteeing all of the world’s largest banks,” Mr. Macklem said.

The finance ministers and central bankers also realized they had to move beyond just reacting to events only to find that the financial conflagration had already leaped over their firewalls. “That was the point that policy makers started to get ahead of the crisis,” he said.

Prudence is not a virtue at such times, and overreaction is inevitable – even necessary. “You have to be extremely bold in your response, you have to do much more than you ever imagined. You have to really try to overwhelm the crisis,” Mr. Macklem said. “You’re seeing policy makers today trying to do that, but the speed at which the crisis is moving is making that very difficult.”

There is another important legacy from 2008: The tools invented to shore up the instability of the financial system were at hand when the coronavirus hit. Increased liquidity for banks, intervention by the Bank of Canada to buy up financial instruments and get cash into the economy, and billions of dollars in credit facilities extended by Export Development Canada and the Business Development Bank of Canada – all were introduced this time by March 13.

To some small business leaders, however, Ottawa’s initial response looked as if it was fighting the last war. “The Department of Finance dusted off its recession file and started pulling out those measures first,” said Dan Kelly, president and chief executive officer of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB).

But Ms. Dottori-Attanasio and Mr. Macklem both say that private banks are much more robust now than they were in 2008, and that gives them the capacity to help shuttered small businesses.

Mr. Macklem commends the government on its approach so far, saying it has learned quickly and rolled out new policies that make sense – wage subsidies for business, in particular. “I do think there is a big challenge in execution,” he adds.

The speed of the economic contraction this time around is one new challenge, Mr. Macklem says. Another is scale. In 2008, the financial crisis was concentrated in advanced economies and the fear was that it would spread globally.

In 2020, the fear of a global crisis has quickly become reality. Canada, rather than being buffeted by the effects of a crisis in other countries, has been hit “directly and suddenly,” Mr. Macklem said.

The source of economic instability is also much different now than in 2008. Mr. Macklem says the current economic contraction is more akin to a natural disaster than a typical business-cycle recession.

But because the banking system is in better shape than in 2008, it can be a “shock absorber” rather than a source of instability, he says.

That view is echoed by Gordon Nixon, who was CEO of Royal Bank of Canada from 2001 to 2014. “The financial institutions, banks included, were part of the problem in 2008. Now they are much more part of the solution,” Mr. Nixon said.

He expects many companies, banks included, will become less focused on immediate profit concerns and more directed toward preserving customer relationships – or in some cases, preserving the customers themselves. “They’ll work very close with their customers to allow them to fight another day,” he said.

Even so, Mr. Nixon says policy makers need to preserve companies now, just as their singular aim 12 years ago was to keep banks around the world afloat. Yes, the resulting government budget deficits were unprecedented then, and unthinkable even a month ago in the current crisis.

But the alternative is far worse, Mr. Nixon says. “That would have been the 1929 Great Depression started. If you had mass bankruptcies, and mass unemployment and mass stress across the system, that is the definition of what a depression would look like.”

For now, it’s very hard for policy makers and small businesses themselves to contend with anything other than immediate pressures.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau has said funds for the 75-per-cent wage subsidies will take three to six weeks to land in bank accounts.

But small businesses simply don’t have enough of a cash cushion to wait that long, says Cato Pastoll, CEO of Loop Financial Inc., which acts as an intermediary to pool investor funds and then lend them to small business. “These are businesses that live paycheque to paycheque.”

Mr. Pastoll’s company achieves that in just two days, he says, suggesting that the government could use the private sector as a partner to deliver subsidy payments.

The delay in disbursing funds may end up defeating the purpose of the wage subsidies, says the CFIB’s Mr. Kelly. “The fear of going bankrupt will drive many businesses to say layoffs are the safest option.

Tech veteran Jim Balsillie is even blunter in his assessment of what a six-week delay means. In the 1990s, Mr. Balsillie and Michael Lazaridis built a basement startup into BlackBerry Ltd., a global powerhouse that helped create the smartphone sector.

Now chair of the Canadian Council of Innovators, Mr. Balsillie says that, for a cash-starved startup these days, six weeks means: “You’re gone.”

The government needs to get cash in coffers of small companies much faster, he says. “The kitchen is on fire. If we don’t look after the kitchen, we lose the whole house.”

Mr. Balsillie does give the government credit for listening to him and a host of others who criticized the initial wage subsidies for small business, capped at $25,000 for each organization, as an insufficient response.

But Mr. Balsillie says the criterion for receiving the higher wage subsidies – showing a 30-per-cent decline in year-over-year revenue – is far too narrow, particularly for startups. And he says he is concerned that Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Morneau have between them warned businesses three times of serious consequences if they abuse the program. (No such warnings have been voiced about benefits being paid to individuals.)

With the economy in chaos, businesses may be legitimately unable to produce precise financials. Mr. Balsillie says he worries that companies close to the cut-off point of the program will pull back for fear of incurring punishment. “They heard us, but then they said, if you game it, you’re in big trouble. Nobody knows what the line is between trouble and safe,” he said.

There is expanded credit on offer to small business, including $40,000 loans that are interest-free with $10,000 that can be forgiven down the road. But for a low-margin retail business, a $30,000 debt could be daunting – a company with a 2-per-cent profit margin, for instance, would need to generate $1.5-million in extra sales.

“They don’t have the ability to repay,” says Michael Smith, one of the organizers of Save Small Business, an ad hoc advocacy group for thousands of small businesses suffering from the coronavirus’s economic fallout.

Mr. Balsillie, along with the CFIB’s Mr. Kelly, also questions the attractiveness and usefulness of such loans, especially since no one knows how long the coronavirus crisis will last.

It would be more effective for governments to introduce an immediate and direct payment to businesses, separate from the wage subsidy program – an approach that a few short weeks ago would have triggered accusations of unjustified handouts. “We do need corporate welfare,” Mr. Balsillie says.

Whether it is days, weeks or months from now, eventually quarantine-like restrictions will be lifted. Businesses will be allowed to reopen, if they can. What will be left of small business depends on how quickly government can deploy and sustain its fiscal lifeline to preserve Main Street jobs and shield innovative firms.

Then, the debate will shift from survival to revival, and to what lessons governments should draw from the coronavirus crisis.

Mr. Kelly said that, ideally, small business would become a more top-of-mind concern for government. But he worries that the current crisis will lead to permanent subsidies for individuals and businesses that increase government’s role in the economy – and put further upward pressure on taxes and already-swollen deficits.

For Mr. Balsillie, the massive government intervention to battle the economic chaos is instructive in that it underscores the hollowness of free-market orthodoxy. The invisible hand has been of little use in a global emergency.

His hope is that Ottawa and other governments recognize that the interventionist approach that has proven so crucial in the short-term fight against the novel coronavirus is of equal importance in the long-term fight to increase the pace of innovation and the growth in Canada’s prosperity. In doing so, Mr. Balsillie says, Canada could join other advanced economies in using the power of government to foster the ideas economy.

“Let’s stop kidding ourselves about how the world works,” he said. “Let’s honestly revisit our thinking, and update our strategy.”

PATRICK BRETHOUR

The Globe and Mail, April 3, 2020