Mackenzie Larochelle, 26, and his girlfriend have what he calls an excellent deal: For a three-bedroom townhouse with a finished basement and two other roommates, they each pay $1,125 a month in rent.

On their own, the Toronto couple would be easily spending much more even for a cramped and rundown space, Mr. Larochelle reckons.

He recalled visiting one unit, the main floor of a duplex, where the storage space consisted of milk crates nailed to the ceiling. The landlord wanted $3,000 a month for it.

But the fact that Mr. Larochelle and his partner each drop more than $1,000 a month in rent to live with housemates has some of his relatives outside of Toronto gobsmacked, he said.

“It’s mind-boggling to my family in Ottawa and elsewhere,” he said.

In fact, four-figure rents for living with roommates – the time-tested way of saving on housing costs – are increasingly common not just in Toronto but across the country. In a growing number of cities, Canadians face advertised rates of around $1,000 a month for a bedroom in a shared home.

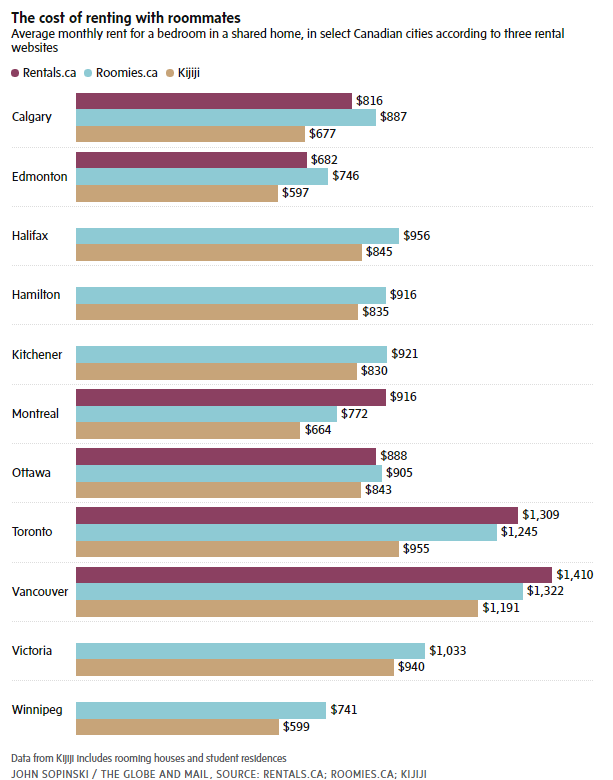

The average advertised rent for a spare bedroom in a home, condo or apartment in Vancouver was $1,410 in March, based on rental listings from Rentals.ca. In Toronto, it was $1,309, and in Montreal $916.

In other urban centres such as Victoria, Calgary, Ottawa and Halifax, as well as several mid-sized cities in Southern Ontario, renting with roommates sets Canadians back $800 to $1,000 a month, on average, according to data from Rentals.ca, online roommate search site Roomies.ca and classified ads site Kijiji.

The high cost of shared accommodations mirrors developments in the broader rental market, in which a mismatch between supply and demand has sent rents soaring since COVID-19 restrictions started to fall away, said Thomas Clement, founder and CEO of Roommates International, which runs the Roomies.ca platform.

The site, which allows users to create ads for available rooms as well as roommate profiles for people looking for accommodation, is currently receiving five roommate profiles for every room listing, he said.

Rental demand surged in 2022, driven by higher immigration, the return of students to university and college campuses and a steep rise in mortgage rates, which forced many prospective home buyers to keep renting. That left the vacancy rate for purpose-built apartments at 1.9 per cent last year, the lowest since 2001, according to a recent report by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.

The rental shortage, which extends to condos and houses, has led to outsized rent increases across most of the country. The national average of asking rents for studio apartments and units with up to three bedrooms was $1,984 in March on Rentals.ca, nearly 10 per cent higher than in March, 2022.

Soaring rents and record-low housing affordability – a result of expensive real estate and high borrowing costs – have led a growing share of Canadians to team up with roommates. That setup has been the fastest-growing living arrangement among adults aged 20 to 34 in recent years, with the number of such households increasing by 20 per cent between 2016 and 2021, according to census data.

The trend likely continued, and possibly accelerated, in 2022. At Rentsync.com, which owns Rentals.ca, data services product manager David Aizikov started noticing a “clear shift” in the demand for rentals on the platform around the start of last year.

Especially in large urban markets, a growing share of house hunters in their late 20s and early 30s was looking for bigger rentals with two or three bedrooms instead of studio or one-bedroom units, he said.

Driving the interest in larger apartments and condos is likely the ability to split the rent with roommates, which usually results in lower monthly costs per person compared with living alone in a small apartment or condo, Mr. Aizikov said.

Renting spare bedrooms is also increasingly common among homeowners looking for ways to afford higher mortgage payments and living costs, Mr. Clement said.

But amid a widespread housing shortage, even rooming with others is becoming less affordable. In Hamilton and Kitchener, two Ontario cities with large student populations – a demographic that often relies on sharing accommodation – average room rents in March were up more than 45 per cent compared to the same month in 2019, before the pandemic, according to the Kijiji data.

In Alberta, which began to see a net influx of young people in 2022, the average room rent in Calgary was up by 26 per cent in March compared to the same month in 2019, the Kijiji data set, which includes student dormitories and rooming houses, shows.

In Atlantic Canada, which has been a destination for Canadians moving from other provinces and for international migrants since 2021, the average room rent on Kijiji was up nearly 49 per cent in Saint John and 38 per cent in Halifax.

Sky-high room rentals are likely to put pressure on postgraduate students to live in crowded quarters and work longer hours while in school, said Mike Moffatt, an economist and senior director of the Smart Prosperity Institute.

The rent increases will also likely make it harder for universities and colleges to attract middle- and lower-income students from out of town, Mr. Moffatt said, a trend that may become particularly apparent in Atlantic Canada, where lower living costs have traditionally helped boost enrolments.

Now, Mr. Moffatt said, “students who would like to go out east – but they’re like, ‘Okay, I can’t afford to live in Halifax’ – maybe they’ll go to Windsor, or Winnipeg, or Edmonton, which are substantially cheaper.”

ERICA ALINI

The Globe and Mail, April 25, 2023