As high as Toronto and Vancouver rents may seem to local tenants, landlords are often losing money on them.

In recent years, many mom-and-pop real estate investors in the two cities have been quietly paying more in mortgage and other ownership costs than they receive in rent, trusting they’d eventually sell at a profit thanks to rapidly rising home values, experts say.

But as interest rates shoot up and price growth slows, some highly indebted landlords are beginning to feel the squeeze more acutely. That financial pain could eventually push rents even higher, some experts warn.

“It’s all about leverage,” said Ron Butler, a Toronto-based mortgage broker.

His firm, Butler Mortgage, is getting daily calls these days from real estate investors in Ontario who’ve used a home equity line of credit (HELOC) for all or some of the down payment on a second property. HELOCs have variable interest rates that lenders typically adjust up or down following movements in the Bank of Canada’s benchmark interest rate.

Canada’s central bank has lifted its key rate by 0.75 of a percentage point so far this year and analysts expect several more hikes over the next few months. The rate increases are rapidly pushing up HELOC payments, a headache for some investors who bought expensive properties at the height of the pandemic housing boom.

“If you bought a rental property seven years ago, which was enormously cheaper – you might even have had positive cash flow – you’ve had time to pay down the HELOC,” Mr. Butler said.

But if you’re an investor who bought in the past 18 months at a much higher price using a HELOC for the down payment and with rent not fully covering your monthly costs, “you now have an issue,” Mr. Butler said.

It’s not uncommon for homeowners who’ve seen the value of their first home soar in recent years to borrow against their home equity with a HELOC to fund the down payment on an investment property, Mr. Butler said, speaking about the Ontario market. Borrowers often don’t disclose to their bank they intend to use the HELOC to acquire a second home, he added.

Once they’ve drawn the cash for a down payment from the HELOC, borrowers typically apply for a mortgage to finance the rest of the real estate purchase, Mr. Butler said.

With HELOC rates climbing, many of those highly leveraged investors are now scrambling to convert their line of credit balance into mortgage debt that comes with fixed payments, according to Mr. Butler. The risk is that some may not be able to do so.

That may be because the additional debt they’ve taken on from the investment property means they don’t meet lenders’ requirements. Another obstacle is the fact that climbing interest rates have raised the bar borrowers must clear to pass the federal mortgage stress test, Mr. Butler said. Yet another hitch is that mortgages, unlike HELOCs, require payments of both principal and interest, resulting in bigger monthly outlays for borrowers, he added.

While Mr. Butler said he hasn’t seen this scenario play out in real life yet in the current environment, he did witness highly leveraged investors run into this kind of trouble in 2008 and 2009, when home prices in Canada briefly dipped after the financial crisis.

Most landlords aren’t as vulnerable as those who’ve used HELOCs to finance their down payments, said John Pasalis, president of Realosophy Realty. Many have fixed-rate mortgages that won’t come up for renewal for a few years. And, up to certain thresholds, even many who have variable rates enjoy fixed instalments, with lenders simply applying more of the monthly payments toward interest rather than the principal as rates go up.

But rising interest rates are nonetheless a concern for landlords who already aren’t able to fully cover their carrying costs of ownership with rent, he added.

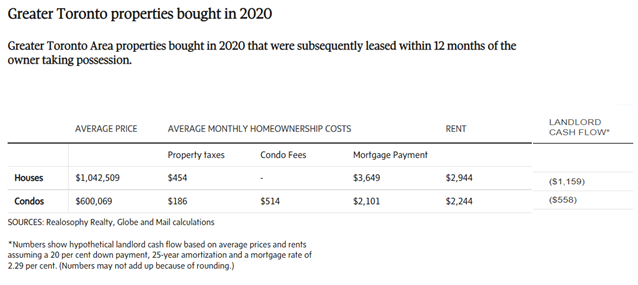

Data provided by Mr. Pasalis suggest many investors who bought properties in the Greater Toronto Area in 2020 with the intention of renting them out aren’t breaking even.

The average price of condos sold that year that were subsequently leased within 12 months of the owner taking possession was just over $600,000, with an average annual property tax bill of $2,235 and average condo fees of $514 a month, Mr. Pasalis’ numbers show. With a down payment of 20 per cent and what was then a competitive five-year fixed mortgage rate of 2.29 per cent, the average monthly carrying cost of an average-priced property would work out to around $2,800, according to calculations by The Globe and Mail. But the average rent for the group properties tracked by Mr. Pasalis was less than $2,250, yielding a monthly loss of over $550.

It’s an even grimmer picture for investors who rented out homes, who could face an average monthly cash flow shortage of nearly $1,160, according to Mr. Pasalis’ data and Globe and Mail calculations.

In a March 2021 report, CIBC deputy chief economist Benjamin Tal and Shaun Hildebrand, president of Toronto-based condo research firm Urbanation, found that 37 per cent of GTA condo rental units registered in 2020 had negative cash flow, with the carrying costs of home ownership outstripping rent by an average of $492 a month for that group.

In Vancouver, anecdotal evidence suggests the share of recent landlords who are losing money may be smaller, said Romana King, director of content at real estate marketplace Zolo and author of House Poor No More.

There are “deeper pockets” in the city’s real estate market, with foreign investors often choosing to buy investment property with cash or required by lenders to make large down payments because they have little financial history in Canada, Ms. King said. Still, negative cash flow for local mom-and-pop investors isn’t rare, she added.

For many real estate investors, the main rationale for sinking hundreds of thousands of dollars into properties they won’t be able to rent out at a profit is the expectation of being able to sell at a much higher price.

In the GTA, “people are investing based on the capital gains,” Mr. Pasalis said. “They don’t mind if they’re cash flow negative each month because they assume the property’s going to be worth $50,000 or $70,000 more by the end of the year.”

For now, cash flow negative landlords can take comfort in the fact that price growth for condos hasn’t softened as much as that of low-rise residential buildings, Mr. Pasalis noted speaking about the Toronto market.

Another group of investors ready to accept negative cash flow are those who buy properties as a future home for their kids, Mr. Tal said. Fear that the offspring will be permanently shut out of the real estate market is common in Vancouver, Ms. King said.

Still, rising interest rates could lead some cash flow negative landlords to offload their properties and dissuade some prospective condo investors from buying, with repercussions on the broader rental market, Mr. Tal said.

While the resulting uptick in supply and slowdown in demand could put some downward pressure on prices, it could have the opposite effect on rents, according to Mr. Tal.

That’s because a marginally smaller investor presence in the condo market will reduce the supply of units available for rent even as demand from tenants remains very strong, Mr. Tal said.

Canada is set to welcome more than 430,000 new permanent residents in 2022 with even higher targets for 2023 and 2024. International students have also been flocking back to the country, adding to the number of newcomers looking for rental accommodation.

The cooling off of investor demand for condos “is not something that is going to derail the market by any stretch of imagination,” Mr. Tal said. But it will increase the upward pressure on rents, he warned.

Larger mortgage payments could also increase landlords’ motivation to raise rents, he said. While rent-control regulation limits many landlords’ ability to ask for more from existing tenants, there are ways to work around the rules, he noted. For example, landlords often raise rents after a renovation that requires tenants to move out.

The end result could be rising tensions between real estate investors feeling the financial squeeze and residents.

“There will be this tug of war between tenants and landlords,” Mr. Tal said.

ERICA ALINI

The Globe and Mail, May 2, 2022