Toronto led the country in homicides last year, but murder rates there were below the national average, and Canada’s largest metropolitan area was also one of its safer cities, according to the latest data from Statistics Canada.

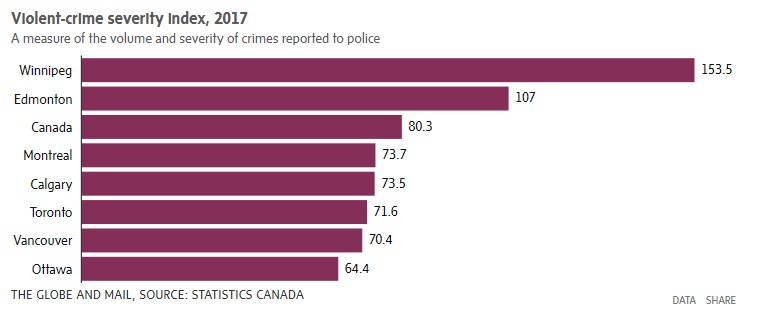

In 2017, Toronto’s census metropolitan area (CMA) recorded 92 homicides, trailed by the CMAs of Vancouver at 52, Edmonton at 49 and Montreal at 46, according to data published on Monday. But Toronto was below the national average on Statistics Canada’s violent crime index, which measures the volume and severity of crimes such as murder, robbery and sexual assault. Toronto ranked 17th of the 33 cities on the index, which was led by Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Ont., Saskatoon and Edmonton.

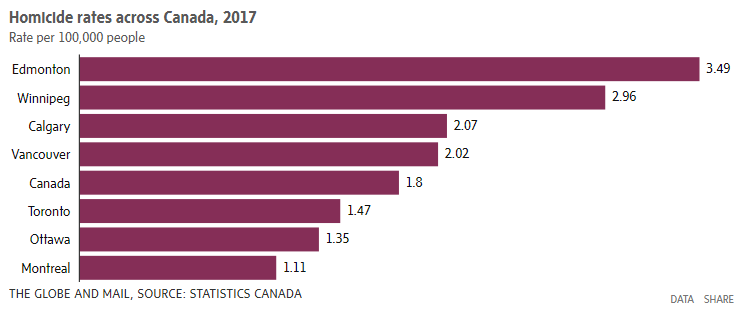

The average rate of homicides was 1.8 per 100,000 people across the country last year, with the most relatively deadly cities being Thunder Bay (5.8) and the Vancouver suburbs of Abbotsford and Mission (4.72), according to Statistics Canada data. Toronto trailed Halifax and Saskatoon in 2017 with a rate of 1.47.

The CMA encompasses the City of Toronto and 23 neighbouring communities.

Using Statistics Canada’s wider Crime Severity Index, which attempts to measure annual changes in the overall seriousness in crime, weighing offence types by their incarceration rates and the average length of prison sentences, Toronto had the third-lowest level of severe crime.

“Typically, Toronto, along with Quebec City, has been in the bottom five,” said Rebecca Kong, chief of Statistics Canada’s policing services program.

Still, while Toronto’s score on this index has been low, “it has been increasing for the last three years,” she said.

Those statistics run counter to a recent spike in gun violence, with 228 shootings this year compared with 84 at this time last year. Last weekend, a man opened fire in a Danforth Avenue neighbourhood, killing an 18-year-old woman and a 10-year-old girl and injuring 13 others.

This year, the City of Toronto has had 58 homicides, according to its police force, 29 of which were shootings. The city’s homicide numbers have been affected by a van attack in April, a single incident that led to 10 counts of first-degree murder.

Toronto could outpace the total number of homicides in 2005, the so-called “year of the gun,” when 53 people were shot dead and 359 were injured. That year, 15-year-old Jane Creba was killed in the crossfire of a gang shootout near downtown mall Eaton Centre on Boxing Day.

In the months and years after that tragedy, the root causes of violence were highlighted and solutions were offered.

United Way Greater Toronto president and CEO Daniele Zanotti said systemic problems such as poverty, income inequality and a sense of social alienation are driving hopelessness among some young people. “Behind some of the youth violence is this deepening and stubborn poverty and inequality that’s … increasingly cementing itself in Toronto,” he said.

It will take a “sustained” and co-ordinated effort among local communities, agencies, police, governments and families to tackle, he said. And he believes economic opportunities – such as apprenticeships and job training – should be enhanced for young people who face barriers.

The data released on Monday showed Ontario reported 10 fewer homicides last year than the year before, bucking a 7-percent national spike – 48 more deaths – in 2017 that was fueled in part by rising violence in British Columbia and a shooting at a mosque in Quebec.

Police reported 660 homicides across Canada last year, which is still a very low base rate compared to 25 years ago, said Neil Boyd, a professor at Simon Fraser University’s criminology school.

“The way in which homicide has changed over time is we have less domestic, we’ve got more gang-related homicides and we’ve seen an increase over the last generation in the use of handguns – but overall, our rates are much lower than they were a generation ago,” he said.

“Of course, it’s always a concern when you get an uptick.”

The federal agency plans to release a more detailed analysis of the latest data in November, but an earlier report into the same homicide statistics from 2016 showed that gang-related deaths were on the rise for that year for the second year in a row after decreasing between 2011 and 2014. That spike in slayings was driven primarily by violence in Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver, with those three census metropolitan areas representing almost half of the country’s 141 gang-related homicides in 2016.

The Special Investigations Unit says they are currently running a parallel investigation with Toronto Police into Sunday night’s shooting on Danforth Avenue, Toronto, with the SIU focused on the ‘interaction’ between police and the suspect that involved an exchange of gunfire.

MIKE HAGER AND TAVIA GRANT

The Globe and Mail, July 23, 2018