Give parents an A-plus for talking up the importance of a post-secondary education for their kids, and a C-minus for backing it up with financial help.

There are student loans, bursaries, scholarships, tax deductions and part-time work to help students pay their tuition and living costs while attending college or university, but they’re not enough. Parents need to chip in as well to keep kids out of deep debt that can take 10 years to pay off.

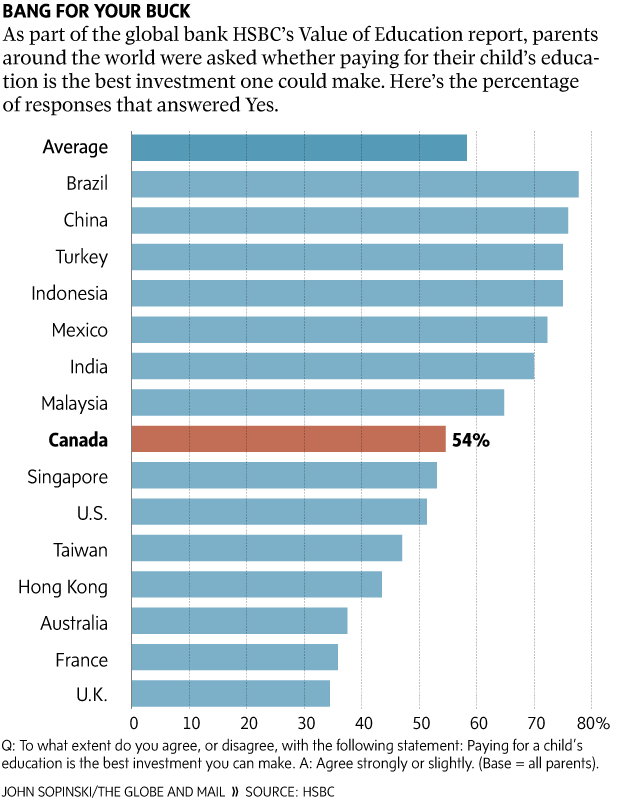

Parents are big supporters of post-secondary education for their kids and believe money spent on college or university is a good investment, according to the Canadian numbers contained in a global survey called The Value of Education: Springboard for Success.

The survey, sponsored by HSBC, asked parents to set priorities in allocating money to help their child financially in life. Fifty-four per cent of the money would ideally go to education, the parents said. The next most important priorities were building funds for long-term investment, at 8 per cent, and a house down payment, 7 per cent.

The survey shows that 82 per cent of parents aspire to have their children attend university, and it suggests that over half of parents believe that paying for a child’s education is the best investment they could make. At least, that’s what parents say for public consumption. “There’s the aspiration, and then there’s the reality,” said Marc Cevey, CEO of HSBC Global Asset Management (Canada).

The federal government’s most recent numbers show there was $35.6-billion invested in registered education savings plans (RESPs) in 2012, and that annual contributions tend to be in the $3.6-billion range. So let’s estimate there’s $40-billion sitting in RESPs, a must-have savings tool that lets parents, grandparents and others put money away for a child’s post-secondary education and receive matching federal grant money.

Statistics Canada’s 2013 population data show there are close to eight million Canadian youngsters aged 19 and under. So figure on there being $5,000 in RESP funds for each child – which is roughly 90 per cent of the national average university tuition cost for one year (not including books or accommodations). True, the parents of young children have a decade or more to keep saving, and some young adults won’t attend college or university.

But the experience of actual members of Generation Y suggests parental help is a surprisingly modest factor in paying post-secondary educational costs. This becomes clear in the yconic/Abacus Data Survey of Canadian Millennials, which was conducted for The Globe and Mail earlier this year and involved 1,538 young people aged 15 to 33. I’ll have much more to say about this data in upcoming columns. For now, let’s look at the role that RESP savings played in helping students afford post-secondary costs.

Asked if their parents used money saved in an RESP to help pay for college or university, just 33 per cent of the young people polled said yes. Another 46 per cent said no, and the rest either preferred not to say or didn’t know. Asked what proportion of their post-secondary costs were paid by RESPs, 60 per cent said zero and another 8 per cent said RESPs covered no more than one-quarter of the total bill.

In parents’ defence, HSBC’s Mr. Cevey said the time to save for a child’s education coincides with the prime years for mortgage payments, daycare and other family-related costs. “From a timeline perspective, there are a lot of conflicting priorities,” he said.

Mr. Cevey also said the financial industry needs to do a better job of helping parents integrate educational savings into their financial planning. The absolute best bit of advice for parents: Start an RESP for your child just after birth. In the HSBC survey, one in three participants said they wished they had started saving earlier for their child’s education.

Can’t young people save enough money themselves to pay for university or college? In most cases, no. A student fortunate enough to work 40 hours per week for the 17 weeks from the beginning of May to the end of August while earning a typical minimum wage of $10.25 per hour would end up with $6,970. Assuming every cent went into savings, that amount would almost certainly fall short of what’s needed for university tuition and books alone.

Your assignment, parents: Improve that C-minus grade for educational savings. Don’t just talk about the importance of a post-secondary education.

ROB CARRICK

The Globe and Mail

Published Monday, Apr. 28 2014, 4:36 PM EDT

Last updated Monday, Apr. 28 2014, 8:13 PM EDT