While inflation has massively increased the cost of a postsecondary education by driving up prices for tuition, food and rent, at least one thing has not kept pace with soaring education expenses: registered education savings plans.

The contribution room available for parents to save for their children’s schooling has not increased, nor have the government grants that are part of the popular program.

And the federal government is in no rush to expand RESPs any time soon.

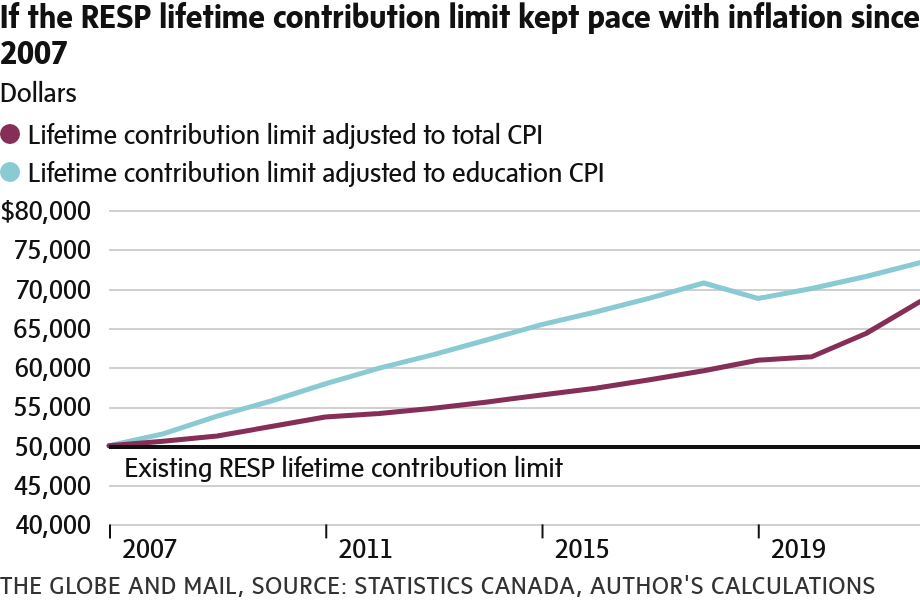

The lifetime RESP contribution limit per child of $50,000, and the maximum $500 annual grant, up to a lifetime limit of $7,200, that Ottawa kicks in through the basic Canada Education Savings Grant, or CESG, have not changed since 2007. Since that time, the average cost of tuition, food prices and rent in Canada’s largest cities has risen by between 50 and 60 per cent.

If RESP caps had merely grown at the same rate as Canada’s consumer price index since 2007, the lifetime contribution limit would be more than $68,000 today, while the lifetime grant would be $9,800.

Sébastien Mc Mahon, chief strategist and senior economist at iA Investment Management, points out that even this calculation understates the erosion in savings potential, since the education component of Canada’s CPI basket of goods and services has risen faster than overall inflation during that time.

“When you look at education services, you’re especially losing purchasing power,” he said.

Put another way, if RESPs and government grants had matched education services inflation since 2007, the lifetime contribution limit would be more than $73,000, while the lifetime grant limit would exceed $10,500.

“There’s no question the RESP contribution limit and the lifetime grant limit have not kept up anywhere close to inflation or the increasing cost of education,” said Dan Bortolotti, a portfolio manager with PWL Capital. “It needs to be updated, but I’m not optimistic that will happen.”

While RESPs date back to the 1970s, the current incarnation evolved in 1998. Under the program, parents can put money into a tax-sheltered investment account, which the government matches with a grant of 20 per cent each year, up to the maximum annual grant of $500. Additional grant amounts are available for low-income families.

RESP 101: How to use a RESP to save for your child’s education

Yet the last time substantive changes were made to RESPs was 16 years ago, when Stephen Harper’s Conservative government did away with annual contribution limits, and the lifetime contribution limit was raised to $50,000 from $42,000. The annual basic grant amount was also raised to the current level, from $400.

There are several reasons to doubt another hike to match inflation is in the offing.

For one thing, the current Liberal federal government believes the existing amounts are ample, and says parents have other options for saving, if needed.

“Families that have contributed the maximum amount to an RESP, or enough to no longer attract matching grants, can also save for their children’s education through the tax-free savings account,” the federal Finance Department said in an e-mailed statement, which noted that the cumulative TFSA limit for individuals now stands at $88,000.

Unlike with RESPs, TFSA contribution limits are indexed to inflation and rise in $500 increments, as happened this year when inflation pushed the limit’s annual increase to $6,500, after it had sat at $6,000 since 2019.

Another reason the federal government may not feel an urgent need to index RESP lifetime limits or grants is that few families are taking full advantage of RESPs as it is. In 2019, just over half of families with at least one child under 18 had opened RESP accounts, according to Statistics Canada, while the median RESP investment was $10,485. For families in the bottom 20 per cent of income earners, the median RESP investment was around $3,300, rising to $22,050 among the highest earning families.

“There’s a strong argument for indexing the limit to inflation, but you can also question whether it will make a dent, because a large portion of families are not using RESPs at all,” Mr. Mc Mahon said.

There’s also the fact that, as the above figures show, the wealthier the family, the more likely they are to take advantage of RESPs for their children. This means RESPs, at least as currently structured, are out of step with the Trudeau Liberals’ oft-repeated pledge to fight inequality.

“As much as I like the program, you have to admit a lot of people use it just to get the grant and nothing else,” Mr. Bortolotti said. “They would have been able to pay for education without the program, so is that really helping more kids go to university?”

But even some of the RESP’s most prominent critics believe lifetime limits and grants should keep up with inflation. The fact that the main beneficiaries of RESPs and CESG payments are middle-class and upper-middle-class families should be a separate matter from the question of indexing, said Kevin Milligan, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia whose research has shown that RESPs do little to promote access to postsecondary education.

“As an accessibility measure, RESPs are poorly designed. But as an affordability measure for middle-class families whose children are likely going to school anyway, there’s a solid argument to reindex,” Prof. Milligan said. “Having some fiscal parameters of the tax system indexed and some not erodes the choices that were made when different programs were created in a very arbitrary way.”

The issue is ripe for political debate, particularly with the Conservatives hammering the Liberals on inflation. In the 2019 federal election, then-Conservative leader Andrew Scheer promised to expand the grant portion of the RESP program to an annual maximum of $750. He also said the Conservatives would boost the allowable lifetime grant limit to $12,000 from $7,200, an amount that hasn’t changed since the creation of the CESG in 1998.

If the lifetime grant limit itself had kept pace with inflation since 1998, it would be slightly more than $12,000 today.

Mr. Scheer’s successor, Erin O’Toole, dropped the pledge in his unsuccessful bid to unseat the Liberal government in 2021.

But with the surge in education and living costs since then, an enhanced RESP could be a potent campaign promise for whenever the next election takes place.

“An increase of the RESP could have appeal in that critical suburban vote that is getting squeezed by the rising cost of living,” said pollster Nik Nanos of Nanos Research. “For the Conservatives it could be a gateway policy to engage middle-class Canadians.”

JASON KIRBY

The Globe and Mail, February 21, 2023