An unusual partnership aims to save a glorious remnant of the prairies.

A man and a woman stand at the edge of a buffalo jump. Generations ago, Blackfoot hunters herded thundering bison over the precipice to their deaths. Today, this clifftop is the perfect place to take in the majesty of the McIntyre Ranch, a sea of rolling grassland in southern Alberta.

The man, tall and rangy with a thick white beard, raises a sun-browned arm to point to its distant borders. The woman, petite with windswept blonde hair, crouches to examine the turf, her blue eyes narrowing to a squint as she identifies the multitude of plants and grasses that thrive in the dry earth.

Ralph Thrall III and Leta Pezderic are unlikely collaborators. Mr. Thrall, 59, is a third-generation rancher who jokes that he is “a redneck for a reason.” He is responsible for thousands of cattle and 22,000 hectares of land, an area more than a quarter the size of Calgary. Ms. Pezderic, 42, is a university-trained environmentalist who cuddles barn kittens and leans out of truck windows to capture meadowlarks and ground squirrels with her long-lens camera.

Ralph Thrall III, president and CEO of McIntyre Ranching Co. Ltd., talks with Leta Pezderic, grassland stewardship manager for Nature Conservancy of Canada in Alberta, as they drive through the McIntyre Ranch near Magrath, Alta. on Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2023. IAN MARTENS/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

His conversation twists and doubles back like a prairie river. She likes to get right to the point, and isn’t afraid to give him a tap on the shoulder when he doesn’t.

But, here, rancher and environmentalist are united in a common cause. Both love this landscape with a nerdy passion. (Don’t get them going about rough fescue.) Both are determined to preserve its austere beauty for future generations and awaken us all to the splendour of the grass.

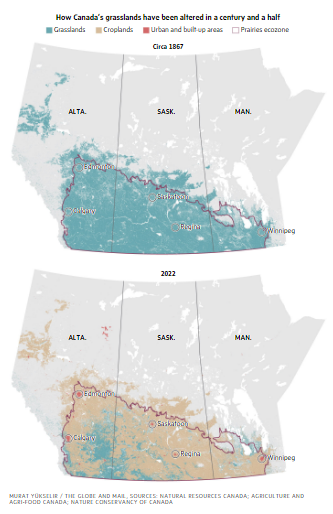

Canada’s grasslands are disappearing at an alarming rate. About four-fifths of the vast ecosystem that once stretched unbroken from present-day Edmonton to Winnipeg is now gone, plowed and seeded to help feed Canada and the world.

Much of the remnant is under threat. About 60,000 hectares a year is turned over to croplands, pasturage and other uses, a rate of proportional loss four times that of the Amazonian rain forest.

That means trouble for the many creatures that depend on these lands, from the yellow-bellied marmot to the sharp-tailed grouse.

The ranch hosts 350 kinds of plants, 130 of birds and 25 of animals. About 1,200 hectares of wetlands, too, including everything from small basins to sprawling marshes.

It means trouble for the planet, too. Grasslands store billions of tonnes of carbon in their deep roots, the majority of it released into the atmosphere when they go under the plow.

The ranch hosts 350 kinds of plants, 130 of birds and 25 of animals, as well as about 1,200 hectares of wetlands. COURTESY OF LETA PEZDERIC

The grasslands need grazing animals to stay healthy. Without it, some of the grasses would run wild and crowd out other species, letting invasive plants move in. COURTESY OF LETA PEZDERIC

At the McIntyre Ranch, Mr. Thrall and Ms. Pezderic are taking a stand. It may seem an odd place to do it. A ranch is a place where cattle are branded, castrated and sent off for slaughter so people can enjoy their steaks and burgers. While they live, those munching, belching beasts produce a lot of methane, a greenhouse gas worse than the carbon dioxide from your car’s tailpipe.

But the grasslands need grazing animals to stay healthy. Mr. Thrall’s herds stand in for the millions of bison that used to roam here. Without cattle-grazing, some of the grasses would run wild and crowd out other species, letting invasive plants move in. So the goal of proud turf-huggers like Ms. Pezderic is not to shut down ranches and turn them back to wilderness, as you might do with a stand of forest in British Columbia or a wetland in New Brunswick. It is to keep the ranchers ranching and the cattle chewing.

To that end, Ducks Unlimited Canada and the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Ms. Pezderic’s employer, have made what they call a historic deal with Mr. Thrall and his family. Accepting what is called a conservation easement on the property, the Thralls have agreed to keep the ranch more or less as is in perpetuity. That means they cannot convert any of it to more-profitable cropland, as some hard-pressed ranchers have done. They have also agreed to limit the number and type of roads, dams and buildings.

When the deal was announced in June, the Conservancy called it the biggest private conservation project on Canada’s prairies, preserving one of the last undisturbed, privately held tracts of native grassland in North America.

Ms. Pezderic and Mr. Thrall are working side by side to put the deal into effect. She is the grassland stewardship manager for the Conservancy in Alberta; he is chief executive of the ranch, which he owns with his three younger siblings: a sister and two brothers.

After years of feuding, says Ms. Pezderic, environmentalists and ranchers are realizing that, “no, actually, we need one another to accomplish each other’s goals.”

On an afternoon-long tour in Ms. Pezderic’s big black pickup, they show off the ranch’s glories: the sandstone hoodoos where a prairie falcon has been nesting; the glittering lake where migrating ducks and pelicans rest; Buffalo Rock, a huge boulder, deposited on a slope by a passing glacier, that was worn smooth by bison rubbing themselves against it.

Wildlife is everywhere: a herd of elk stands silhouetted on a ridge; a coyote trots across the road; a badger throws up clouds of dirt as it burrows itself to safety; an endangered ferruginous hawk, the biggest of its species in North America, sails by.

But what really gets Ms. Pezderic and Mr. Thrall pumped is the grass. They point out some of the many types that thrive on the ranch: porcupine grass; June grass; Idaho fescue, a tiny bluish plant; and above all, rough fescue, a prairie classic that grows in tough, dense bunches. They trip over each other’s words as they list its virtues: the roots, up to one metre deep, that allow it to resist drought; the blades that hold their nutritional value in the fall and winter when other grasses store their nutrients underground. Mr. Thrall is such a fan that he ordered a vanity plate that reads RUFFESQ.

Smart ranchers like him don’t let the cattle overgraze it. Once the animals chew down too far, the plant will die, which is one reason that seeing it in such abundance is becoming so rare.

Ms. Pezderic says she has to pinch herself every time she visits the McIntyre, which she calls “the most remarkable tract of grasslands I’ve ever set foot on, and I’ve seen a lot.” Mr. Thrall, who put aside a dream of a career as professional golfer when his dad called him back to become ranch foreman, says he is glad his family can play a role in preserving such a prairie gem. “My gut and my mind tells me it’s the right thing to do in order to maintain balance on this planet.”

His grandfather, the original Ralph Thrall, bought the ranch in 1948 after the death of his friend W.H. “Billy” McIntyre, whose strapping Texas-born father founded it in 1894 with cattle shipped in from Utah. In a pamphlet Billy wrote about the ranch’s history, he said that there were times when he would have sold it for a nickel, given the hardships of ranching, but that “if you once get the fever of livestock-raising into your blood you never get rid of it.” In ranching, he wrote, “the more you put yourself into it, the more you get out of it.”

The current Ralph Thrall feels the same way. After taking over from his father, who never really caught the ranching bug, he threw himself into restoring and improving the spread: its turf, its 350 kilometres of fencing, its magnificent old barn with huge wooden beams.

The Nature Conservancy first approached the family around 30 years ago. It couldn’t reach an agreement with the Thralls, so it tried again in 2020. This time, Mr. Thrall was ready to listen. Getting to a deal still took close to three years of lawyering, appraisals and negotiation. Because an easement bars cultivation of the land, it can lower the value by up to 40 per cent. The Conservancy had to raise millions from governments and donors to compensate the Thralls and fund the ongoing care of the habitat. It is still trying to raise a final $2.3-million.

And that is only the start. Caring for this bounty will be an ongoing effort. The Conservancy will press ahead with counting all the plants and creatures so it can make plans for their continued survival. It has already inventoried the grassland songbirds and raptors, many of them at risk, including the magnificent golden eagles often seen soaring here. Now it is working on bats. All eight of the species native to this part of Alberta have been spotted.

And Mr. Thrall? Mr. Thrall will keep ranching. It’s a hard slog however you do it, but the Thrall way is double the trouble. Unlike most ranchers, he doesn’t feed his livestock forage, like hay, in the winter. Instead, they stay out on the range, which is often blasted clear of snow by the winds that whip this part of the world.

Ms. Pezderic and Mr. Thrall are working side by side to preserve one of the last undisturbed, privately held tracts of native grassland in North America. IAN MARTENS/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

To sustain the grasses that sustain the cattle, his seven ranch hands must keep shifting the herds from section to section, allowing the turf to regrow in their absence. Only a quarter of the spread is being grazed at any time. Choreographing the movement of 5,600 cattle (up to 9,000 in the summer) is no mean feat. Though much of it can be done by vehicle, he insists his hands know how to ride and rope so they can treat a sick animal in the field.

Three years of drought have compounded the challenge. “We are in a dire situation right now,” he says. “We don’t have enough grass to get us through the winter.” The elk are eating a lot of what’s left and hunting is prohibited on the ranch.

But Mr. Thrall knows he is lucky to be the steward of such a place. His partner in the mission, Ms. Pezderic, feels equally blessed. Her work here means she will be coming down often from the property along the Oldman River where she and her husband are raising three boys.

She just hopes their love of the grass rubs off on others. These lands aren’t as charismatic as the Rockies or the old-growth forests of the West Coast. “Anybody can love the mountains, but it takes soul to love the prairies,” she says, echoing a Western saying. Some people drive right through them with barely a second thought. If they donate to save a species, it’s more likely to be the orangutans of Borneo than the little burrowing owl of Alberta’s prairies.

A visit to the McIntyre Ranch – its grandeur secure now for generations – might just change their minds.

MARCUS GEE

The Globe and Mail, October 6, 2023