Since Russian President Vladimir Putin’s actions this week are a carefully calculated bet, it is likely that the West will have to consider sanctions as a long-term strategy.

With Russian tanks inside their borders and missiles landing in their major cities, Ukraine’s leaders made it abundantly clear: They are desperate for economic body blows against Russia.

Fully aware that NATO’s armed forces wouldn’t come to the rescue, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba went public this week with an appeal for maximum economic pain, something powerful enough to make Russian President Vladimir Putin rethink his illegal attack.

“I will not be diplomatic on this,” Mr. Kuleba wrote on Twitter. “Everyone who now doubts whether Russia should be banned from SWIFT has to understand that the blood of innocent Ukrainian men, women and children will be on their hands too. BAN RUSSIA FROM SWIFT.”

Belgium-based SWIFT, or the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, is a messaging platform that lubricates the global financial system. Designed to replace Telex machines, it is now used by 11,000 financial institutions, and more than six billion messages are transmitted over the network each year.

While it isn’t the pipeline for wiring money, SWIFT provides all the instructions for the transfers, which inextricably links it to actual financial flows – so much so that banning Russia from using SWIFT could make the country’s trade slow to a trickle.

Mr. Kuleba’s plea was quickly supported by politicians in the United States, including House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff and Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Robert Menendez. Yet President Joe Biden and Western allies opted Thursday against going that far – at least for now.

Instead, President Biden reasoned that just cutting many Russian banks out of the U.S.-led financial system and, crucially, from many U.S.-dollar dominated transfers, will cause enough pain for Russia, while preserving some crucial trade with the country that benefits the West.

For besieged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and other leaders in favour of maximum pressure, being so rational was a disappointment. Yet the reality is nuanced, and there’s no escaping that. All possible sanctions available to the West are well-known by Mr. Putin, and he has re-tooled Russia’s financial system to cushion their blow after he annexed the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in 2014.

Because Mr. Putin’s actions this week are a carefully calculated bet, it is likely that the West will have to consider sanctions as a long-term strategy. “If your goal is to stop Putin in his tracks, it’s not going to work,” Alexandra Vacroux, executive director of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University, said in an interview. “He’s decided that the economic cost of invading Ukraine is worth it.”

Complicating matters, economic warfare “is not a missile strike; it’s more like a cluster bomb,” Ms. Vacroux added. “You wipe out all sorts of things and see what’s left afterwards.” And what makes it so tricky is that it can take months – or even years – for an economy to deteriorate. By then, Ukraine could be in a very different place.

Decades ago, financial warfare was barely a consideration for Western governments. Although sanctions were deployed from time to time, they were more like blanket prohibitions, such as the comprehensive U.S. trade embargo against Cuba, imposed in 1962.

It’s only in the past 20 years, since 9/11, that financial warfare has become what the U.S. Treasury Department calls a “tool of first resort” to address a range of threats to national security, foreign policy and the U.S. economy. This thinking has pervaded Western financial markets, because global trade is predominately conducted in U.S. dollars, which allows Washington to call the shots.

There are multiple reasons why sanctions are now so readily deployed. For one, the U.S. political landscape has become much more divided, particularly in Congress, making traditional warfare a much more contentious issue.

Economic measures, meanwhile, can be applied by executive order by the U.S. president. “It’s an irresistible tool,” Britt Mosman, a former Treasury Department attorney-adviser who is now a partner at Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP in Washington, D.C., said in an interview.

Many Western countries have also been burned by so-called never-ending wars in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan over the past two decades, weakening voter support for traditional battles.

In response, the U.S. and its allies have fine-tuned their financial prohibitions, and tied them to strict punishments. In the U.S., any violations of sanctions can be subject to criminal and civil penalties, and corporations and individuals can be held criminally liable.

The same goes in Canada, where contravening sanctions is a criminal offence that is enforced by the Canadian Border Services Agency and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The efficacy of sanctions is a highly debated subject, but they are widely seen as working in Iran after President Obama imposed them in his first term to cut the Iranian economy off from Western finance. Crucially, the blanket prohibition prevented many countries from buying Iranian oil, which crippled its economy and brought Iran’s leaders to the table to negotiate its nuclear program and their push to develop a nuclear weapon.

President Obama also imposed sanctions on Russia after Mr. Putin invaded Crimea, but the effect of those restrictions is much more debatable because they weren’t broad bans akin to those applied to Iran. Instead, they consisted of travel bans for prominent individuals and rules against long-term financing for some prominent Russian companies, among other things.

Global oil and gas prices also started to tank that year, which had a dismal effect on Russia’s energy-dependent economy. Despite the noise, the International Monetary Fund has estimated the sanctions, coupled with Russia’s countersanctions, wiped 1 per cent to 1.5 per cent off of the country’s GDP in 2015.

With its economy teetering, Russia started retooling its financial system after it seized Crimea. To start, the government slashed public spending and ordered financial institutions to fix their balance sheets. Mr. Putin also spent heavily to rebuild Russian manufacturing and food supply. In the same way that the U.S. is now onshoring production capabilities it had outsourced to China, Mr. Putin established Russian-made options for many goods that were imported, and went so far as to ban some food imports from the EU.

Russia also set up a kitty for excess oil and gas revenues, akin to the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund and Norway’s oil sovereign wealth fund. Russia’s National Wealth Fund now has roughly US$175-billion stashed away. The war chest can provide emergency funds if Russia’s economy is dealt a blow.

At the same time, Russia has aggressively pursued so-called “de-dollarization” – distancing itself from the U.S. dollar as best it can. The goal is only partially achievable, considering exports such as oil are sold in U.S. dollars, but Russia’s dollar-denominated foreign currency reserves held by its central bank are now just 16 per cent of the total, down from 40 per cent in 2017, according to Bloomberg. Russia has also worked to shed U.S. dollars from its National Wealth Fund.

In all, what Mr. Putin has built is now referred to as “Fortress Russia.”

Reading President Putin has always been a complicated task, but his attack on Ukraine this week has made Western allies realize that deploying sanctions with a scalpel isn’t going to cut it.

After unveiling a new round of prohibitions on Tuesday, they doubled down two days later with some intense measures designed to cut off Russia’s largest banks from the U.S.-led Western financial system.

While much more aggressive than the opening salvos in 2014, they’re not a full-blown ban on doing business with Russia, as it was with Iran. The affected banks now include Russian’s two largest, Sberbank and VTB. U.S. officials said Russia’s ability to access global markets and utilize the U.S. dollar “will be devastated.”

To spell out the implications, the U.S. Treasury Department noted that Russian financial institutions conduct about US$46-billion worth of foreign exchange transactions globally per day, and 80 per cent of those are in U.S. dollars.

Notably, the U.S. did not enforce the same rules on Gazprombank, which is Russia’s main vehicle for conducting oil and gas transactions.

Western allies also have not imposed a ban on Russia using SWIFT, for reasons that are likely tied to their soft touch on Gazprombank. Late Friday, Prime Minster Justin Trudeau came out in support of banning Russia from the messaging network, but said European countries are still “reflecting” on it.

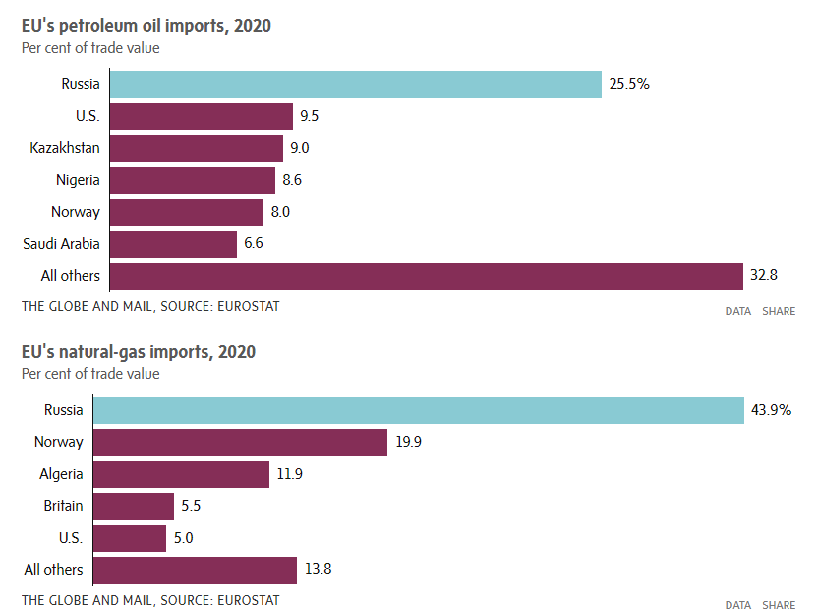

No one is saying it publicly, but the EU relies on Russian energy – especially in the winter. Russia accounted for 44 per cent of all natural gas imported by the EU in 2020, according to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical agency, which is the most of any source country. Russia also accounted for 26 per cent of all oil that was imported – again, the most of any country.

The reason Iran could be punished so severely by President Obama was because Iranian oil was a far-away thought for Western allies. If Russia were banned from SWIFT, it would be extremely difficult for the countries that rely on its energy the most to find ways to pay for it.

To appreciate the complications, consider how Canada’s hands were tied after China detained Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig in 2018 in retaliation for the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou. The West’s reliance on China in globalized supply chains gives the country major economic leverage.

Couple that with the tough reality that economic sanctions won’t make Russia flee from Ukraine immediately, and the cost-benefit analysis becomes much more complicated.

“There’s no scenario in which sanctions accomplish our political goals in the next days or weeks, or probably even months,” said Chris Miller, co-director of the Russia and Eurasia Program at the Fletcher School, which is part of Tufts University in Massachusetts.

Mr. Miller is all for tougher sanctions. “My personal view is they’re not enough; there’s more to be done,” he said of the existing measures.

But he also appreciates what the West is trying to do. “The way to think about it is not, ‘How do we cause maximum pain in Russia tomorrow?’” he said. To this end, he cited a ban on high-tech exports to Russia. Western allies and Asia control the key technologies used to modernize a military, and the best goal now may be to limit Mr. Putin’s capabilities the next time he wants to attack.

“We have to think long-term,” he said.

TIM KILADZE

The Globe and Mail, February 25, 2022