By a rough estimation, 2016 featured at least a dozen films about zombies, the living dead, the walking dead and the generally undead. Few of them are likely very good – although the title Zoombies raises intriguing possibilities – and most never saw the inside of an actual theatre, preferring to litter the crusty bottom of your streaming queue. But the hunger for Z-grade zombie flicks combined with the juggernaut of AMC’s The Walking Dead, the white walker-centric Game of Thrones and the development of everything from Zombieland 2 to World War Z 2 proves that the undead are undeniably big business. You can thank, or curse, George A. Romero for that.

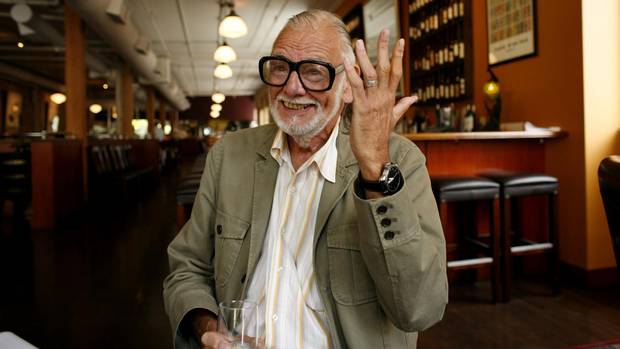

Romero, who died Sunday at 77, seized an opportunity in the film industry that is mostly out of reach for today’s filmmakers: He created, with his bare hands, an entire new genre, free from the influence of Hollywood. And that genre, the zombie film, has both radically changed the entertainment landscape and perhaps poisoned it.

Born in the Bronx in 1940, but making a name for himself in Pittsburgh after graduating from Carnegie Mellon University, Romero engineered a new form of filmmaking from scratch. While working at a local production house, the commercial director scratched together just barely enough money – a bit more than $100,000 (U.S.) – to make his masterpiece, 1968’s Night of the Living Dead. The film would not only introduce audiences to a new breed of cinematic monster – the slow and ravenous zombie, whose parasitic disease meant that not even death offered a final escape – but would change the horror landscape itself, introducing socio-political subtleties to a form of entertainment most wrote off as cheap and superficial.

That first film – filmed in black and white, and tame in its violence compared with Romero’s later efforts and those of his acolytes – caught the eye of critics for its casting of African-American actor Duane Jones as the lead and hero Ben, practically the only man of integrity in a movie crowded with cowards and easy zombie chum. Ben survives the night of terror until its final moments, when he’s shot and killed by an easily spooked white posse who mistake him for one of the undead and dispose of his body like just another bothersome corpse. It’s a devastating moment that neatly and cruelly echoed reality, adding substantial academic weight to a blood-and-guts B-movie.

Although Romero regularly admitted any racial indictments were accidental – Ben was written by Romero and John Russo as a white man, and Jones simply happened to be the best actor available – the narrative was set, and Romero would go on to load his zombie films with nervy political undercurrents, creating a new genre that today might be sloppily pegged as Woke Horror. (I cringe at writing that, but you know it’s true.)

So 1978’s excellent and terrifying Dawn of the Dead serves as a critique of consumerism – all those zonked-out, half-rotting bodies shuffling through a shopping mall; 1985’s legitimately gross Day of the Dead a treatise on the perils of militarism; 2005’s urgent but sloppy Land of the Dead a fevered protest against capitalism; 2007’s mostly awful Diary of the Dead a “get-off-my-lawn” screed on narcissistic millennials; and 2009’s Survival of the Dead a quarter-hearted shake of the fist against all of the above.

In between Romero’s four-decade adventure in zombie land (he took frequent breaks to make a series of underrated films, including the Stephen King adaptation Creepshow and the wonderfully twisted Martin), the rest of Hollywood took note of the director’s success and promptly eviscerated the genre from the inside out. Some projects successfully married Romero’s political instincts and affinity for gore to create some true surprises (Zack Snyder’s 2004 Dawn of the Dead remake works after all these years). Some helped spotlight the mad ambition of cinema’s biggest talents (Peter Jackson’s 1992 splatterfest Braindead, Edgar Wright’s 2004 comedy Shaun of the Dead, Danny Boyle’s sparse but frenzied 2002 effort 28 Days Later). While others simply ensured that the “Z” category on your Netflix account is that much more overpopulated.

While Romero shunned Hollywood for fear of how it might dilute his vision and cheat him out of his rightful profits – even going so far as to physically work out of its reaches, mostly filming in Toronto in his later years – Hollywood could not help but resurrect what Romero created again and again, to arguably diminishing returns. AMC’s The Walking Dead is seven seasons strong now, but it is difficult to convince its audiences as to exactly why. World War Z was a delightfully Romero-inspired property when it was simply a faux-travelogue by Max Brooks, but its cinematic adaptation didn’t exactly convince anyone of a need for a sequel (which we’re getting, so too bad). Ditto the planned Zombieland follow-up, a reboot of the Resident Evilfranchise and whatever Pride and Prejudice and Zombies was supposed to be. What was once Romero’s subversive domain (even if it was accidentally so, at first) has become the paper-thin mainstream.

Last year, Romero admitted he was having trouble raising money for a new zombie outing – not entirely surprising given the diminishing returns (both financially and critically) of his past few films. But for this master of horror to be placed on the industry sidelines while his devoted but less skilled contemporaries closed deal after deal was disheartening.

Romero eventually secured some sort of financing, though, and was planning to shop his new effort, Road of the Dead, at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival’s co-production market this month. Thanks to Romero’s name, it will surely be picked up. And who knows, it might even be good, with its script by Romero and direction by long-time stunt collaborator Matt Birman. In death, to use one of the easiest metaphors ever provided, George A. Romero may find new life. For everyone else, there will be episodes of The Walking Dead.

BARRY HERTZ

The Globe and Mail

Published Sunday, Jul. 16, 2017 8:03PM EDT

Last updated Sunday, Jul. 16, 2017 11:31PM EDT