Cars drive past an electric charging station in Oakville, Ont., the affluent neighbourhood that has the highest adoption rate for zero-emission vehicles in Ontario, around four vehicles per 1,000 people. MELISSA TAIT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Quebeckers and British Columbians are far ahead in switching to green transportation thanks to legislated sales targets and other incentives.

As manager of sustainability and climate change for the District of Squamish, Ian Picketts tries to practise what he preaches.

That includes driving an electric vehicle. Bought new, a departure for the self-described cheapskate, his 2020 Chevrolet Bolt is now a mainstay for him and his partner, who uses it to travel to Vancouver about once a week for her job.

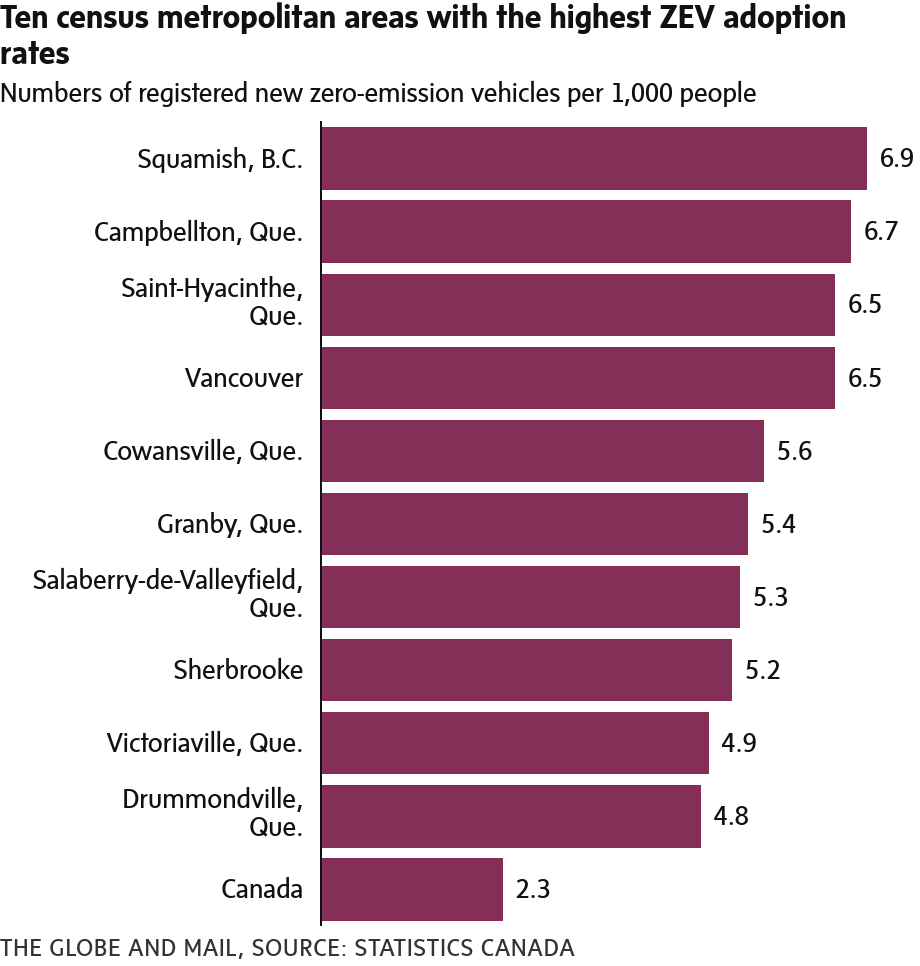

Vehicle owners like Mr. Picketts have helped make Squamish, B.C., a welcoming spot for electric vehicles. According to Statistics Canada registration data for new zero-emission vehicles, the Squamish Census Metropolitan Area had the highest adoption rate in Canada in 2021 for ZEVs, at 6.9 per 1,000 people.

Mr. Picketts was not surprised to hear Squamish was an EV hot spot.

“I think we are in the process of seeing a paradigm shift,” Mr. Picketts said in an interview, citing improved charging infrastructure and advances in vehicle design and manufacturing.

“There are parts of my job where I’m not sure how we’re going to get there. But EVs are one of the things where I am extremely confident that we are going to meet our targets.”

For Canada as a whole, the rate was 2.3 per 1,000 people. Of the top 10 census metropolitan areas (CMAs) ranked by EV adoption, two were in B.C. and eight were in Quebec. That’s not a coincidence. Both provinces have legislated ZEV sales targets: Quebec since 2016 and B.C. since 2019.

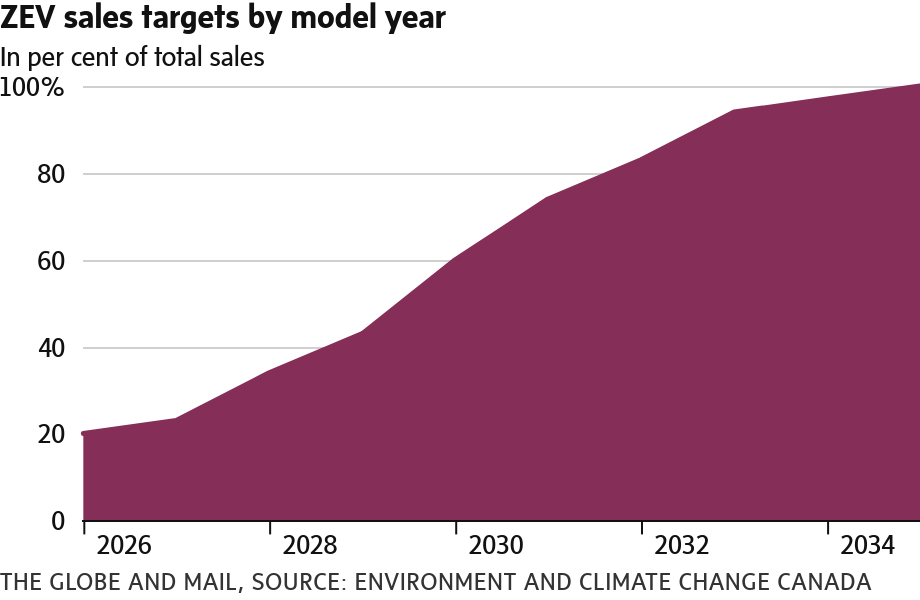

In December, 2022, Ottawa announced its own proposed ZEV targets, citing B.C. and Quebec as evidence that sales targets, combined with incentives, increase consumer choice and will accelerate the transition from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles.

The proposed federal ZEV sales targets would require at least 20 per cent of new vehicles sold in Canada to be zero emission by 2026, at least 60 per cent by 2030 and 100 per cent by 2035.

Market share for ZEVs increased to 8.9 per cent for 2022, up from 5.6 per cent in 2021, according to a February S&P Global report. The Globe and Mail spoke to ZEV owners about why they made the switch and what they would say to others considering doing the same.

When announcing the ZEV targets in December, Ottawa also announced plans to invest in 50,000 EV charging stations across the country, for almost 85,000 federally funded chargers across Canada by 2027. Provincial and municipal governments, along with private-sector companies, are also beefing up charging infrastructure. In B.C. for example, apartments and condos built before Aug. 31, 2021, with no existing EV charging infrastructure are eligible for rebates through a provincial program; some municipalities, including Squamish, offer additional top-ups to that program.

Tackling the charging gap would help make EVs more accessible, says Jeff Turner, mobility director for Dunsky Energy and Climate Advisors. “When we think about whether there is an equity concern about EVs … the affordability issue to some extent will sort itself out, the purchase price of vehicles is coming down, the used market will see more and more EVs over time – the bigger concern is whether or not everyone can benefit from convenience and affordability of charging at home,” he says.

“If you have a driveway and your own home you can probably pretty easily install a charger and benefit from that convenience and affordability. For folks in rental buildings and multi-unit residential buildings, that benefit of EV ownership is a lot less obvious,” Mr. Turner says.

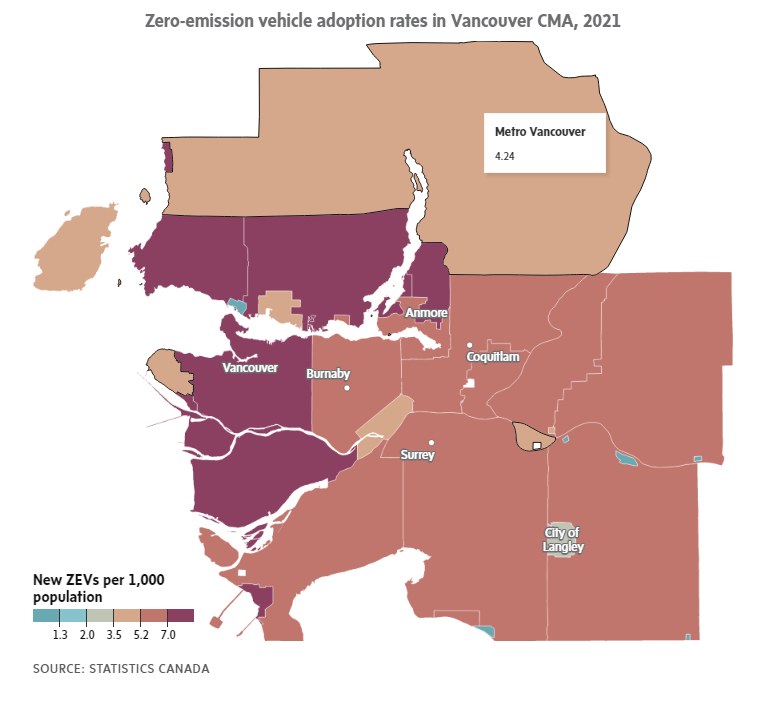

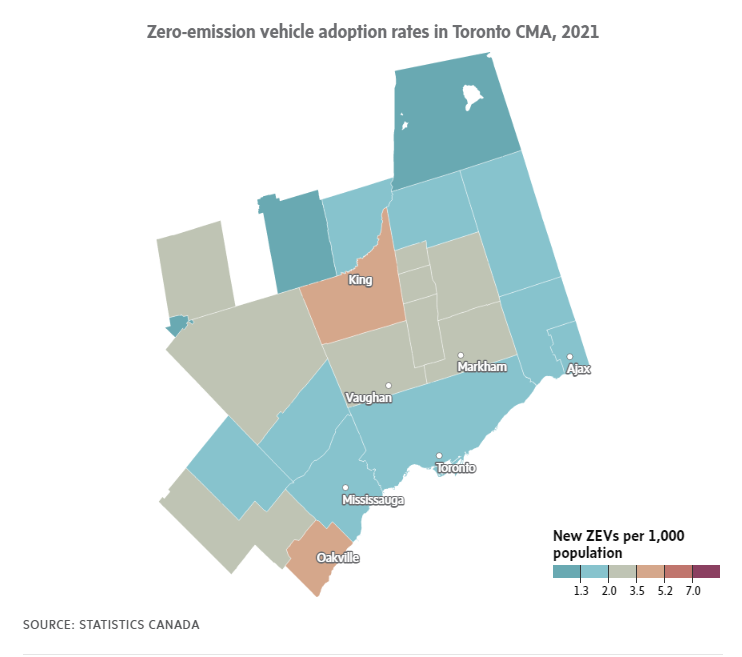

Data show that EV ownership tends to increase along with household incomes. In B.C., for example, one of the highest EV adoption rates – at about 15 vehicles per 1,000 people – was in Anmore, an independent municipality with a population of about 2,500 with a median household income of $162,000. Oakville, one of the most affluent cities in Ontario, has the highest ZEV adoption rate in the province, at nearly four vehicles per 1,000 people.

EV advocates say that pattern should change as the number and types of EVs increase.

Some jurisdictions have tweaked policies to favour lower-income consumers. B.C. last year announced its EV rebate program would take individual and household incomes into account; individuals with income of $100,000 or more are not eligible for EV rebates. The program also has price caps: $55,000 for compact and full-size cars and up to $70,000 for larger vehicles, including trucks.

Cleaner air, a clearer conscience and ready access to charging all played into Greg McKone’s decision to buy an EV.

An information technology manager and climate change advocate, Mr. McKone lives in Abbotsford, east of Vancouver. Motivated by the desire to reduce polluting emissions, he bought a used 2017 Nissan Leaf for $21,000 in 2019. He and his wife used to own two cars; as they worked from home during the pandemic, they went down to one.

A homeowner, he bought a Level 2 charger online for about $200 and had an electrician friend install it in his garage.

He hasn’t noticed a significant difference in his monthly hydro bill, appreciates the cost savings from not having to fill up with gas and likes the thought of doing his bit for better air quality.

His pet peeve? He’d like to see more affordable, no-frill vehicles.

“A basic EV could be such a good price,” he said in a message.

“Instead, EVS are coming fully loaded (heated seats, AC, power steering, stereo, power windows, fancy interiors, self-driving) … I’d like to see a basic EV, something a high-school student could buy for $15,000 – yeah, I’m old, but I can still dream, right?”

Analysts says the federal sales targets should increase variety and ease supply bottlenecks.

“Right now the big challenge we’re seeing is not the fact that Canadians don’t want EVs. They do want them – it’s the fact that they are not able to get their hands on one,” says Ekta Bibra, senior policy adviser with Clean Energy Canada.

“When you start hitting high percentages, [automakers] are going to have to start making vehicles that Canadians want – and not all Canadians want a luxury SUV,” she added.

For the past few years, Dunsky has prepared a ZEV Availability Report for Transport Canada. This year’s report, released in January, found 82 per cent of dealerships in Canada had no ZEVs in stock in March, 2022.

Beyond price and charging options, EV owners consider their work and travel routines along with local roads and weather.

Molie Lalonde lives in Lévis, Que., and shares two electric vehicles – a 2014 Nissan Leaf and a 2019 Tesla Model 3 – with her boyfriend.

Ms. Lalonde used to live and work in Montreal, where she relied on the Metro system and didn’t own a car. When the couple moved to the countryside in 2015, they decided they needed a vehicle to commute to their jobs in Quebec City.

The Nissan Leaf, bought used in 2018, replaced a gas-powered Volvo that was costing them around $300 a month in fuel. But the Leaf’s battery was flagging, reducing the average range per charge from more than 100 kilometres to sometimes less than half that distance, especially in colder weather. They looked at replacing the battery, but were put off by the cost and inconvenience and decided instead to buy a new Tesla, keeping the Leaf as a “just in case” vehicle for short trips.

With a Quebec provincial incentive, the Tesla cost $68,000 when they bought it, Ms. Lalonde says. A database manager for a non-profit organization, she worked primarily from home during the pandemic. Her boyfriend, an engineer, can charge the vehicle at his office and they have two chargers at home. On days they both work in the city, they commute together.

The purchase was a stretch, but aligned with their values and lifestyles, Ms. Lalonde says.

“We looked at our priorities and bought a car that suits us,” she said.

When people ask her about purchasing an electric vehicle, she tells them to consider their driving habits, family schedules and when and where they’ll be able to charge the vehicle.

“For me, because of environmental reasons, I can’t see myself driving a gas car again. It just doesn’t make sense.”

WENDY STUECK, ENVIRONMENT REPORTER

YANG SUN

The Globe and Mail, March 23, 2023