As President Barack Obama unveiled the first major regulations to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions in the United States, his ambassador in Ottawa urged Canada to do the same and take action to combat climate change.

It is a reminder to Prime Minister Stephen Harper of the political challenge he now faces: His chief climate-change policy has been to match U.S. action, but now the Americans are getting more aggressive, and publicly suggesting Canada act too.

U.S. Ambassador to Canada Bruce Heyman, in his first speech since taking office in April, noted the U.S. move unveiled Monday to cut emissions from coal plants by 30 per cent by 2030. And then he called for more action, including on Canada’s fastest-growing source of emissions, oil production.

“We need to continue that work together moving toward a low-carbon future, with alternative energy choices, with greater energy efficiency, and sustainable extraction of our oil and gas reserves,” Mr. Heyman said.

He challenged Canada to join with the U.S. to combat climate change, and said North America’s “newfound energy abundance should not distract us from the need to improve efficiency and combat climate change.

“This is not a task that we can take on individually. It can only be successfully challenged together.”

The message came with no overt linkage to Canadian projects such as the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. Officially, that pipeline is to be judged on whether it would have a net impact on North American emissions. But Mr. Obama has delayed it twice, as activists make it a symbol for the climate impact of Alberta’s oil sands.

Whether they affect Keystone or not, Mr. Obama’s new regulations on coal in the United States are likely to have an impact in Canada.

They could place new cross-border pressure on Canada to cut emissions here, in a crucial sector – oil production.

Mr. Harper has for years pledged to steer Canada’s greenhouse-gas policy close to that of the United States. He has argued that Canada cannot act alone because its economy is closely integrated with that of the United States.

Now, Mr. Obama has put forward a coal proposal that would cut U.S. emissions by about 10 per cent by 2030 – an amount equivalent to all of Canada’s emissions.

In the Commons on Monday, Mr. Harper sought to ensure the comparison between the two countries is about how each treats coal-fired power plants, rather than how each is dealing with greenhouse-gas emissions.

He noted that Canada has already adopted regulations for power plants, and said Mr. Obama is “acting two years after this government acted and taking actions that do not go nearly as far as this government went.”

But coal is not the same thing on either side of the border, noted University of British Columbia professor Kathryn Harrison, an expert on climate policies around the world.

In the United States, “king coal” is the biggest source of emissions. In Canada, coal’s impact is much smaller, and the fastest-growing source of emissions is oil production, notably from Alberta’s oil sands, which will account for 80 per cent of the growth from now to 2020.

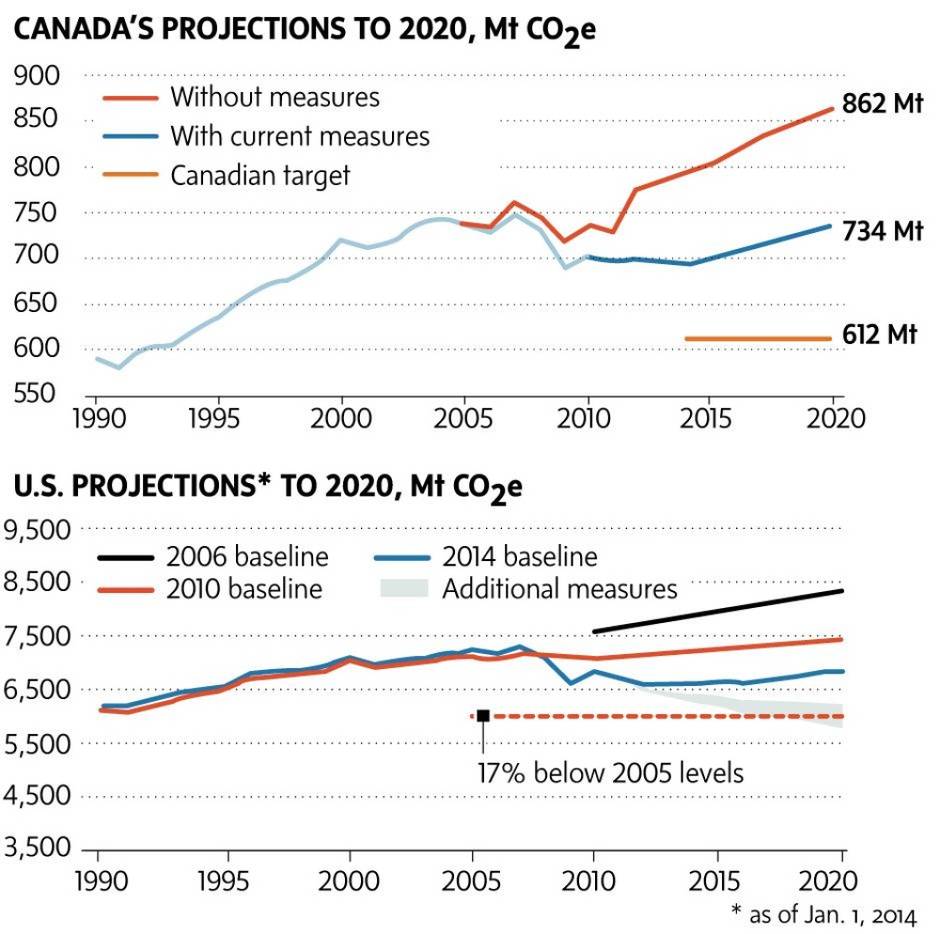

The United States is already far ahead of Canada in meeting its emissions targets.

Both Canada and the United States have committed to reducing emissions to 17 per cent below their 2005 levels by 2020. Even before the new coal policy was announced, the United States was on track for a 7.5-per-cent reduction.

“These regulations won’t get it the rest of the way there, but it will close that gap significantly,” Ms. Harrison said. Canada, however, lags. “We’re projecting emissions are going to go up.”

The Conservative government has pledged since 2006 to issue regulations for Canada’s oil sector, but it has repeatedly delayed them – most recently last December, when Mr. Harper said they would take a few more years.

Now that the Obama administration is acting on coal, it will likely take a more aggressive attitude to new international climate negotiations to be held in Paris next year. And as it attempts to push major emerging economies such as China and India to further action, it could press Canada to do more, too.

At the moment, however, it appears that, apart from possible additional delays for approving the Keystone pipeline, any pressure from Washington is likely to be political, rather than economic.

Canada versus U.S.

CAMPBELL CLARK

OTTAWA — The Globe and Mail

Published Tuesday, Jun. 03 2014, 6:00 AM EDT

Last updated Tuesday, Jun. 03 2014, 6:00 AM EDT