It was early summer, and the rumours were in overdrive. Russian troops had just reinvaded the eastern Kharkiv region of Ukraine and were believed to be massing for another thrust, this time into the northern province of Sumy.

Russian artillery strikes on the Sumy region from across the border in Russia’s Kursk region had increased to the point that they were analyzed by Ukraine’s military intelligence service in June as laying the groundwork for a second assault on Sumy, which Russia invaded and then withdrew from in the first weeks of what is now a 2½-year-old war.

But as Ukraine’s military leadership began making preparations to defend Sumy – increasing the number of troops and equipment stationed in the region – they realized the artillery strikes had been meant to distract them. There was no invasion army on the Russian side of the border. In fact, Russia soon began to draw down the few troops it did have in the Kursk region, leaving only a token force of conscripts to defend it.

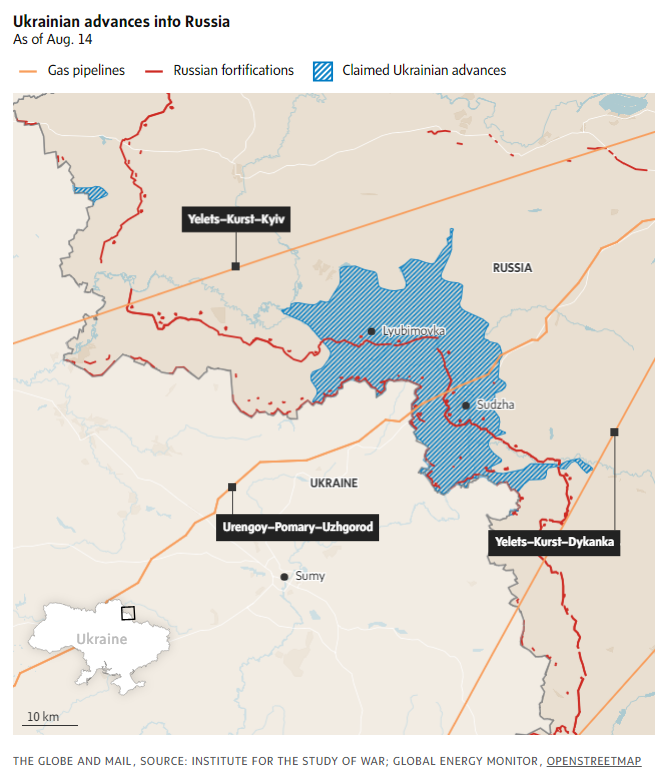

An idea was born. On Aug. 6, a spearhead of Ukrainian troops, backed by light armour and helicopters, sprinted across the border, launching a counterinvasion. The Ukrainian military claims to have captured between 800 and 1,000 square kilometres of Russian territory over the past eight days.

Andriy Zagorodnyuk, a former Ukrainian defence minister who still occasionally advises the government, said Russia had deployed troops to the Kursk region earlier in the summer but withdrew them when it saw the Ukrainian counterdeployment. Afterward, he said, the Russians “started to kind of pay less attention to this area. But in reality, Ukraine was gathering troops, not just to prevent Russia from entering Sumy but actually to start this raid.”

Mr. Zagorodnyuk said he didn’t have direct knowledge of how the Kursk offensive came to be, but other military analysts interviewed by The Globe and Mail also pointed to the sequence of events around the border at Sumy.

The resulting offensive represents the first foreign incursion into Russia since the end of the Second World War. On Wednesday, Ukrainian television broadcast scenes of Ukrainian troops yanking the Russian flag down from a bank that was geolocated as being a few blocks from the centre of Sudzha, a town 13 kilometres deep into Russian territory and a key hub for transiting Russian gas bound for Europe.

It’s a gambit that has flipped the war on its head, at least temporarily, while infuriating Russian President Vladimir Putin. It has also led to questions about Ukraine’s end game in Kursk – and whether a symbolic operation is weakening its chances on the war’s main battlefield, in the southeastern Donbas region.

Right now, however, the operation looks to be a startling success, with Ukrainian troops reportedly digging trenches with the apparent intent of holding on to their newly acquired chunk of Russian soil. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky – whose gambler’s instinct can be seen in the daring operation – used his Telegram channel to taunt his Russian counterpart this week.

“We see how Russia really moves in the times of Putin: 24 years ago, there was the Kursk disaster – the symbolic beginning of his rule; and now we can see what the end for him is. And it is also Kursk. The disaster of his war,” Mr. Zelensky wrote, referring to the accidental sinking of the Kursk, a Russian nuclear submarine, a tragedy that took 118 lives early in Mr. Putin’s long rule. “Russia brought war to others, and now it is coming home.”

Ukraine’s top general, Oleksandr Syrskyi, reported to Mr. Zelensky on Wednesday that his troops had advanced another one to two kilometres since the start of the day and had taken more than 100 Russian soldiers prisoner. In a video conversation broadcast on Mr. Zelensky’s Telegram channel, the Ukrainian President asked Colonel-General Syrskyi to carry out the next “key steps” in the operation. Col.-Gen. Syrskyi replied: “Everything is being executed according to the plan.”

Military analysts see the incursion into Kursk as both an attempt to force Russia to pull units out of Donbas – where its troops have been making slow but steady progress toward the strategic cities of Pokrovsk and Chasiv Yar – to counter the new threat, and an effort to boost flagging public belief in Ukraine’s ability to win the war against its larger neighbour.

But fighting on multiple fronts is a bigger challenge for Ukraine than it is for Russia, which has a much larger army, even as it has been slow to respond to the challenge in Kursk.

“My concern is that Ukrainians will expand this operation so much by deploying additional units from other difficult areas that they will increase the scope of the operation and get nothing from it. They will suffer losses … and this will have a simultaneous impact on the front line in the Donbas,” said Konrad Muzyka, a military analyst based in Poland who has been studying the war for Ukraine since it began.

He said Ukraine would need to carry out a massive mobilization drive if it wanted to be able to defend both Kursk and Pokrovsk.

Mr. Muzyka also touched on remarks from Ukrainian officials suggesting that capturing and holding Russian territory could improve Kyiv’s bargaining position in any future negotiations – breaking a taboo on discussing the possibility that Ukraine could cede land to Russia, which controls about 15 per cent of Ukrainian territory, in any deal to end the war.

Mr. Putin, however, has been talking escalation, not negotiations, since the start of the Ukrainian operation in Kursk, which he said had been carried out with the help of Ukraine’s “Western masters.”

“The enemy will certainly receive a worthy response,” he vowed Monday.

There were reports that he was pressing Russia’s ally Belarus to enter the war against Ukraine under the terms of the mutual defence treaty between the two countries. Belarusian media reported Tuesday that military equipment and ammunition were being transferred to Russian units defending the Kursk region.

Mr. Muzyka said that after almost 30 months of war, there are a limited number of ways that Russia could escalate its campaign against Ukraine. “My concern is that because Russia has no conventional means to respond to this attack, they will just focus on what they think will have a big impact on Ukraine, which is threatening civilian targets and killing non-combatants.”

While Russia prepares its response, Ukrainians are basking in a needed moment of optimism. The Kursk offensive, Mr. Zagorodnyuk said, is a reminder that since Ukraine can’t win a war of attrition against Russia, it must fight back asymmetrically.

“People like it when Ukraine does something out of the box – because that’s, in our opinion, how we’re going to survive.”

Mark MacKinnon

Senior International Correspondent

The Globe and Mail, August 14, 2024