Western governments have struck Russia with an unprecedented barrage of sanctions in retaliation for its invasion of Ukraine, isolating the world’s 11th-largest economy from the global financial system and rendering Moscow an economic pariah.

The measures announced over the weekend by the United States, the European Union and allies such as Canada included freezing the Russian central bank’s foreign exchange assets and barring several banks from the global financial system’s primary mode of communication.

The moves had an immediate effect: The value of the ruble collapsed to a record low on Monday, forcing the Russian central bank to double interest rates, and the government to impose strict capital controls to prevent a full-scale bank run. The Russian stock market stayed closed on Monday, and the value of Russian companies trading on foreign markets plunged.

While NATO countries and their allies have not sent troops to fight in Ukraine, escalating sanctions have effectively become a declaration of financial warfare – even by traditionally neutral countries, such as Switzerland, and those such as Germany and Italy that rely on Russian gas.

In less than a week, Russia has been ostracized from the global economic community. Its ruling oligarchs face sanctions around the world, its largest banks have been cut off from international financial markets, with only some exemptions for oil and gas transactions. Its most important new infrastructure project, the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany, has been shelved.

Much of the country’s $630-billion in foreign exchange reserves was frozen, denying the Russian central bank its main tool for defending its currency. The central bank spent much of the past decade building up these reserves in the hope of making Russia impervious to sanctions. This approach appeared on Monday to have failed, as the G7 countries froze Russia’s overseas assets and made it illegal for commercial banks to transact with the country’s central bank.

Major western companies have begun divesting Russian assets, marking the end of a decades-long corporate rapprochement and reinvestment after collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. On Sunday, British oil giant BP said it would exit from its 20 per cent stake in state-backed oil producer Rosneft. On Monday, Shell said it would end its joint ventures with Gazprom, another state-backed oil producer.

Only a few years ago, Russia was a member of the G8, a group of the world’s most advanced economies, before being expelled over its invasion and takeover of Crimea.

“The conditions for the Russian economy have altered dramatically,” Russia’s central bank governor Elvira Nabiullina said on Monday afternoon as she unveiled measures aimed at preventing the collapse of the country’s financial institutions.

The central bank raised its policy interest rate from 9.5 per cent to 20 per cent in the hope of persuading people to leave their money in the banks. It also introduced a requirement that 80 per cent of all foreign earnings by Russian companies be converted to rubles to prevent energy exporters from sitting on U.S. dollar and euro earnings.

“To our Russian counterparts who are today struggling vainly to prop up a ruble in freefall, let me say: We warned you,” Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said in a Monday news conference, at which she and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau outlined Canada’s latest sanctions.

Effective Monday, Canadian financial institutions are prohibited from transacting with Russia’s central bank or sovereign wealth fund. The other G7 governments announced similar measures, with the goal of preventing the Russian central bank from using its international assets to buy rubles to prop up the currency.

Other sanctions announced over the weekend include plans to eject several Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system – the main global conduit for financial transaction orders – and to freeze the assets of Russian officials and elites. Last week, the Western governments introduced heavy sanctions on financial institutions including Russia’s two largest banks, Sberbank and VTB, and export controls to restrict Russian access to foreign-made technology.

The collapse of the ruble could have severe effects on the country’s economy. A lower foreign-exchange value for the currency makes imported goods more expensive, fuelling inflation and making it harder for companies and the government to repay foreign denominated debt.

Jennifer McKeown, head of the global economics service at Capital Economics, a consulting firm, estimates that Russia’s economy could contract by around 5 per cent this year as a result of the sanctions.

That could have knock-on effects, particularly for European countries that export to Russia. However, any spillover is likely to be small in comparison to the economic downturn in Russia, Ms. McKeown said in a note to clients.

“Russia accounts for only 2 per cent of the exports of even the most exposed major economies in Western Europe. What’s more, financial linkages have fallen sharply since the Crimea crisis in 2014,” she said.

The most substantial impact on the global economy could be rising commodity prices. Russia is one of the world’s largest oil and gas producers, and along with Ukraine, is a major grain exporter. Disruption of supply could drive up global commodity prices.

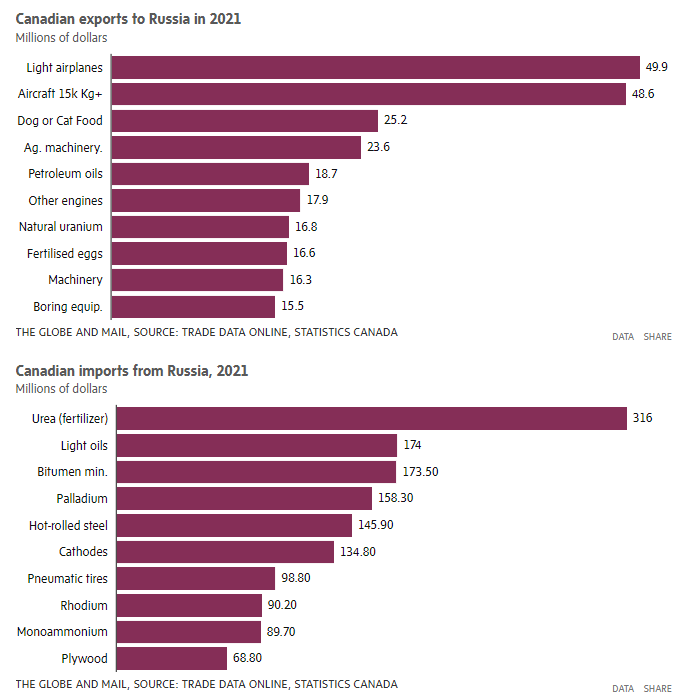

Canada’s trade with Russia is comparatively tiny, but more than $2.7-billion flowed between the two countries in 2021.

Canada shipped nearly $660-million worth of goods to Russia last year, accounting for 0.1 per cent of all Canadian exports, according to Statistics Canada.

High on the list were aircraft, ranging from light airplanes such as small business jets, to passenger jets. Last week, after Canada cancelled all export permits to Russia, Bombardier Inc. said Russia accounts for around 6 per cent of its deliveries of private jets.

The economic measures are already causing major disruptions in Russia. Citizens lined up to get money from ATMS and scrambled to pay transit fares when card payments no longer worked.

“Since Thursday, everyone has been running from ATM to ATM to get cash. Some are lucky, others not so much,” said Pyotr, a St. Petersburg resident who declined to give his last name

Moscow’s department of public transport warned residents on the weekend that they might experience problems using Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay for fares because VTB handles card payments for the metro, buses and trams.

As a sign of Russia’s economic isolation, international trading in ruble-denominated assets essentially ground to a halt on Monday, with investors refusing trades for fear of ending up with frozen assets.

“No one is willing to buy from whoever is selling rubles. So offshore markets are essentially null and void at the moment,” said Simon Harvey, head of foreign exchange analysis at Monex Canada. “It’s what we call a hard stop, basically. You go from a fully functioning market to one that just no longer exists.”

Cristian Maggio, head of portfolio strategy at TD Securities, said that the market environment reminds him of the Russian debt crisis of 1998, or earlier debt crises in Argentina.

“The difference is that those episodes were mostly related to market-driven events. And here we are talking about a political decision whereby, the U.S., the EU, Great Britain, Canada, and a few other Western-aligned countries have decided to impose unprecedented, crippling and co-ordinated sanctions on a country, on a whole economy, and a central bank,” he said.

Ms. Freeland said on Monday that she told Russia’s central bank governor two weeks ago not to let the government go to war.

“The West’s economic sanctions, I warned, would be swift, co-ordinated, sustained and crushing. They are, and they will continue to be,” she said.

Video shows sustained blasts in an area of Kharkiv, Ukraine as the city comes under bombardment by Russian forces.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

MARK RENDELL AND JASON KIRBY

The Globe and Mail, February 28, 2022