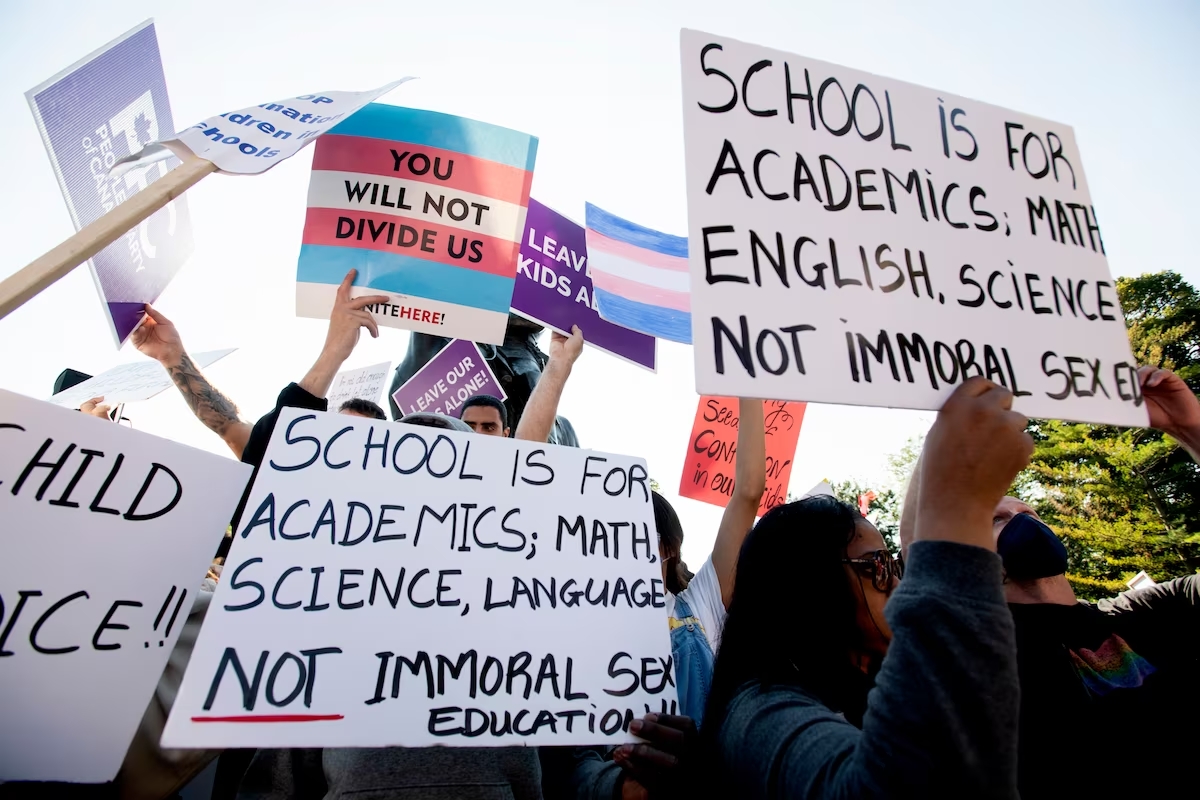

Counter-protesters wave flags beside the Edward VII statue at Queen’s Park in Toronto on Sept. 20. They were there to oppose the 1 Million March 4 Children, a rally against gender-identity education in schools. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Pronoun policies and sex education are just some of the targets of conservative movements that want to control how children learn. Some pupils have other ideas.

Alex Harris, a New Brunswick student, was 14 when he shared that he was trans with the teacher who oversees his high school’s gender and sexuality alliance.

He was nervous to approach his parents – not because he felt unsafe but because he was unsure how they would react.

The teacher guided Mr. Harris as he changed his pronouns and name at school. When he felt ready, she offered to help him speak with his family. Three months later, he told his parents in their living room. They were surprised, he recalled, but adjusted to the change.

“I just needed time. And I needed to know that no matter how they reacted, I had a safe space,” said Mr. Harris, now 17.

Support like this – both from a teacher and parents – can be lifesaving for LGBTQ teenagers like Mr. Harris, who are at an elevated risk for mental health struggles and suicidal thoughts. In this case, the chance to speak with a responsible, trustworthy teacher helped Mr. Harris connect with his family.

Under new rules in New Brunswick, it’s unlikely he’d get this support today. This summer, Premier Blaine Higgs issued a contentious policy that mandates teachers and school staff secure parental consent before using the chosen names and pronouns of transgender and non-binary students younger than 16. This applies to all their classroom interactions and extracurricular activities, as well as name and gender used on all documentation. Previously, schools only needed parental permission to change such children’s names and pronouns in formal record keeping – not throughout their day-to-day lives in school.

While some lauded the pronoun policy for giving parents more say over their children’s time in class, critics have warned the move risks outing vulnerable students struggling in unsupportive homes, as well as those who plan to speak with their parents, but feel unprepared.

Late last month, the Saskatchewan government passed its own controversial pronoun bill into law, which has had the same effect for students under 16. “The default position should never be to keep a child’s information from their parents,” Premier Scott Moe said in support of the new law.

And on Saturday, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith said she will consider legislation that would require similar parental permission over young students’ pronoun and name usage at school. At their annual meeting, her United Conservative Party membership voted overwhelmingly in favour of Alberta implementing such a policy, with Ms. Smith telling them “parental rights and choice in your children’s education” are core principles of her government.

Although Ontario hasn’t followed suit, in September, Ontario Premier Doug Ford opined that teachers and school boards should not “indoctrinate,” adding that students’ gender identity decisions should be flagged for parents.

Parents’ rights protesters at the Sept. 20 rally in Toronto argue with a counter-protester. One is wearing a shirt supporting the 2022 truck convoys; another has an anti-Trudeau flag. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

These new policies and the dialogue surrounding them reflect a growing conservative political movement centred on the notion of “parents’ rights” – an opposition to what some view as overly liberal values taking hold at schools, particularly around gender diversity.

The broad educational shift toward inclusion has met fierce resistance across Republican districts in the United States, where conservative politicians and parents have fought against and silenced classroom discussions about racism, slavery, queer and trans rights. In Canada, the conservative backlash has zeroed in on gender identity and sexual orientation. With many schools now updating their sex-ed curricula, celebrating Pride month, hosting gay-straight alliances and adding gender-neutral bathrooms, conservative groups are pushing back.

Heated school board meetings, student walkouts and campaigns to ban sex-ed lessons, library books and Pride flags have all intensified in recent months, rising to a crescendo with the “Hands Off Our Kids” rallies held across the country in late September.

In one of them, outside the Ontario provincial legislature in Toronto, conservative parents and groups chanting “leave our kids alone” vowed to shield students from what they view as a wave of gender ideology sweeping public schools. Counter-protesters draped themselves in flags – rainbow for Pride, and pale pink, blue and white for trans rights – and denounced the parents’ rights movement as thinly veiled homophobia.

Critics of the parents’ rights camp also see it as a serious overreach into the worlds of students: By insisting that individual parents should get to decide what their own children are taught, what books they can read and what services they can access, the parents’ rights push ends up determining what everyone’s children are learning, reading and accessing at school.

It’s a culture clash that says much about how divided Canadians have grown on the very purpose of school: Should it be a mirror of home, or a telescope beyond it?

At Queen’s Park on Sept. 20, counter-protesters hold up blue, white and pink transgender flags amid signs supporting the 1 Million March 4 Children and a far-right political party. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Saleema Noon, who has taught sexual health education in British Columbia for 25 years, said parents’ misgivings are at an all-time high.

As sex ed is a part of B.C.’s curriculum, schools across the province frequently request workshops from Ms. Noon’s organization, Sexual Health Educators, whose staff is often paid for by parent advisory councils.

A decade ago, some parents began voicing concern when her team raised the topic of sexual orientation during the workshops. Today, it’s ratcheted up to aggression and harassment.

“Words like ‘groomer,’ ‘indoctrination’ and ‘pedophile’ are being thrown around and directed at us. I don’t remember anything like that years ago,” Ms. Noon said.

She rattles off accusatory questions she’s gotten from parents in recent months: Will she be bringing puberty blockers to elementary schools? Will she tell their children they can quietly have a “sex change”?

Ahead of every elementary school sex-ed session, her educators host a virtual, 90-minute workshop for parents to quell exaggerations and rumours about what they’re teaching. Even so, parents are opting their children out of sex ed in record numbers.

“Given the topic I teach, parental involvement is important,” Ms. Noon said. “But it’s a slippery slope. Parental involvement and parental rights – that doesn’t equal parental control. I try to help parents understand there are lots of things about our kids’ lives that we can’t control as they grow up.”

Ms. Noon sees her role as working alongside parents to get the ball rolling with uncomfortable but critical conversations. As she sees it, she provides the science at school, and parents provide the values at home.

Ms. Noon sees adults wrapped up in heated political debates failing to acknowledge the effect on students.

Jonah James attends a Catholic high school in Newmarket, Ont., where he finds the parents’-rights movement to be a worrying sign of diminished trust in educators. CHRISTOPHER KATSAROV/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In Ontario, after a motion to raise a Pride flag at the office of the York Catholic District School Board spawned weeks of angry exchanges between trustees, teachers, parents and high-schoolers – with the board consequently voting against raising the flag – many students felt disillusioned and staged walkouts in protest.

“It definitely left a taint,” said Jonah James, a senior student trustee in Grade 12 at a Catholic high school in Newmarket, Ont. “School is supposed to prepare kids for the future, and we know our future is going to be a more inclusive one.”

Mr. James, 16, said he is troubled that the parents’ rights movement erodes trust toward educators: “I feel bad because, to me, I see parents who are scared because they hear all this villainization of schools.”

In New Brunswick, Mr. Harris says the new pronoun policy is having a chilling effect for LGBTQ students. In the past, he would occasionally overhear slurs in the halls but could generally “fly under the radar.” This fall, he’s noticed the tenor at school becoming more openly hostile, with more glances in the hallways and expletives behind his back.

As for the adults who are celebrating the new policy, he thinks their position is influenced by misinformation. “Most of the time they haven’t actually met a trans kid themselves, and they don’t seem to understand what being a trans kid entails,” Mr. Harris said.

“It doesn’t entail anything abnormal … I have hobbies and interests. I like photography and I like writing, just like any other kid. I’m in extracurricular programs, like yearbook, just like any other kid.”

His mother, Jessica Harris, cringes when she hears the words “parental rights,” saying the movement doesn’t represent her values.

In the moment her child came out to a teacher, he needed someone he could talk to whom he felt comfortable with; it didn’t mean he thought less of his parents, Ms. Harris said. She worries New Brunswick’s pronoun policy will mean the most vulnerable students will have fewer people to confide in.

“We need to give the kids a lot more dignity, and a lot more trust.”

Merrit Johnson is a queer 16-year-old in Fredericton who sees how the language of ‘parent rights’ is used against young people and breeds distrust. CHRIS DONOVAN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Through their middle- and high-school years, students begin exploring who they are and who they want to be. Today’s generation of high-schoolers is well-versed in conversations about gender identity and LGBTQ inclusion, coming of age after the legalization of same sex marriage, alongside a popular culture that embraces queer and trans celebrities. With more visibility for LGBTQ people, more youth feel safer coming out.

One in 100 Canadians ages 20 to 24 identified as transgender or non-binary in the 2021 census. Among millennials and Gen Z, the proportion of trans and non-binary people was three to seven times higher than it was among Gen Xers, baby boomers and older generations.

At the same time, rates of depression and suicide remain high among LGBTQ teens. Two in five transgender and non-binary youth considered suicide, with one in 10 attempting suicide, according to a 2021 Trans PULSE Canada study, which also found one in five avoided school, fearful of being outed and harassed.

High schoolers engaged in the current debates over student choice and parents’ rights said they view school as a place that should expand minds, not close them.

“School is a place for kids to be independent from their parents, to learn to think critically, to see different identities, religions and people – and sometimes, to hear viewpoints they and their parents might disagree with,” said Merrit Johnson, a Grade 11 student in Fredericton.

The 16-year-old, who is queer, sees growing wariness among students toward parents seeking an outsized say over what happens at school.

“A lot of the students I’m around are aware of the term ‘parent rights’ and realize how it’s being used against us,” Ms. Johnson said. “All this breeds distrust between kids and their parents, which is the opposite of what these parents want.”

She described her own mother and father as very supportive. This fall, she’s been working with her school’s gay-straight alliance, lining up students, teachers and guidance counsellors to help kids who risk being outed through her province’s new pronoun policy.

“Strict parents don’t typically have good relationships with their kids,” Ms. Johnson added. “When you trust your child, you can form a better relationship where they can come to you, tell you things and view you as a safe person. Once those parents realize this, the whole idea of parents’ rights sort of falls apart.”

Alex Ash sees fear and uncertainty in New Brunswick students this fall. Mx. Ash is executive director at Chroma NB, a community organization in Saint John that’s been helping LGBTQ high school students and teachers navigate the new pronoun policy.

Mx. Ash, who is trans non-binary, said it’s typical for young people to come out to friends at school before their parents because there’s less risk of rejection: “It’s much more scary to come out to someone who is so important to you.”

To Mx. Ash, the words “parental rights” signal discomfort. With some parents, this unease can be talked through and family relationships mended. With others, like those who hoisted homophobic placards in sight of kids at the September protests, Mx. Ash doesn’t mince words.

“This is bigotry veiled as a concern,” they said. “It’s people feeling emboldened to spew their hatred in schools.”

In an era of highly involved, hands-on parenting, anxieties have only mounted for families emerging from three years in a destabilizing pandemic. Many witnessed troubling changes in the mental and emotional well-being of their children, pandemic aftershocks that raised parents’ antennae toward schools.

For Saskatoon mother Nadine Ness, a general mistrust of schools took root during the global health crisis.

Ms. Ness founded Unified Grassroots, a socially conservative group she formed with a handful of parents concerned about pandemic public health measures, including proof-of-vaccine mandates. Today, the group numbers in the thousands and had the ear of Premier Moe when Ms. Ness relayed their fears in late 2021.

The mother of four prefers the term “parental authority” over “parents’ rights.” She’s pushing for more parental say in the public school system, especially over sex-ed lessons and pronoun changes.

“I think a lot of parents, when they’re bringing their issues forward to the school board, to the teachers, it’s not being listened to. They’re being called bigots … they’re being attacked. It’s not taken seriously,” Ms. Ness said.

Her teenage daughter suffers from severe anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and was considered a high risk for suicide after the first pandemic school year in 2020. Ms. Ness and school staff worked together on a plan to keep her safe.

She wants to see a similar collaboration between parents and school staff when students wish to change their pronouns, because these students, too, are at higher risk for suicide. Ms. Ness added she doesn’t like the prospect of teachers and vulnerable students having a “secretive relationship,” as she views it.

Ms. Ness believes school discussion about gender identity and sexual orientation is being driven by activists. She added that sex ed should be “fact-based, health-based and biology-based,” and that conversations about gender identity – or “gender ideology” as she calls it – confuse children and fail to align with values held in many homes.

The Saskatchewan government appears responsive to parents like her: Along with the stringent new pronoun policy, the province has also paused sexual health educators with external organizations from teaching sex ed at schools. The move has also halted sexual abuse prevention experts from speaking to students. Experts stress that’s worrisome in a province with some of Canada’s highest rates of sexual assault and interpersonal violence, the country’s second highest adolescent pregnancy rates, plus heavy caseloads of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

People pass a school in Toronto’s Thorncliffe Park neighbourhood, in the former riding of Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne. In 2015, a backlash against her government’s new sexual-education curriculum led some parents to withdraw children from school. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Between the duelling camps of parents, students and educators sits a neglected group in the middle – mothers and fathers who aren’t ideological, but unsure and apprehensive in the face of a rapid culture shift on gender diversity, according to Lauren Bialystok, an associate professor of educational ethics at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Prof. Bialystok cautioned against writing middle-ground parents off.

“You have to build in time for parents to be able to come to things in a way that makes sense to them. Nobody ever changed their mind because somebody called them bigoted. That’s not how people learn.”

Missing from much of the debate, Prof. Bialystok said, is an education for adults.

“This is a project of not just asserting, ‘This is what we’re doing now,’ but teaching about it, answering questions, showing the evidence for it, showing why this is supportive of kids’ well-being.”

In 2015, former Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne went through that process after her government re-introduced a modernized health and physical education curriculum that her predecessor shelved five years earlier.

Hundreds of parents who were opposed to the updated sex-ed lessons withdrew their children from school in the Thorncliffe Park neighbourhood of her Toronto riding.

Ms. Wynne, the province’s first openly gay premier, said her government tried to dispel the misinformation shaping their opinions: “We had to do it school by school, and by principals meeting with families.”

The Thorncliffe Park principal sat down with each family to explain the new curriculum, painstakingly bringing children back into the public school system with a sanitized lesson plan that for Grade 1 students, for example, would not teach proper names for genitalia.

Ms. Wynne said that while parents should play a role in children’s education, parental involvement can’t come at the expense of student safety.

She views the parents’ rights movement as the latest iteration of social conservatives finding a way to capitalize on parents’ anxieties, with the end goal to strip all discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity from education.

Ms. Wynne, shown in 2017 during her premiership, says she had to work ‘school by school’ to dispel misinformation about the sex-education curriculum released in 2015. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In New Brunswick, Mx. Ash wants to see more avenues for parents and school staff to be able to talk through their fears around these issues. They pointed to No for Now: Guidance for School Staff on Supporting Transgender Students and Parent-Child Relationships – a resource compiled by education experts and social workers focused on LGBTQ students – as well as Beyond Acceptance, a virtual group for parents and caregivers struggling with children coming out. In these sessions, trained educators, health care professionals and parents of queer and trans children help families repair their relationships.

But with the school environment so fraught now, many educators specializing in gender and sexual health have shifted their focus to community groups. Mx. Ash floated the idea of joint sessions hosted by queer community groups alongside long-established organizations with deep experience in schools, such as the United Way, Big Brothers Big Sisters Canada and Boys and Girls Club of Canada.

Ultimately, Mx. Ash says, the most powerful breakthroughs for parents struggling with these issues often come from spending time with LGBTQ people, face to face: “To actually sit down one-on-one to humanize the situation, that’s where I’ve seen the biggest movement.”

And that’s where students have already taken the lead.

In the rural community of Walkerton, Ont., Tristan Kim, 16, has seen students at his high school come out and be accepted by their classmates. He feels a growing disconnect between what happens within the walls of schools and what conservative politicians and some parents have come to believe.

“I personally don’t feel like my school board is indoctrinating me at all,” said Mr. Kim, president of the Ontario Student Trustees’ Association. “Our schools aren’t shoving a bunch of this down our throats or anything.”

He understands that parents want their children to learn the basics in school. Still, for him, education extends beyond math, science and English; it’s also meant to challenge and enlighten young people through exposure to ideas outside their own experience.

Mr. Kim sees students rising above the noise, naturally accepting differences: “It’s very chill.”

CAROLINE ALPHONSO, EDUCATION REPORTER

ZOSIA BIELSKI

The Globe and Mail, November 6, 2023