Canada’s inflation rate hit a 31-year-high in April as prices continue to rise from the grocery store to the gas station. But what, exactly, is inflation and how long will it remain at record highs? A breakdown of everything you need to know.

Over the past few months, the term “inflation” has been unavoidable. From rising prices at the grocery store and buying gas to paying for rent and mortgages, it’s gone from being an economic concept to one that’s felt with every purchase. There can hardly be a household in Canada that hasn’t already felt staggered by inflation’s effect on most aspects of daily life.

But what, exactly, is it? Why is inflation driving up the cost of living in Canada and how does raising interest rates solve the problem? Here’s a breakdown of everything you need to know about the big I.

What is inflation and how is it calculated?

Inflation is a decline in the value of money – hence why $100 doesn’t go as far today as a decade ago.

The country’s main measure of inflation is the Consumer Price Index, which Statistics Canada calculates every month. CPI is comprised of a basket of goods and services, weighted by how people actually spend their money. For example, housing costs account for about 30 per cent of CPI, because the typical household allocates a large portion of its budget toward those costs; on the other hand, clothing and footwear is generally a smaller expense, accounting for 4 per cent of CPI.

Statscan tracks how the price of all goods and services in the CPI basket change over time, and ultimately, how that factors into the overall inflation rate. A lot of factors affect prices – how difficult a product is to find, the cost of labour and the raw materials used to make it, and competition among the places selling it, to name a few.

According to the Bank of Canada website, policies that stimulate economic growth can also cause inflation. For example, when people have more money, their demand for products and services can rise, and that can pull up prices.

CPI shouldn’t be confused with a cost-of-living index. Such an index measures the cost of maintaining a standard of living. Also, because the CPI basket is based on average household spending, it doesn’t always reflect an individual’s experience. For example, the escalating price of meat might not be relevant to vegetarians.

What is Canada’s current inflation rate? How does it compare historically?

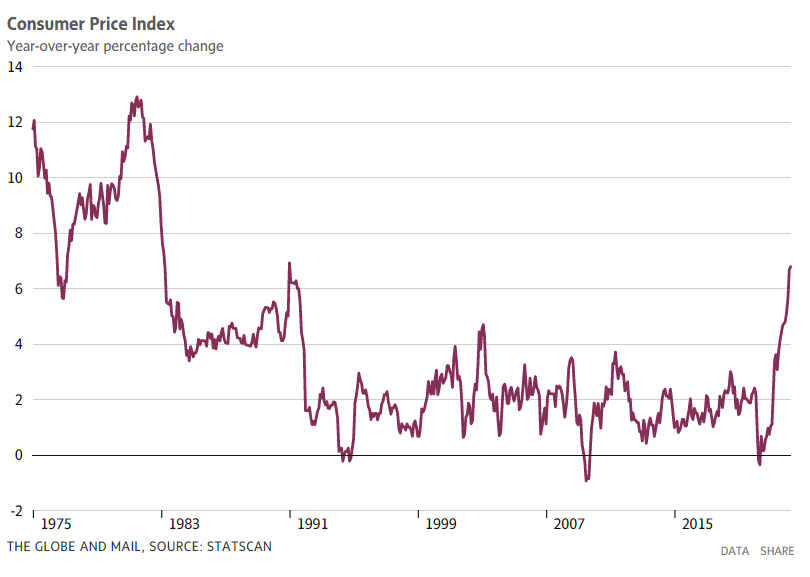

Canada’s inflation rate hit a 31-year high in April. Statistics Canada said the Consumer Price Index rose 6.8 per cent in April from a year earlier – a percentage point higher than March’s rate, 6.7 per cent. It was the highest rate since January, 1991, when the federal goods and services tax took effect, and the latest in a string of troublesome reports.

From a broader historical perspective, inflation was north of 10 per cent in the mid-1970s and again in the early 1980s. In the early 1990s, when the Bank of Canada formally adopted maintaining low and steady inflation as its primary monetary policy objective, inflation still hovered around 5 per cent. But since the central bank set its inflation target at 2 per cent in 1995 – using interest rates to help steer inflation toward that rate – inflation has averaged very close to that target.

Why is inflation so high in Canada?

Several factors are driving the inflation run-up, including persistent supply chain disruptions and the Russia-Ukraine war, which has pushed up commodity prices. Also, as COVID-19 public-health restrictions ease, people are unleashing their pandemic savings in service industries such as travel, and the increase in demand is contributing to the price surge.

How does inflation affect the cost of living?

The price of seemingly everything is on the rise, and steeper inflation is getting tougher for Canadians to avoid.

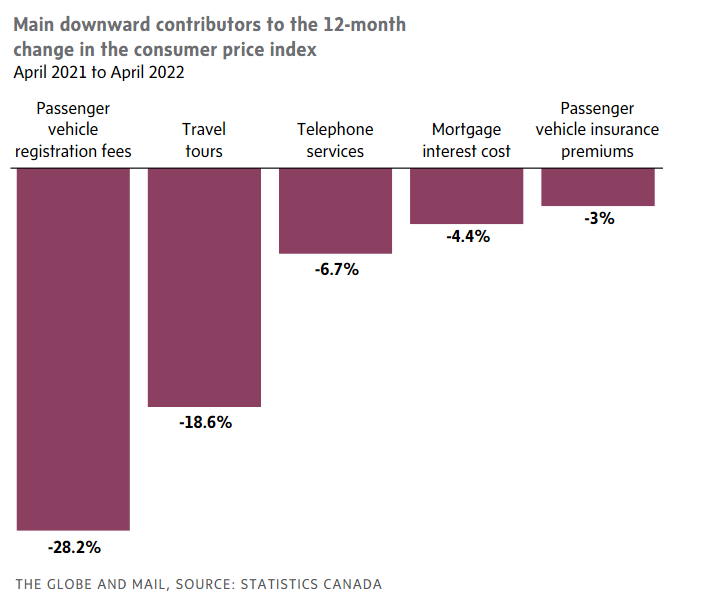

In March, Statistics Canada said that around two-thirds of goods that make up CPI are experiencing annual price gains of more than 3 per cent, such as gasoline (39.8 per cent), shelter (6.8 per cent) and household appliances (9.4 per cent). In April, consumer prices rose 0.6 per cent.

Which items have been most affected?

- Gas prices: Gasoline prices fell slightly in April, although were up 36 per cent from a year earlier. Average national prices are now hitting close to $2 a litre and likely to push higher.

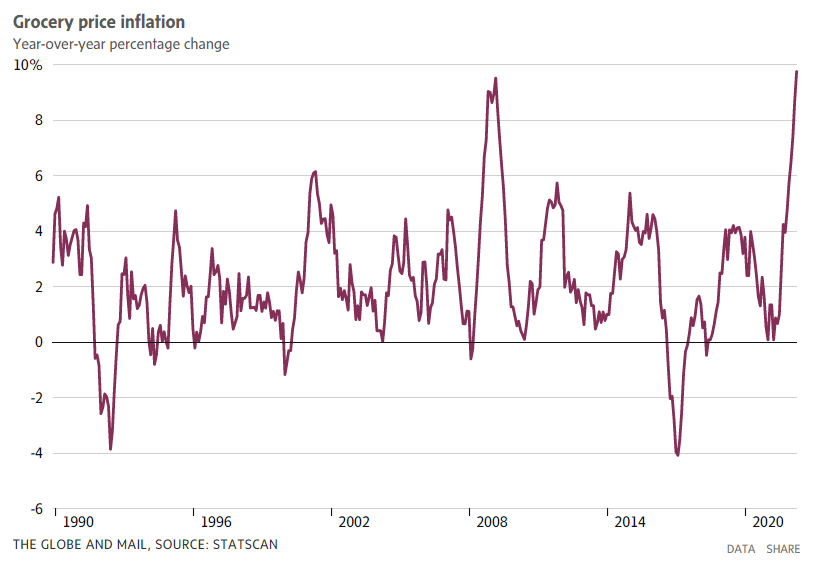

- Groceries: Households paid nearly 10 per cent more for groceries in April – the steepest annual gain since 1981. Over the past year, the price of pasta has risen nearly 20 per cent, fresh fruit by 10 per cent and coffee by around 14 per cent.

- Meat: The price of meat was up 10.5 per cent in March compared with the same month in 2021, with prices for fresh or frozen beef up a staggering 14.1 per cent. Meanwhile, a recent study from Dalhousie University found that meat alternatives – like faux burger patties or plant-based “chicken” nuggets – remain an average of 38 per cent more expensive than meat.

- Household appliances: Refrigerator prices have jumped 23 per cent over the past two years, while washing machines and dishwashers have risen 11.5 per cent.

- Lunch: Buying a soup and sandwich now costs nearly $18 on average, up 24 per cent, according to data from digital payments company Square. A hamburger costs $10.86 – up 26 per cent. And an average salad costs $12.63 – up 25 per cent.

- New homes: Canada experienced a 25.7 per cent drop in the number of homes sold over the last year and a 3.8 per cent slide in housing prices between March and April, the Canadian Real Estate Association said. The average home price last month totalled $741,517. Economists say, however, that Canada’s housing market is cooling and predict that home prices will fall as much as 20 per cent this year.

- Additional home costs: Shelter costs rose 7.4 per cent in April, the highest in nearly four decades, due in part to sharply higher prices for energy to heat homes. Rents rose 4.5 per cent in April, with larger gains in Ontario and British Columbia.

Inflation is also picking up in pandemic-hit sectors. The cost of restaurant meals rose 5.4 per cent over the past year, up from 4.7 per cent in February. Traveller accommodation prices soared 24.4 per cent on an annual basis, while air transportation jumped 8.3 per cent in March alone.

What will bring inflation down?

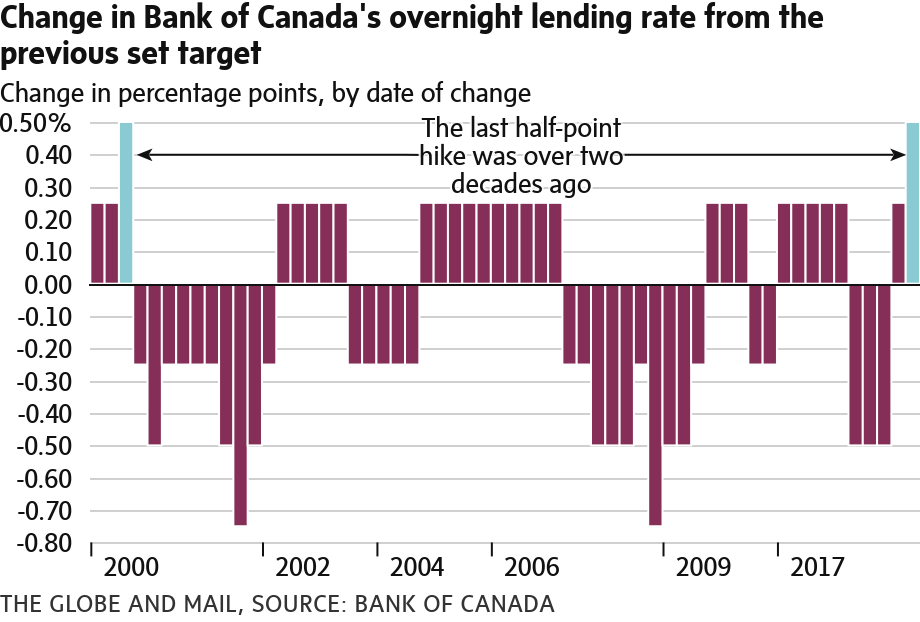

Time and interest rates are considered the biggest weapons to slow inflation. The Bank of Canada has been moving aggressively to rein in inflation by hiking interest rates. In April, the central bank raised its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point to 1 per cent – the largest increase at a single decision since 2000. It usually raises rates by a quarter-point. Several more rate hikes are expected over this year, including at its next decision on June 1, and into 2023.

The Bank of Canada aims to keep inflation close to 2 per cent to keep a stable currency, but the rate has now exceeded the bank’s target range of 1 per cent to 3 per cent for a full year. That streak is expected to last a while longer with the central bank expecting inflation to average more than 5 per cent in 2022.

How does raising interest rates curb inflation?

Interest rate increases theoretically bring down inflation by prompting banks to increase interest rates on deposits, loans and mortgages. Higher interest rates encourage saving, and discourage borrowing and spending. In response, companies increase their prices more slowly or even lower them to encourage demand. This reduces inflation. Higher interest rates also work to reduce demand for goods and services, which makes it harder for companies to raise prices.

It also makes borrowing more expensive. That means higher interest rates for mortgages, home equity lines of credit, credit cards, student debt and car loans. Borrowing rates for mortgages and other loans are rising quickly, a source of potential stress for households carrying debt.

“Rising interest rates are designed to slow the economy by making borrowing more expensive. That tends to slow sectors like housing,” Bank of Canada deputy governor Toni Gravelle said in a speech on May 12. “But this slowing might be amplified this time around because highly indebted households will face high debt-servicing costs and will likely reduce household spending more than they would have otherwise.”

Are wages keeping up with inflation?

In short, no. Around two-thirds of Canadians have seen inflation outpace their wage gains over the pandemic.

In April, the average hourly wage rose 3.3 per cent on an annual basis – much lower than inflation – meaning, the average worker is seeing their purchasing power decline, a trend in place for several months. Inflation-adjusted wage growth was negative in many parts of the labour market, including industries tied to the public sector – such as education and health care. Meanwhile, Canada’s job growth slowed substantially in April, adding only 15,300 positions last month.

“We’re just not seeing wage gains anywhere near the rate of inflation,” said David Macdonald, senior economist at the CCPA. “It may be that workers have yet to catch up to the fact that inflation is high, and that they should start asking for higher wage gains on a year-to-year basis.”

How long will inflation remain high?

A key concern among economists is that Canadian consumers and businesses – who negotiate wages and set prices, respectively – expect inflation to remain high for the next two years, according to Bank of Canada surveys, which could keep CPI on an elevated path for some time.

The stakes are high for the central bank, which is looking to keep inflation expectations in check and guard its reputation as the steward of low and stable inflation.

“We have a full-on inflation issue, and the central banks need to play catch-up, with haste,” Bank of Montreal chief economist Doug Porter recently wrote to clients.

GLOBE STAFF

The Globe and Mail, May 18, 2022