The North is melting five times faster than it was before 2005, with alarming implications for global sea levels, Indigenous people and Arctic ecosystems.

Three glaciers converge on Ellesmere Island, as seen from the air in 1957. Climate change has taken an increasingly large bite out of Arctic ice in recent decades. RCAF

When federal scientists working in the High Arctic began monitoring a glacier on Meighen Island in the 1960s, they built a wooden hut for shelter.

As the years passed and snow accumulated, the hut was gradually buried and then abandoned once it became easier to build a new one atop the one becoming entombed in the glacier. Another decade or so and a third hut was constructed on top of the other two. It was a vivid demonstration of the principle that glaciers grow from the top and spread out at the edges.

Then, climate change kicked into high gear across the North. The warming that had already been stunting the growth of Canada’s Arctic glaciers by the 1990s now rapidly overwhelmed and reversed it.

In 2012, the warmest Arctic summer recorded in modern times, all three of the huts emerged from the ice like a rickety wooden tower standing precariously atop the melting glacier before toppling over. In one season, more than half a century of accumulated glacial history on Meighen Island had simply trickled away.

Remote and inaccessible, Canada’s High Arctic glaciers – the most extensive in the world after those of Antarctica and Greenland – are performing a disappearing act largely without an audience.

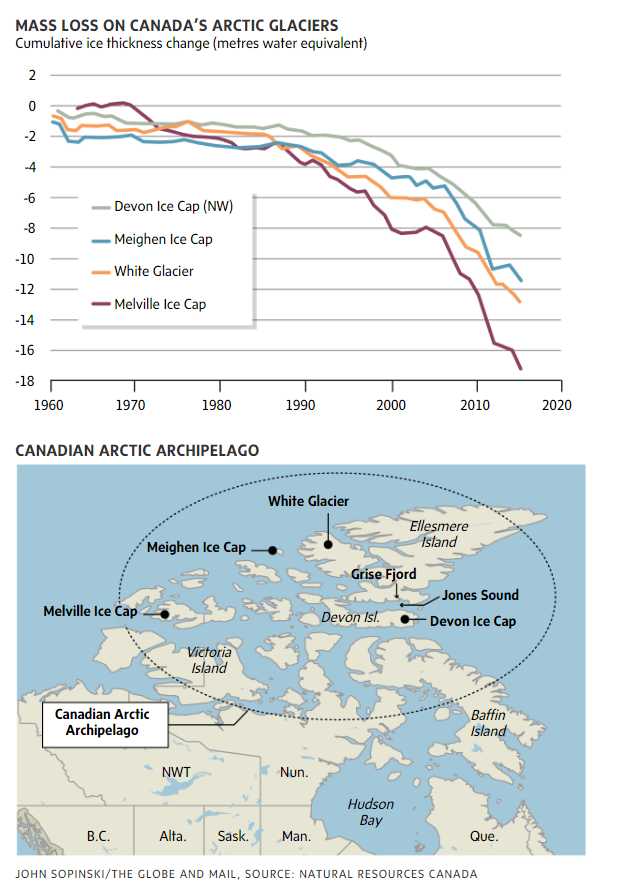

Measurements reveal that the change is accelerating. The current rate of glacial melting in the region is now five times what it was before 2005. The exposed huts show that nothing like this has happened since scientists started monitoring the glaciers. Ice cores reveal that the melting rate today is unprecedented in the past several thousand years.

“It’s shocking to see the numbers,” said David Burgess, a research scientist who leads Canada’s national glaciology program. “There’s a lot of variability from year to year, but the long-term trend is quite apparent.”

The process is of global interest because Canadian glaciers contribute to sea-level rise. But there is also local interest. Many of Canada’s Arctic glaciers reach down to the sea and come into contact with tidewater. Scientists are trying to understand what the increased melting means for marine life in the region and for Indigenous communities tied to the ocean.

Dr. Burgess has helped launch a three-year project to monitor the waters of Jones Sound, which separates Ellesmere and Devon islands and receives meltwater from glaciers on both. Together with colleagues he spent a month travelling around the sound in a chartered sailboat this summer gathering marine samples and other clues to recent environmental change in the region.

In Grise Fiord, Canada’s northernmost village, residents described the retreat of a nearby glacier by a kilometre or more in one generation. One question the project hopes to answer for community members is how the increase in freshwater inflow may affect plankton, fish and, ultimately, the location and abundance of marine mammals such as ring seals, a traditional food source.

In the near term, the higher volume of meltwater is enriching northern coastal waters with certain minerals that could alter the profile of species there. Meanwhile, as some of the smallest glaciers and year-round ice patches vanish on the land, local sources of water are lost from what is otherwise a near-desert landscape.

For scientists, the challenge is capturing all the complex effects of climate change happening at the same time and understanding their relationships well enough to make reliable predictions about what is in store for the region.

Maya Bhatia, a biogeochemist at the University of Alberta who leads the project, says Northerners are now on the front lines of an epic change that will ultimately have consequences for the entire globe.

Dr. Bhatia stresses the need for a clear-eyed understanding of what greenhouse gas emissions are doing to the planet, but says she resists deploying apocalyptic language when it comes to climate change.

“What I say to my students is that I have no doubt the world will survive,” she said. “The problem is we may not like what we’re going to get.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, October 30, 2019