New data show the split in annual earnings between men and women persists in Canada, Tavia Grant reports. If the trend isn’t addressed, long-term drawbacks for our economy will be unavoidable.

It may be 2017 and Canada may have a self-proclaimed feminist as Prime Minister, but gender parity is not yet the norm in Canadian workplaces.

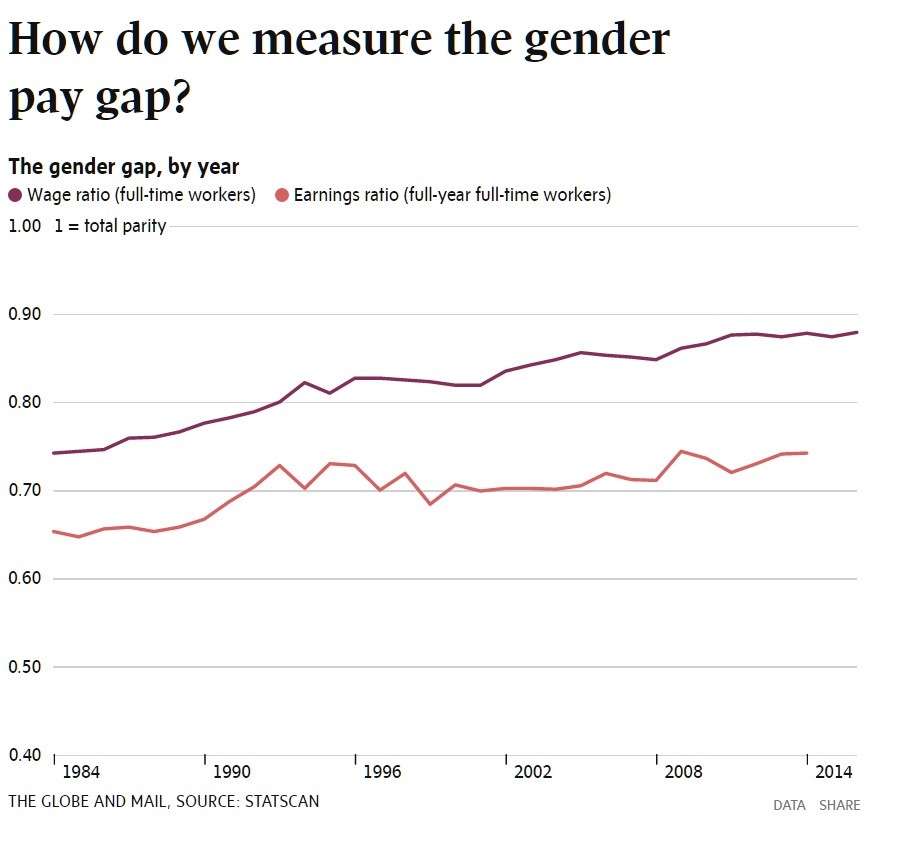

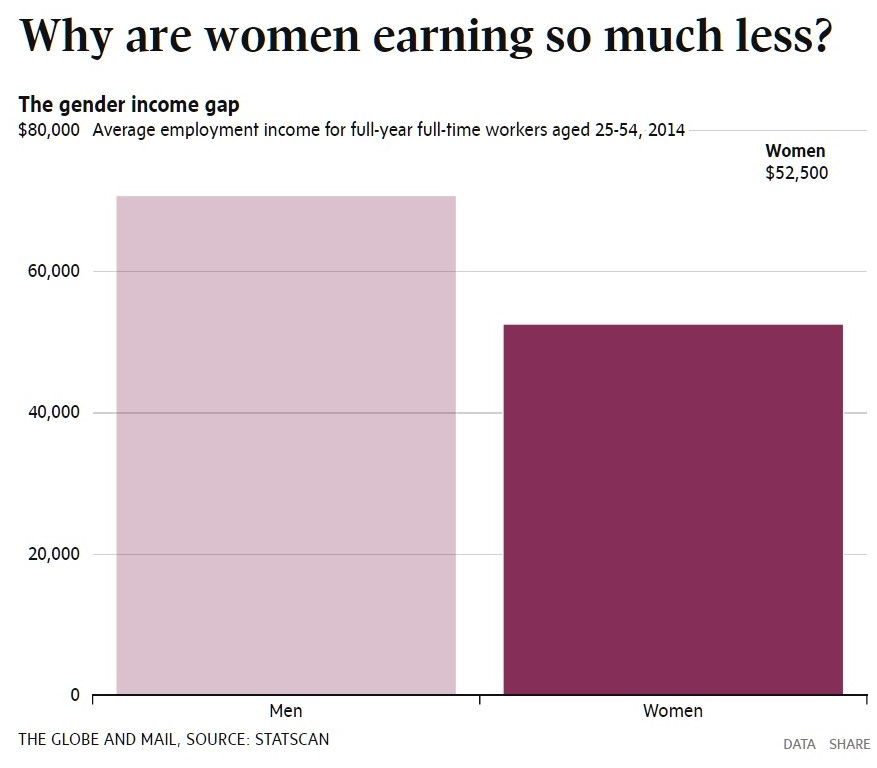

Recent annual data show that, in yearly earnings, women working full time in Canada still earned 74.2 cents for every dollar that full-time male workers made. Another measure that controls for the fact that men typically work more hours than women – the hourly wage rate – shows women earned 87.9 cents on the dollar as of last year.

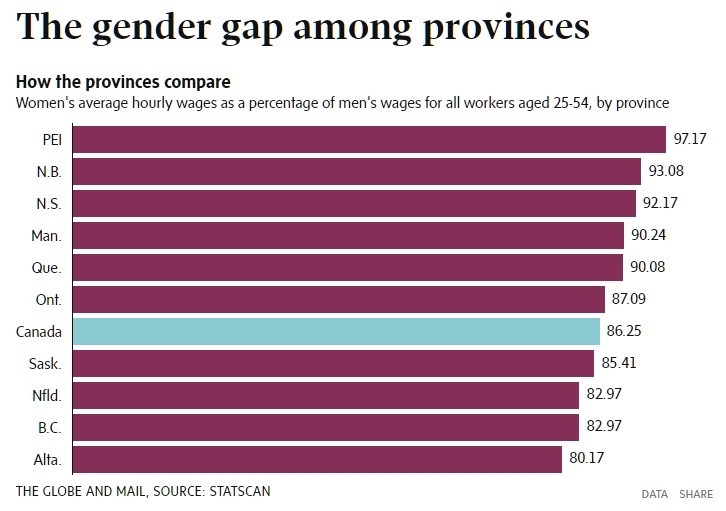

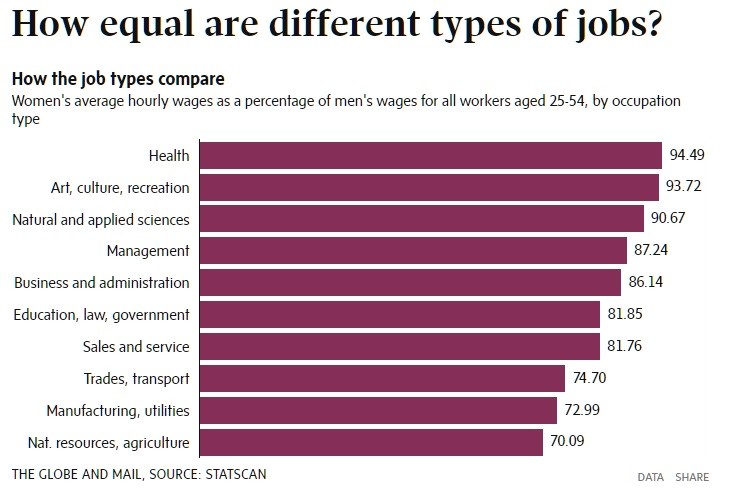

The updated numbers, compiled from Statistics Canada data, show the pay gap exists in every province and in every major occupational group, though there are variations. The gap in annual earnings between men and women has barely budged over the past two decades, even as education levels among women have surpassed those of men.

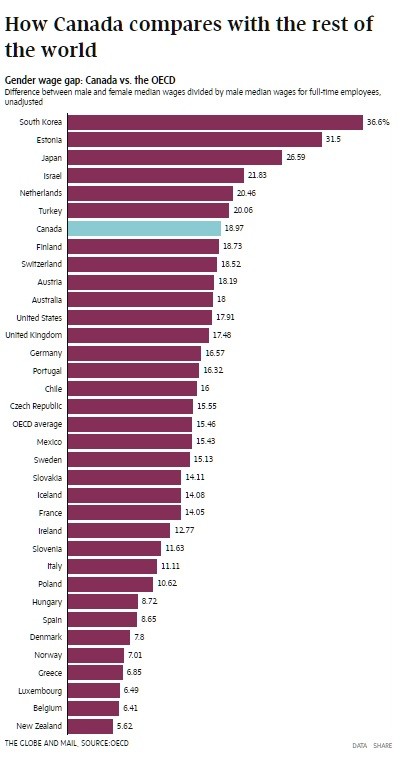

Canada’s gender pay disparity is larger than the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development average. Canada has also tumbled down the World Economic Forum’s global gender gap rankings, to 35 th place, from 19th place two years earlier.

“We’re kind of stuck,” with regards to the pay gap, said Sarah Kaplan, director of the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, who calls the persistent gap “outrageous.”

It also carries long-term consequences. Depriving women of equal pay hurts their ability to save. With longer life expectancies, this means they are living longer on reduced retirement income, Prof. Kaplan said. As well, “if you pay women less than men, they feel devalued in the workplace. They’re more likely to drop out of the workplace. You then lose a productive worker in an economy where we’re desperate for talent … There are plenty of economic reasons why we should have equal pay.”

Progress on women in the workplace has been “disappointing,” says a report to be released Monday that grades the federal government on efforts to advance women’s rights and gender equality.

The scorecard, by Oxfam Canada, released ahead of this week’s International Women’s Day, assesses the government in eight areas. It scores well in representation – creating Canada’s first gender-balanced cabinet and restoring funding for women’s rights advocacy. More should be done to address violence against women and the unequal distribution of unpaid work, the report said.

The area where least progress has been made is in jobs and pay equity – addressing the unequal economics of women’s work.

“It’s disappointing because the government’s overall focus on gender equality and inclusive growth would lead you to believe that this would be an area of priority,” said Lauren Ravon, Ottawa-based director of policy and campaigns for Oxfam. “This is an area where it can really make a difference in women’s lives. If we’re not tackling issues of access to work and poverty, it’s very hard to make progress on other fronts for women.”

There are different ways to calculate gender-pay ratios. A broad measure – of annual earnings among full-year, full-time workers – shows women earned 74.2 cents for every dollar a man earned in 2014. This measure reflects the overall financial well-being of families.

That said, men working full time tend to work more hours than full-time women, which explains some of the gap. Economists often use hourly wage rates as another basis of comparison. This shows the rate for women was 87.9 cents for each dollar a man earned in 2016. Annual earnings disparities haven’t changed over the years, while hourly wage gaps have gotten smaller.

The hourly wage gap in most provinces and occupations has narrowed. It also looks smaller when other factors, such as field of study, are factored in.

But it doesn’t close completely, Prof. Kaplan said. Even with these adjustments, there is still a gap.

“Some people say, 4 or 5 or 6 cents, that’s hardly anything, that’s like the gap went away. Let me tell you, compounded for an entire career, that is a huge difference in the amount of money people will have saved for retirement, and will be able to use to support their families … And by the way, it still matters – why would you want to be paid less than the person sitting next to you?”

Several factors explain the pay differences. One is that women are more likely to work part time than men, in many cases because they take on child-care and elder-care responsibilities. They are also more likely to experience work interruptions in their careers.

Another reason is the types of jobs that people do. Jobs that are heavily female, such as cashiers and daycare workers, tend to be lower paid than many jobs that skew heavily male, such as truck drivers or construction workers.

Another factor is discrimination, or unconscious bias, where “men and women are doing exactly the same job, but women are just valued lower,” Prof. Kaplan said – for example, among lawyers, where the male partner is paid more than the female partner.

Economists refer to the “unexplained” component of the wage gap as the part that can’t be explained by differences in productive characteristics, and which could be from discrimination or other factors.

Canada is higher than the OECD average in its gender pay gap, ranking as the seventh most unequal of 34 industrialized countries.

At the current rate of change, the global economic gender gap won’t be closed for another 170 years, the World Economic Forum says. Canada has also tumbled down the forum’s global rankings, to 35 th place, due to factors such as wage equality, earned income and the share of women in Parliament.

Other countries are taking steps to boost wage transparency. As of April, Britain will require large employers to publish, on their websites, annual calculations showing how large the pay and bonus gap is between their male and female workers.

Australia has established a Workplace Gender Equality Agency, which publishes detailed regular statistics on the pay gap. Large firms are now required to report gender-pay gap data to the agency.

Across Canada, gender parity at all levels in the workplace “improves profitability, workplace culture and the economy as a whole,” PwC noted in a study last year. It estimated that Canada would likely see $105-billion in GDP growth if it closed the wage gap and boosted female work-force participation.

Its assessment of how women in the labour market are faring, compared with in other countries, shows “room for improvement,” in areas such as increasing awareness of the pay gap and offering supportive polices and working arrangements.

“The gender pay gap remains wide, and closing it should be a priority for businesses and governments across Canada,” it said.

Internally, PwC has introduced a target that by 2020, half of its new partners in Canada will be women, up from less than a third now, Montreal-based PwC partner Stéphanie Leblanc said.

Among occupations, health care has the most even hourly wage rates between men and women, while the biggest disparity is in natural resources.

Despite higher levels of education and more access to the work force, “ women’s efforts to build a better life are hampered by the unequal distribution of unpaid work, the gender barriers to many fields of work, the undervaluing of jobs held predominantly by women, and the often unspoken social norms that offer men higher wages and rates of promotion from the moment they enter the work force,” the Oxfam report said, noting that pay gaps are even greater for racialized and Indigenous women.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail, Employment Minister Patty Hajdu said her government is committed to making “meaningful differences” in the gender wage gap.

This means programs to encourage women to join “non-traditional” fields, such as the trades, and enhancing data to better understand the “unexplained” portion of the wage gap. “There are many actions that our government can take, and that all levels of government can take to change outcomes. But there is that societal piece as well. We have to better understand how we influence that societal piece – there are very strong stereotypes and stigmas that still exist to this day,” Ms. Hajdu said.

TAVIA GRANT

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

LAST UPDATED: MONDAY, MAR. 06, 2017 7:45AM EST