Entrepreneurs aren’t yet back at anywhere close to the level of activity we saw before COVID-19.

Ten days into the first pandemic lockdown, already an eternity for thousands of Canadian business owners forced to shut their doors, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau used one of his daily televised updates to “speak directly to small businesses and entrepreneurs”, expressing what would become a hopeful and recurring sentiment in the ensuing months.

“Canadians are counting on you, and I am counting on you to, come back strong from this,” he said. “No matter what comes next.”

What came next, starting in the latter half of 2020, was a surprising economic recovery. As vaccines rolled out the following year and restrictions lifted, employment soared and consumers went on an unprecedented spending spree, helping Canada’s economy outperform all its G7 peers over the last year.

But not everyone came along for the ride. Entrepreneurs aren’t back, at least not at anywhere close to the level of activity we saw before COVID-19, and the evidence is mounting that the ability of someone with a good idea to launch a business, support themselves with it and build wealth for their families and their communities is much harder than it used to be.

Toronto’s Yonge St. is lined with closed shops in March 2021, amid another COVID-19 lockdown. Canadian small businesses, particularly those in Ontario, faced some of the longest COVID-19 restrictions in North America. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The pandemic blew a hole through the entrepreneurial class in Canada as it shuttered businesses and spooked would-be self-starters. At the same time, the crisis accelerated major economic forces that were already working against small business owners: growing corporate concentration among businesses’ competitors and suppliers, the rising cost of living, and an exodus of seasoned business owners.

The result is an economy at risk of growing ossified, one in which the business dynamism that comes with high levels of innovation and entrepreneurship slips away.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. A number of surveys over the past two years painted a picture of a pandemic boom in entrepreneurship unfolding in Canada.

A poll released by the Royal Bank of Canada in 2021 found 55 per cent of Canadians aspired to own their own business, a four-year high. A survey released by Intuit, a tax software company, and picked up widely by the media claimed one-quarter of Canada’s businesses had been launched since 2020, involving a whopping two million Canadians. Not to be outdone, FreshBooks, an accounting platform for small businesses, claimed seven million Canadians were preparing to quit their jobs to be their own bosses.

This was all ostensibly good news for an economy on the mend. Entrepreneurship and new business formation are key pillars of employment and economic growth, laying the groundwork for innovation and better living standards. That’s made all the more important by Canada’s bleak productivity outlook. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development predicts Canada will post the weakest GDP per capita growth – meaning economic output adjusted for population growth – over the next decade, the slowest pace of any advanced economy.

Yet it’s become clear that many of those aspirations either withered away, or reflected side hustles, like Etsy shops and food delivery gigs, and not the launch of new productive businesses that create jobs for others.

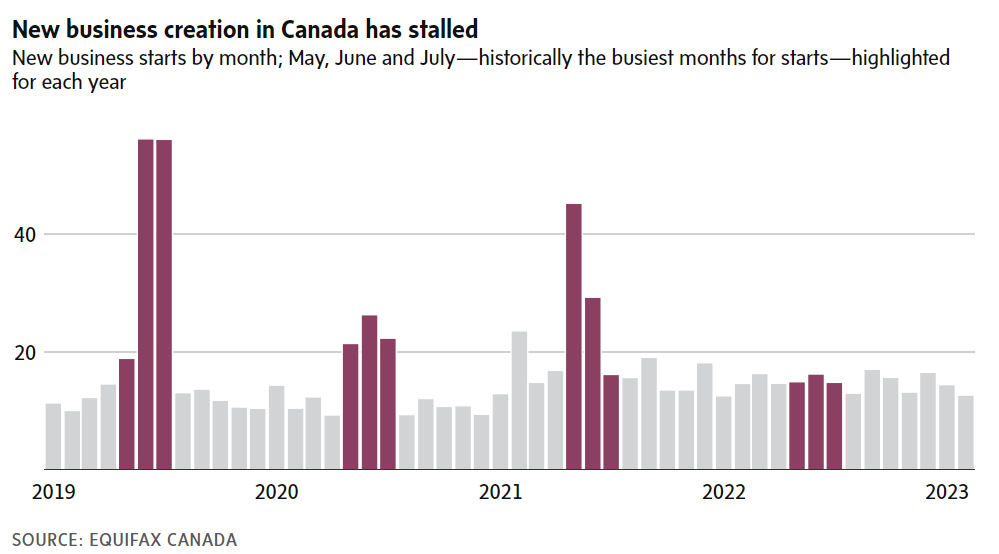

The gap can be seen in business openings data compiled by Equifax Canada, the credit rating agency. The busiest months for business starts are typically May, June and July, yet openings during those months haven’t come close to matching what was seen in 2019. A rebound that began in 2020 and then picked up pace the following summer completely fizzled last year, with new openings in the second quarter down by half from the year before.

This year the outlook for new business openings is shaping up to be similarly grim, said Jeff Brown, head of commercial solutions at Equifax, with month-over-month business starts during the first quarter slumping for the first time in two years.

“2019 was a high-water mark and there’s no way we’re going back to that this year, especially with inflation and the high cost of capital,” he said. “Those are strong headwinds for entrepreneurs trying to start a business.”

There’s no question large swaths of the business sector have rebounded from pandemic lockdowns, albeit with deep scars to show for it. Statistics Canada’s own measure of the number of operating businesses, which tracks the natural process of businesses opening and closing their doors, launching and failing, returned to its prepandemic level by the end of 2021 and has generally continued to rise since, albeit not at the same pace the population has grown.

But the Statscan numbers also show that excluding sectors like education, health and social services the business opening rate – new openings as a share of enterprises already open for businesses – has been trending down since, falling in March to the lowest level since April, 2020.

“Entrepreneurs find opportunities no matter what, but I do think there’s a general feeling across Canada that people are in a holding pattern before taking on additional risk,” said Doug Adlam, a Guelph, Ont.-based serial entrepreneur who, in late 2020, sold a mortgage industry-focused fintech he co-founded, before launching Gambit Wealth, a corporate wealth and tax planning firm geared to other entrepreneurs.

Mr. Adlam rhymes off the myriad questions entrepreneurs are faced with: the fate of the housing market, job markets, interest rates, even the very nature of what it means to run a business in a world rapidly being reshaped by artificial intelligence. “Put all that together and for a lot of people I think there’s an increased amount of uncertainty and risk in starting a business today than there was in the past,” he said.

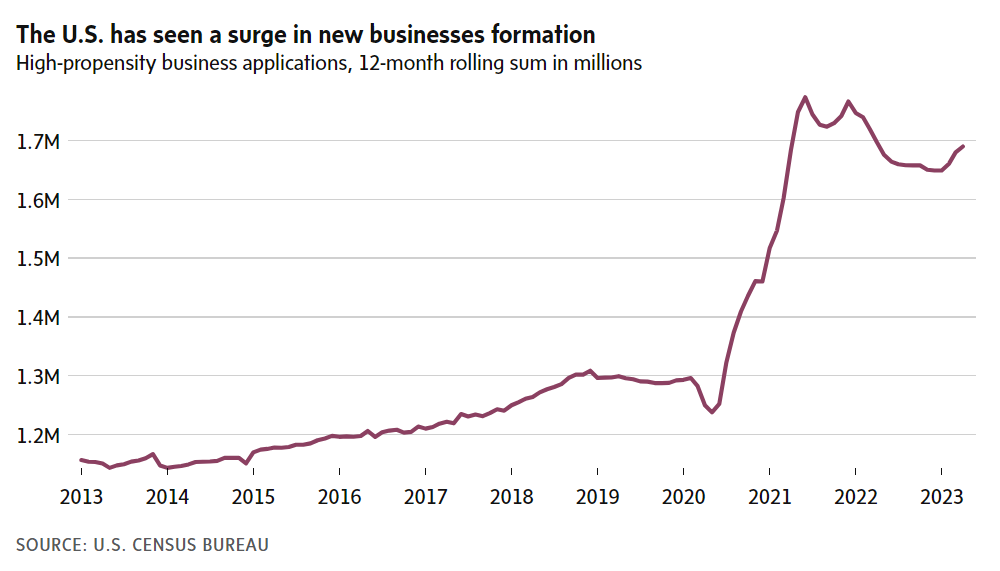

The picture is markedly different south of the border, where a start-up surge that began during the pandemic shows little sign of slowing.

Direct comparisons to Canadian data are difficult to make, but one oft-watched indicator of entrepreneurial activity can be found in the number of high-propensity business applications tracked by the U.S. Census Bureau, which reflect start-up plans that have a high likelihood of turning into active, hiring businesses.

After modest growth in the decade prior to the pandemic, a period that saw much hand-wringing in the U.S. about depressed entrepreneurship levels, the number of applications soared by the middle of 2021 and remains 30 per cent higher than before COVID-19 hit, despite anxiety about the stability of the U.S. banking system and the prospect of an economic downturn.

The start-up boom likely stems from a combination of factors, like the widespread disruptions to how people shop, work, live and spend, rising household wealth from government supports, and people reflecting on their lives amid the lockdowns, said Kenan Fikri, director of research at the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington, D.C.-based bipartisan policy organization.

At first, economists thought the effect might be ephemeral, however business applications showed to be broadly based across industries and states, and subsequent data have begun to confirm the trend. “If the pandemic era we just lived through has delivered a lasting, positive shock to American entrepreneurship, that can only be good for the U.S. and ensure a stronger recovery,” he said.

Likewise, Canada has lagged the U.S. on another barometer of entrepreneurship: self-employment, and more specifically, the self-employed who have incorporated their businesses. Those ventures tend to be larger, riskier, have greater demand for capital and, importantly, are more likely to employ others.

In Canada it took until earlier this year for that form of self-employment to reclaim where it was at the same time in 2019, on a non-seasonally adjusted basis. By comparison, in the U.S., incorporated self-employment is up nearly 12 per cent over the same period.

This all raises a question: Why has the rebound in entrepreneurial activity been weaker in Canada than the U.S. when the two countries generally experienced similar headwinds and tailwinds over the last three years?

Perhaps it’s because Canadian small businesses, particularly those in Ontario, faced some of the longest COVID-19 restrictions in North America, or because America’s fiscal response was more focused on direct payments to households, providing more of a cushion for people to start businesses. Maybe it’s simply that in good times the U.S. consistently outmatches Canada on business investment, boosting productivity and scaling startups into world-beating companies, so it makes sense that in periods of adversity those gaps would be even more pronounced.

But it’s also true that Canada’s recovery has been far more reliant on public sector hiring than in the U.S., with federal, provincial and municipal governments adding more net new government workers since February, 2020 than the entire U.S., despite its much larger population. As self-employment has fallen, the public sector’s share of the job market is near its highest level in three decades and holding, suggesting that for at least some Canadians faced with the choice of pursuing a risky venture versus the security on offer from an expanding government sector, they’ve opted for the latter.

Canada was well positioned to take full advantage of the opportunities the pandemic presented.

We regularly score very high on rankings of startup activity. In its most recent report for 2021, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, an international research project that conducts standardized surveys of people across 50 countries, found Canada once again placed first among G7 countries for total early-stage entrepreneurial activity, meaning the launch of nascent businesses – even if Canada’s rank slips when it comes to how many of those ventures survive at least 3.5 years.

The business shutdowns and mass layoffs that came with the lockdowns also severed the connections many people had with old jobs that may not have been fulfilling to them, but which they stayed at out of habit or necessity.

What’s more, until inflation reared its head, the cost of borrowing money was at record lows, with governments, agencies like the Business Development Bank of Canada, and others eagerly extending credit to existing and new businesses to help the private sector get back on its feet.

“In the early months of the pandemic, we were flooded with applications because I think a lot of people were not able to work at their main businesses, so it felt like the right time to write a business plan,” said Karen Greve Young, chief executive officer of Futurpreneur, a non-profit startup booster backed by the BDC. While she still sees a strong community of entrepreneurs, “there probably are fewer people just throwing their hat in the ring for the sake of it.”

One big reason lies in the glut of help wanted ads, and not just for all those new government jobs. Amid high inflation and soaring job vacancies, employers offering hefty paycheques – and a considerably less-stressful lifestyle than entrepreneurship entails – hoovered up many workers who might otherwise have ventured out on their own, particularly in the tech sector.

“Some people whose heart and soul may be in entrepreneurship couldn’t refuse the offers they were getting in traditional employment,” said Kevin Sandhu, a Vancouver-based tech entrepreneur and investor who recently launched Otter, an artificial-intelligence driven fintech providing banking, accounting and legal services to the self-employed.

Kevin Sandhu, a Vancouver-based tech entrepreneur and investor who recently launched Otter, an artificial-intelligence driven fintech. ALISON BOULIER/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

At the same time, remote work arrangements offered by many companies provided people “the freedom and flexibility to control their own schedules that historically were reserved for entrepreneurship,” he said.

Now those forces that might have once lured people away from trying their hand at entrepreneurship are fading. For one thing, a growing number of companies pressure their workers to return to the office.

But more than that, recent large-scale layoffs in the tech sector mean an era of cozy employment is likely over, and if history is any indication, some of those who receive pink slips will pursue their own startups.

It’s a scenario familiar to those who’ve watched tech booms come and go. Alumni of failed Ottawa tech giant Nortel Networks launched 165 companies, according to data and information site Crunchbase, while former employees of BlackBerry, the vastly shrunken Waterloo tech company, founded nearly as many. The near demise of Nokia in Finland likewise sparked an entrepreneurship boom in that country.

“From a talent perspective and the kind of people we want to have creating companies, we arguably haven’t been in a better position than we are in a number of years,” said Viet Vu, manager of economic research at The Dais at Toronto Metropolitan University.

But if that seems to suggest Canada is on the cusp of an entrepreneurship renaissance, not so fast.

“We’re seeing a mixed environment where financing is hard to get, but we might have more people willing to start companies,” said Mr. Vu. “The result could be a fewer number of entrepreneurs starting those companies, but they might be of higher quality.”

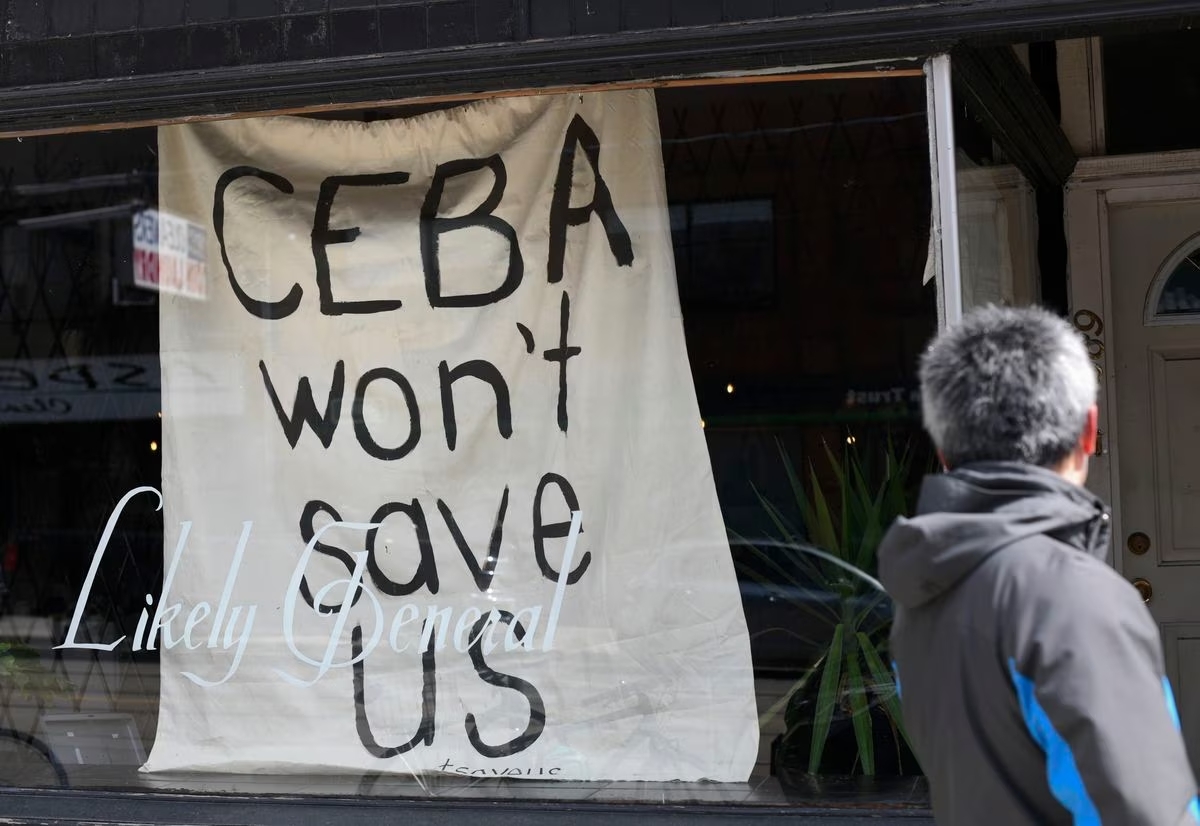

A sign in the front window of Likely General, a store in Toronto, reads “CEBA won’t save us,” in reference to the Canadian Emergency Business Account (CEBA) support program introduced in April 2020. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

That March, 2020, entreaty which Mr. Trudeau delivered to entrepreneurs and small businesses was accompanied by the announcement of a new support program, the Canadian Emergency Business Account. Amid the COVID-19 flare-ups and stalled reopenings that followed, more than 900,000 businesses took on $49-billion in CEBA loans, interest free until their repayment date.

That already-extended deadline is the end of this year, however according to Statistics Canada, $40-billion in CEBA loans were still outstanding as of March 31. A recent survey from the CFIB suggests less than half of recipients say they’ll be able to repay the loans on time. The CFIB has asked the federal government to extend the deadline again.

Little wonder then that as interest rates rose over the last year, so did the level of anxiety felt by business owners. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s quarterly survey on business conditions reported that in the second quarter of this year, 45 per cent of owners struggled with soaring borrowing costs, the highest reading since 2009.

To get by, small businesses are increasingly turning to credit cards to keep the lights on, according to Equifax, with credit card debt up 15 per cent over last year, and lines of credit up 11 per cent.

“We’re seeing revolving credit card debt on the small business side that’s kicking the can down the road,” said Mr. Brown, who worries some businesses are banking that interest rates will fall again. “Hope is not a plan,” he said.

One reason for the increase in credit card usage is that access to other types of capital is becoming more restrictive. In the first quarter business lending conditions were at their tightest level since the second quarter of 2020, according to the Bank of Canada’s senior loan officer survey.

For many entrepreneurs and small business owners, frustration with accessing capital in Canada is nothing new. Compared to other countries, Canadian banks extend a below-average amount of small-business loans, with just 12 per cent of business loans going to small- and medium-sized businesses, according to 2020 data from the OECD. The OECD average is 44 per cent.

Sam Ibrahim, president of the Toronto-based human-resources firm Arrow Group, said getting funding from a Canadian bank has been a challenge since he founded the company in 2007. “I only knew ‘No’, I never heard yes,” he said.

He said the company’s big break came in 2016 when it expanded into California, and he got eight figures in financing from the Bank of America. He said he got another infusion of capital from J.P. Morgan & Chase Co. in 2021 that has allowed Arrow to expand even further. “I had to go to California to get the funding I needed. I couldn’t get it here, I couldn’t get it in Canada,” he said.

Canadian banks argue access to capital is not a problem. The Canadian Bankers Association said business customers have an 80-per-cent loan approval rate, according to their data, and the amount of lending to small businesses rose 3.6 per cent over the last year. “Where there’s demand, lenders will meet the demand,” said Alex Ciappara, the industry group’s vice-president and head economist, adding SMEs have roughly $100-billion in unused credit available to them.

One thing that might loosen up lending in Canada would be the implementation of an open-banking system with new rules that give consumers and entrepreneurs more control over their financial data. Proponents argue that would make it easier for new, innovative companies to operate in the financial sector. With more companies in the industry, there would be more competition for offering products, such as loans.

The Liberals promised in the 2021 election to introduce open banking by early 2023, but there have been delays, with no clear updated timeline for its implementation.

Behdad Karimi Dermeni is one entrepreneur advocating for open banking. Mr. Dermeni left his accounting job in 2021 to focus fully on his fintech startup ReInvest Wealth, a robo-accounting service that uses artificial intelligence to help small businesses with their bookkeeping and taxes.

He has signed up nearly 100 clients so far but says he is running into roadblocks because of the oligopoly in Canada’s financial-services industry. Banks are making it tough for his clients to connect their accounts to his software and he isn’t able to connect to the digital infrastructure banks use to process tax payments with the Canada Revenue Agency.

“The longer this is postponed, the harder it is for startups to succeed or stay in business,” Mr. Dermeni said.

Against the backdrop of a deteriorating financial picture, Canada’s entrepreneurial class faces another challenge that has only grown more obvious over the last three years: the rising age of many entrepreneurs themselves. And it’s not yet clear to what extent the upheaval of the last few years will dissuade the next generation of self-starters.

The problems predate the pandemic, and much of the demographic data on entrepreneurship does too, but it was already clear that fewer young Canadians have been taking on business ownership over time. According to Statistics Canada, in 2004, 53 per cent of the owners of small- and medium-sized businesses were under the age of 50. By 2020, it was 38 per cent.

There is a significant difference in attitude between generations of entrepreneurs, too. A survey conducted by the Business Development Bank of Canada in February suggested younger entrepreneurs were more likely to seek help for their mental health – but perhaps in part because their mental health was worse.

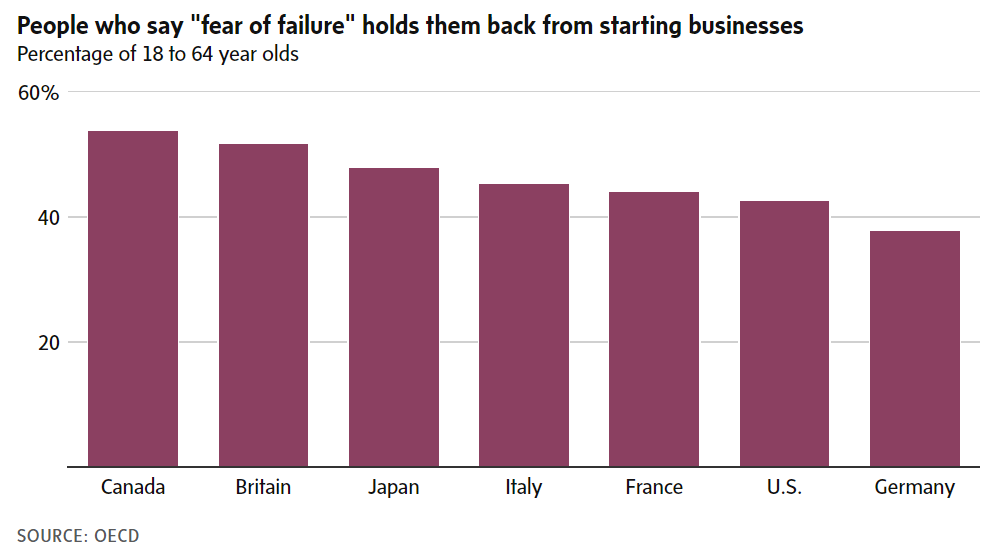

Entrepreneurs under 45 years old reported being more worried about work-life balance, a fear of failure and anxiety over decision making than the older cohort. For example, 48 per cent of younger entrepreneurs reported “fear of loss/failure” being a source of stress, while only 35 per cent of older entrepreneurs felt so.

As it turns out, Canadians now lead all G7 countries in citing “fear of failure” as a roadblock to being an entrepreneur, according to the OECD, having moved up from fifth spot five years ago.

“When you’re a younger entrepreneur, bearing the cost of the decisions you make, and with all the ramifications and the potential consequences – it is taking a toll on them,” said Annie Marsolais, chief marketing officer and mental health advocate at BDC.

Seasoned entrepreneurs who have endured a lot to build their businesses are also increasingly asking themselves if they want the same stress for their kids. CFIB president Dan Kelly said he’s noticed this change over three decades of advocating for small businesses.

“In the past, business owners would ask the question: Which of my three kids do I want to leave the business to?” he said. “And now, I’m hearing more and more often from business owners, that I don’t want my three kids to have to go through the same hell that I did.”

As a result, many small businesses are on the sales block. The good news is that’s providing a way for would-be entrepreneurs to pursue their dreams of business ownership without the ordeals involved with starting from scratch.

Alison Anderson, a Saskatchewan-based entrepreneur whose company SuccessionMatching.com connects buyers and sellers of businesses, feared that when the pandemic hit, ready buyers would vanish. The opposite happened, with the number of potential buyers signing up to the service growing five-fold in the first year of the pandemic. This year her company is on track to facilitate 775 sales across Canada, mostly of businesses worth between $2-million and $20-million and having four employees or more.

“When you buy a business, the previous owner made all the expensive mistakes to build it, it has a customer base that’s already there, it’s easier to get capital because you have historical financials, and you get key staff at a time when there’s such large labour shortages,” she said. “I wouldn’t wish startups on anyone after running my own for 12 years.”

Other long-standing challenges to entrepreneurs have only gotten more entrenched over the last three years, like corporate concentration and the lack of competitiveness that comes with an economy dominated by oligopolies in several key industries.

Bonar McCallum, who co-owns a physiotherapy and fitness clinic called Move to Move with his wife in Calgary, experienced that first hand. Last year one of his largest competitors, the national physio chain Lifemark, was snapped up by Loblaw Cos. Ltd. for $845-million.

While his independent business had to take on debt during the pandemic, such as a $60,000 pandemic loan from the government that he hasn’t been able to repay yet, Loblaw backstopped his rival with its grocery and pharmacy divisions, which flourished during the lockdowns.

“If we’re weaker because of what we’ve come through, and these other companies are stronger because of where they’ve come from, this is a trend I don’t think is healthy,” Mr. McCallum said.

This concentration of Canada’s economy – fewer companies holding greater market shares – makes it tough for small players to compete against their bigger rivals while also reducing the number of potential suppliers.

“Competition is about experiments, about trying new things, new products, new ways of operating,” said Keldon Bester, co-founder of the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project. “When you consolidate, you – at a minimum – reduce the incentive for this kind of innovation and experimentation, but also the places where it can occur.”

For all these challenges, however, Canada’s entrepreneurs are an optimistic bunch. You have to be to take the financial and emotional plunge necessary to transform a business idea into reality. And many see the current weakness in entrepreneurship as a blip and not the start of an entrenched trend.

That’s certainly the outlook Mr. Sandhu, the founder of fintech upstart Otter, is taking as he builds his new business catering to other self-starters.

Though he didn’t plan it this way, he said the timing of Otter’s launch is fortuitous given the likely effect a slowdown will have on peoples’ startup plans. “As the economic cycle turns, we’re going to see nascent businesses fire up,” he said. “For people who have always wanted to pursue entrepreneurship, it could be the kick in the pants they need to try the thing they’ve been dreaming about.”

JASON KIRBY

CHRIS HANNAY, INDEPENDENT BUSINESS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, July 1, 2023