One new hire refused to unpack his boxes for months, unwilling to settle in when he could be fired any time. Another describes working through the night in a fruitless bid to allay her fear of the axe, and says pushing the elevator button at work every morning is like a “trigger” for her anxiety.

If you know anything about the workplace culture at Netflix Inc., it might be this undercurrent of dread. Behind it is a principle that “adequate performance gets a generous severance package.” Even good, hard workers are not safe if they are not exceptional; managers are encouraged to use a “keeper test” to fire anyone that they would not fight hard to keep if that person said they were leaving.

“It’s not untrue,” chief executive Reed Hastings said in an interview with The Globe and Mail, of the reports of fear that these policies engender in some employees. “But it’s not the full truth, either.”

Mr. Hastings’s new book aims to paint a broader picture of the company’s management philosophy. Written with Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD business school, No Rules Rules outlines a way of working that Mr. Hastings believes is intrinsic to Netflix’s success thus far.

If you are like millions stuck at home this year, and pressing play – whether to distract yourself from the global pandemic, or perhaps in the hope that Peppa Pig will provide a blessed respite for parents to get an ounce of work done – you already know just how popular Netflix is.

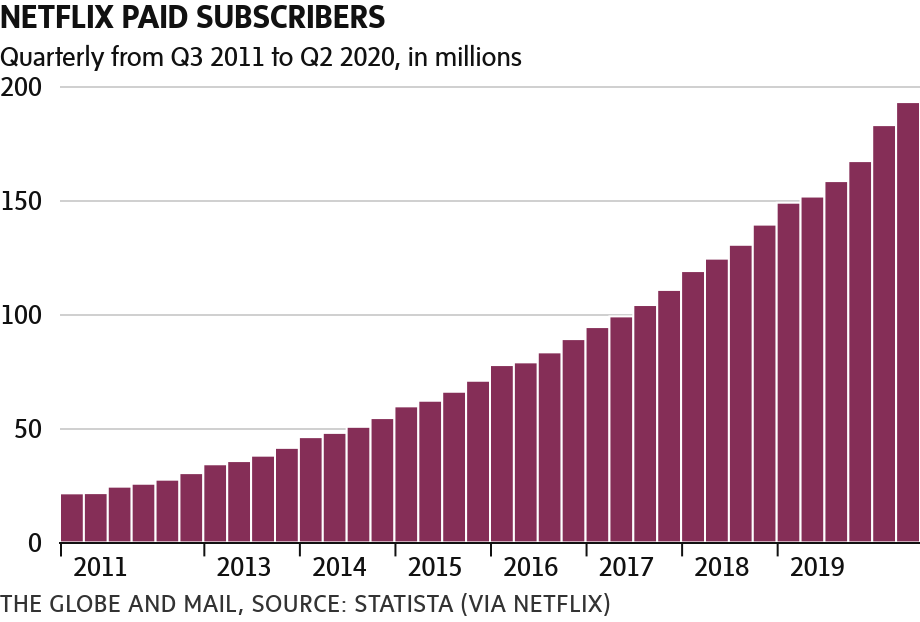

The company has enjoyed staggering growth over the past decade, creating streaming habits and transforming the home-entertainment landscape in the process. The company now counts nearly 193 million global subscribers, adding 26 million just in the first half of this year. Netflix had US$1.87-billion in net income in 2019, more than triple what it earned just two years earlier. It spends billions of dollars every year on content that shapes pop culture.

The foundation of all of this, Mr. Hastings says, is a way of working that prioritizes hiring and keeping the best talent; allows those people freedom to make decisions without having to ask their bosses for permission; encourages transparency to ensure people have the information they need to make those decisions; and requires constant feedback so that people are accountable for their choices, problems are addressed and people learn from failures.

“For 300 years, the factory has been the dominant [management] paradigm. It’s very top-down,” Mr. Hastings said, speaking on a video call from his apartment in Hollywood. While strict oversight and clear processes are still important for workplaces that depend on consistency, such as a factory – or where safety is paramount, such as a hospital – they do not help companies adapt in the information age, he said. “In a creative organization, you really want to stimulate people and inspire them, rather than supervise them.”

What it takes to make this work will sound unfamiliar to people accustomed to a typical corporate environment. For example, Netflix encourages employees to take calls from recruiters, and even go on interviews: That way, the company knows what those people are worth on the job market, and can pay them top dollar to keep them. The flip side of this is that managers are also expected to let go of those who are not top performers, with the assumption that mediocrity is infectious and can drag teams down.

People who work at Netflix also need to develop a tolerance for receiving constant feedback from colleagues, and giving it to others – as long as the aim is to help someone rather than an airing of grievances. And as long as it comes with suggestions for action that a person can take to fix the problem. This can be informal, but can also include larger sessions where people give each other feedback in front of a group.

Mr. Hastings acknowledges that this is deeply uncomfortable.

“Human society has developed where we’re polite and indirect, partly to avoid having wars,” he said. “And so those influences are very strong in us, of not saying what we’re really thinking. … But we’re not trying to do pain minimization; we’re trying to do growth maximization.”

Co-author Prof. Meyer, who studies differences in national cultures, did not expect this model to work, especially in parts of the world that prize group harmony. Even where blunt and direct communication is accepted, she was concerned that such sessions could turn into a “free-for-all.” Prof. Meyer interviewed more than 200 employees to get a sense of how things are in the middle of the company, not just how they look from the CEO’s chair. Now, she thinks this should happen everywhere.

“No matter what your level of comfort is with day-to-day candour, when you get that kind of feedback … performance leaps up,” she said.

Another key feature of the culture Mr. Hastings describes is a removal of controls. That means people are in charge not just of how much vacation they take, but also for major decisions on behalf of the company.

“What leads to the success is this enormous freedom that employees are given,” Prof. Meyer said. “… Employees in the information age need freedom to innovate fast and be flexible as things change around them.”

Bosses share information so that people make those decisions with the proper context – whether big bets such as spending an unprecedented US$4.6-million for the documentary Icarus, or smaller considerations such as knowing when to take vacation or which travel expenses are in the company’s interest.

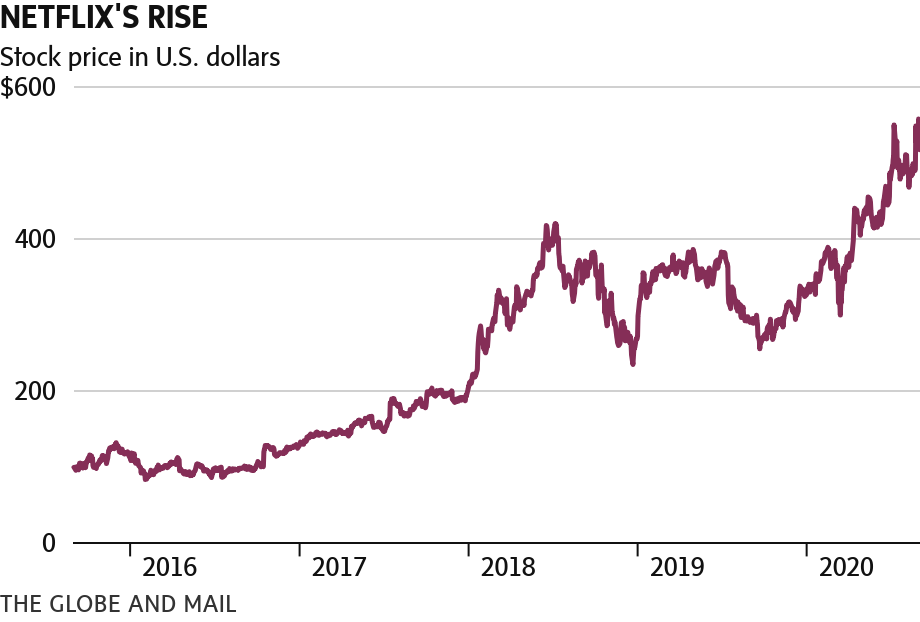

“The traditional version of a good firm is highly efficient, no waste, very orderly. And that doesn’t really stimulate creativity,” Mr. Hastings said. This might sound easy to say for a tech darling at the top of its game. But the company began to develop these practices early on, even as it fought to compete with the behemoth that was Blockbuster, when the stock was volatile, and when the company was not making money.

“We had all these cultures during the tough times, and they were essential,” Mr. Hastings said.

Now, Netflix is in a very different position: It has led the growth of streaming, and while it has a head start, the world’s biggest entertainment companies are fighting hard for a piece of that market. Streaming services – including Disney+, Amazon Prime and Apple TV+ – have proliferated.

Competing in this crowded market means constantly releasing new movies and shows to keep people watching. Netflix spent more than US$15-billion on content last year, a number that is continuing to grow as it battles to win subscribers and keep people signed on.

But this is a high-wire act. Netflix has recorded negative free cash flow for years – it only veered into positive territory in the first half of this year, but that was with abnormal subscriber growth and abnormally low costs as productions ground to a halt, both a side-effect of COVID-19. The cash burn isn’t a concern, Mr. Hastings said, because it’s part of the company’s rapid growth.

“As we get bigger, then we become sustainably, and hopefully substantially, free-cash-flow positive,” he said. How long this takes will depend on future growth.

RBC Capital Markets analyst Mark Mahaney says he believes there is still a lot of room to grow: He recently estimated that, even without being able to do business in China, Netflix could reach 500 million subscribers some time within the next decade, and that it could be free-cash-flow positive within a couple of years. Mr. Mahaney has conducted consumer surveys in various markets and found that as people cut the TV cord, they are willing to pay for a number of different streaming services.

“There’s so much focus on Disney versus Apple versus Netflix. … We’re going through the growth of the streaming bundle,” Mr. Mahaney said.

With that comes risk, however. It’s a headache to sit on hold with the cable company and cancel your TV service; it’s easy to turn streaming subscriptions on and off. With choice proliferating, it’s becoming more and more expensive to have a streaming bundle. It’s possible that as competition intensifies, people may sign up when they want to binge a new offering, and duck out again to save money.

So far, Mr. Hastings said, that has not been a problem: He says he believes the company is making enough new content to keep people happy. But he knows how quickly things can change – he went from offering to sell Netflix to Blockbuster in 2000 for US$50-million (an offer Blockbuster rejected) to hastening its giant competitor’s demise.

“It’s our job just to keep producing the most interesting, most provocative, most compelling entertainment we can,” he said. “… We should always stay curious about what the next thing may be.”

SUSAN KRASHINSKY ROBERTSON

RETAILING REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, September 5, 2020