Higher TFSA contribution limits could cost us all.

Launched in 2009, tax-free savings accounts may be the most important development in Canadian personal finance since the introduction of the registered retirement savings plan back in the 1950s. TFSAs are Swiss army knives – a financial knife, corkscrew, screwdriver and more. But doubling the annual contribution limit of $5,500 is a bad idea.

Message to the federal government: Please don’t, because we can’t afford it.

At issue is the tax revenue the federal government goes without when someone puts money in a TFSA. While contributions are made with after-tax dollars, all investment or savings gains in the account are, like the name says, tax-free.

TFSAs are widely popular, but they’re new enough still that they cost the government only $410-million in tax revenue in 2013. Future contributions to TFSAs and continuing tax-free gains within them will push this number higher in future years, but we can live with that because of the benefits of having people use these savings vehicles. Doubling the amount of money people can put in TFSAs to $11,000 is pushing it, though.

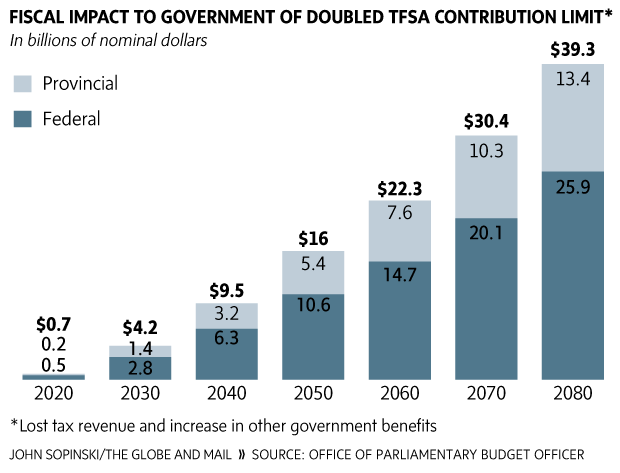

A report from the Parliamentary Budget Officer this week says the federal government would lose $14.7-billion a year in revenue by 2060 and the provinces would lose $7.6-billion a year. That’s a tremendous amount of money to forgo in a country with a population aging as quickly as ours.

The latest population estimates from Statistics Canada suggest that seniors will account for 25.5 per cent of the population by 2061, up from 14.4 per cent in 2011. You can imagine what this trend will mean for government spending on health care and income programs such as Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement.

In fact, Ottawa was so concerned about the sustainability of OAS – it’s funded from general government revenue – that it announced that it would gradually increase the age of eligibility to 67 from 65 starting in 2023. Ottawa saved a whack of money doing that. Now, it’s looking at depleting the savings it realized with a higher TFSA contribution limit.

An aging population will weigh on our economic productivity, so we can’t depend on future growth to sustain government spending. This suggests taxpayers will have to pick up the slack. Higher taxes are one possibility, although they’d be a tough sell for any government facing an electorate with a heavy weighting of seniors.

Reduced health-care coverage is another lever for governments with a revenue shortfall. More services and procedures could be delisted from provincial health-care plans, which means more out-of-pocket expenses for the prime consumers of medical services. Seniors of the future, that’s you.

Finally, higher TFSA limits would put a strain on OAS and GIS and possibly lead to benefit cuts or more severe clawbacks. One of the benefits of TFSAs is that money you withdraw from them isn’t considered taxable income and thus can’t trigger clawbacks of OAS or GIS benefits for retirees. If more people use TFSAs to generate retirement income, then there will be fewer clawbacks and thus more GIS and OAS money being paid out.

Seniors hate those clawbacks, but let’s remember why they’re there. It’s to ensure that full benefits go to individuals who need them, and to taper these benefits down for more affluent seniors. To conserve OAS and GIS, clawbacks might actually have to become more aggressive if we raise the TFSA limit.

A report this week by Prof. Rhys Kesselman of Simon Fraser University makes a case that doubling the TFSA contribution limit benefits mainly the wealthy, and it’s persuasive. The report says that in 2012, the most recent year for which there are numbers, just 23.5 per cent of TFSA holders made the maximum contribution, down from 30.2 per cent in 2011 and 39.6 per cent in 2010.

But TFSAs are so versatile that higher limits would benefit more than just rich people. Young people saving for a house would have more room to build their down payments without losing money to tax. Seniors would have more space to shelter money they’re required to withdraw every year from their registered retirement income funds, but choose not to spend.

Higher TFSA limits are a fine idea, but we have to weigh the short-term tax savings for households against the long-term strain on government finances. Decades from now, we may look back on an increased TFSA limit and say it really cost us all.

ROB CARRICK

The Globe and Mail

Published Wednesday, Feb. 25 2015, 7:19 PM EST

Last updated Thursday, Feb. 26 2015, 8:19 AM EST