For most people living in Western Canada, smoky haze and reduced air quality are par for the course during wildfire season. But when visibility was reduced, the air smelled of smoke and the sun burned red in the middle of the day, those living in southeastern Canada were reminded that they are not immune to the impact of out-of-control forest fires raging hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away.

“As long as there are forest fires, we have a source of smoke,” said Toronto-based Environment Canada meteorologist Gerald Cheng. “And then it’s about watching where the wind will take it.”

This week, meteorological forces conspired to push smoke from fires burning in Northwestern Ontario and Northern Manitoba on top of major cities such as Montreal, Fredericton, Winnipeg and Toronto. On Monday evening, downtown Toronto logged the highest air pollution figure recorded since the air quality station started reporting in 2003, Mr. Cheng said. “It’s a big deal,” he said. “It doesn’t happen often in this part of Canada. … It’s harder for wind to carry smoke all the way to Toronto and Montreal and maintain a level of concentration that’s of concern.”

The level of concentration of what’s known as PM2.5 – the fine, airborne particulate matter present in wildfire smoke – has, indeed, been of concern in broad swaths of the country this week. With hundreds of out-of-control wildfires burning across the country, Environment Canada air quality warnings were in effect this week from British Columbia and the Northwest Territories all the way to Nova Scotia. While a cold front from Hudson Bay brought cleaner air and rain into Southern Ontario and Southern Quebec on Tuesday evening, parts of the Maritimes won’t see relief until Thursday evening, Mr. Cheng said. For those in Southern Manitoba, the smoke will likely persist until Thursday afternoon, when a low-pressure system pushes the plume back north. “And then we’ll see who’s next, unfortunately,” he said.

Several large Canadian cities, including Edmonton, Regina, Winnipeg and Montreal received high-risk air quality ratings this week. When air quality is so poor to merit such a rating, Canadians with underlying respiratory or heart problems are advised to reduce their time outdoors.

As the haze continues to lift from parts of the country that don’t typically see, smell or breathe wildfire smoke, The Globe and Mail lays out what Canadians need to know about where the smoke is coming from, how it can affect human health and what people can do to stay safe.

WHICH PARTS OF CANADA ARE UNDER SMOKE?

The better question might be: Which parts of Canada aren’t under smoke? As of midday Wednesday, at least some portion of B.C., Northwest Territories, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia was subject to an Environment Canada air quality warning owing to wildfire smoke. While cities in Western Canada such as Vancouver, Kamloops and Yellowknife experience smoke exposure every fire season because of their proximity to the flames, it’s uncommon for major Eastern Canadian cities such as Toronto, Montreal, Fredericton and Halifax to fall under the sort of haze that covered those locations this week. Although the concentration of smoke may not be enough to affect visibility in some areas, that doesn’t mean the air quality hasn’t been detrimentally affected.

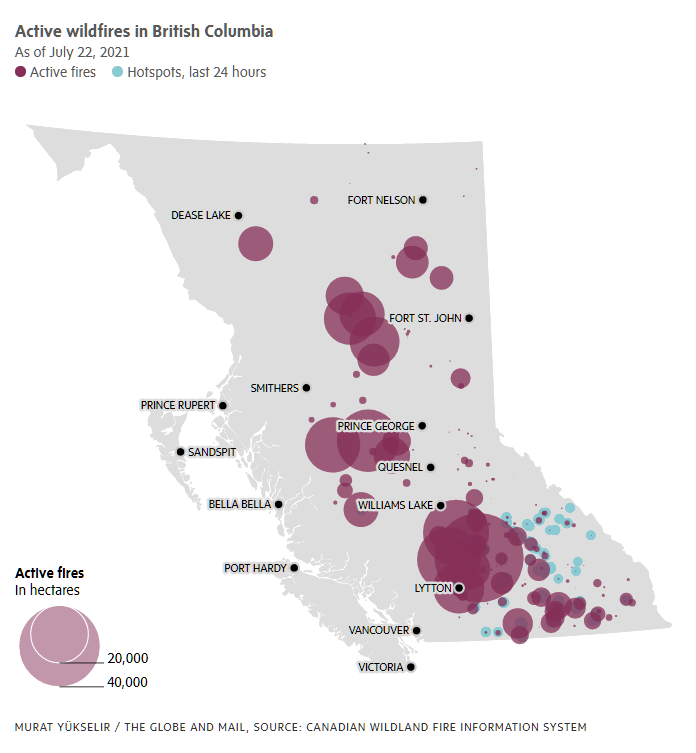

WHERE ARE WILDFIRES BURNING?

Hundreds of out-of-control wildfires are burning in Canada. They are concentrated in B.C., Yukon, Northwest Territories, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario, with at least two large out-of-control fires burning in Northern Quebec, according to Natural Resources Canada’s Canadian Wildland Fire Information System information for Wednesday. The majority of the forest fires in Ontario are located in the northwestern portion of the province. “It’s quite significant when you think about how the smoke has travelled,” Mr. Cheng said, referring to the plume that moved from Northwestern Ontario and Northern Manitoba into Southern Ontario, Southern Quebec, the Maritimes and even into the Northeastern United States. “It has no boundaries.”

WHERE DID THE SMOKE OVER SOUTHERN ONTARIO, SOUTHERN QUEBEC AND THE MARITIMES COME FROM?

Typically, the smoke from wildfires burning in Northern Manitoba, Northwestern Ontario and Northern Quebec doesn’t make its way down to communities in Southern Ontario, Southern Quebec or the Maritimes – or if it does, the smoke has been diluted so much that it doesn’t affect visibility or air quality in a noticeable way. On the weekend, though, Mr. Cheng saw trends in the forecast that predicted smoke would move eastward from Manitoba fires, and that a high-pressure system in Northern Ontario would push wildfire smoke down toward populated areas in Southern Ontario and Southern Quebec. He knew the air quality would deteriorate where he lives, in Toronto; it was just a matter of how badly – and when. That same band of smoke then made its way further east, to New Brunswick, where visibility has been reduced, and Nova Scotia. Manitoba has also been affected by smoke from Northwestern Ontario, with the haze and air pollution reaching south to Winnipeg.

WHAT’S IN THE WILDFIRE SMOKE?

Not every breath of smoke is created equal, because not all wildfire smoke is created equal. In addition to gases such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds, smoke is also full of particulate matter – solid particles and liquid droplets of varying sizes. When it comes to smoke exposure, air-quality indexes and studies tend to look at what’s known as PM2.5, which is a composition of fine particles with diameters less than 2.5 microns. That’s about 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. The composition of the PM2.5 depends entirely on what, exactly, is in the line of fire. Grasses, trees, houses and cars, for instance, all release different substances into the air when burned.

HOW DOES PARTICULATE MATTER FROM WILDFIRE SMOKE AFFECT AIR QUALITY?

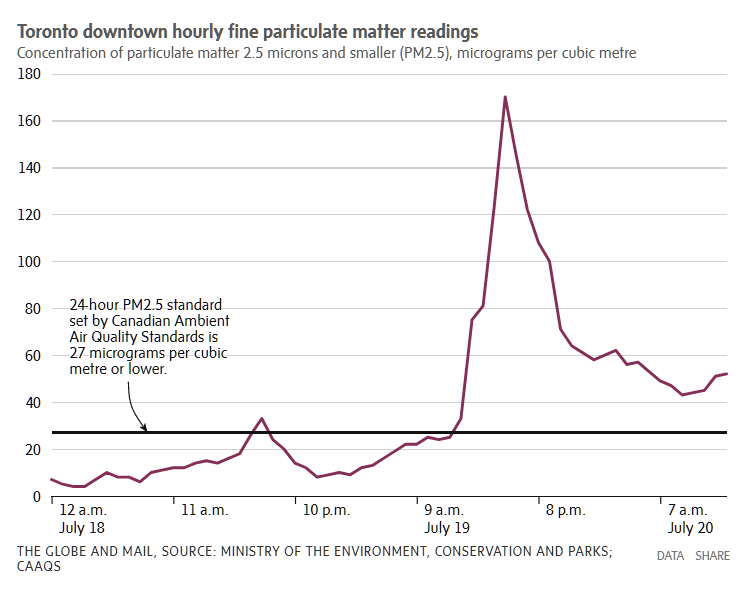

About a decade ago, the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment developed the Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards for PM2.5; the standard is currently met when average annual levels of PM2.5 are 8.8 micrograms for every cubic metre or less, and when the 24-hour average is 27 micrograms for every cubic metre or less.

In B.C., where air quality is generally very good, the 24-hour average of PM2.5 detected in the air would typically be lower than 10 micrograms for every cubic metre, said Sarah Henderson, scientific director in environmental health services at the BC Centre for Disease Control. On the smokiest days in the province, the PM2.5 value could hit 300 or more. With concentrations that high, visibility is greatly reduced and, as Dr. Henderson put it in a recent interview, “You can smell the smoke and taste it.” But it’s at levels of just 30 or so that the population starts to respond adversely to the smoke. “When it looks really bad, people think it is really bad,” she said. “But it becomes unhealthy long before it looks terrible.”

HOW BAD DID THE AIR QUALITY GET IN MAJOR EASTERN CANADA CITIES SUCH AS TORONTO, MONTREAL AND FREDERICTON?

By 2 p.m. on Monday, Toronto was ranked second in the world among major cities for air pollution, behind Jakarta, according to IQAir, a Swiss technology company that measures air-quality levels based on the concentration of PM2.5. By 5 p.m., the air-quality station in downtown Toronto logged a PM2.5 value of 170 micrograms for every cubic metre – the highest concentration recorded by the station since it started reporting in 2003. “It’s a really, really rare event,” Mr. Cheng said. By Tuesday night, the downtown Toronto station recorded a PM2.5 level of just 7.

In Quebec, the Saint-Dominique air-quality station on the Island of Montreal recorded a PM2.5 level of 66 as of around midnight Monday; that figure dropped to 6 by noon Wednesday. Further east, in New Brunswick, Fredericton reached a PM2.5 level of 39 at 2 p.m. on Tuesday; by noon Wednesday, that figure was already down to 9.

HOW DOES WILDFIRE SMOKE AFFECT OUR HEALTH?

PM2.5 can reach deep into the lungs, prompting the body to mount an immunological response just as it would if it detected the presence of an unwanted bacteria or virus. “The immunological response ends up causing inflammation, and that inflammation is systemic,” said Dr. Henderson, who has been studying wildfire smoke for two decades and has published upward of 40 papers on the topic. In other words, particulate pollution from smoke can affect every organ system in the body.

So while people with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the canaries in the coal mine of wildfire smoke, the inflammation can also increase the likelihood of a cardiovascular event such as a heart attack or a stroke. Emerging research also suggests the body’s response to smoke exposure can make it harder for people with diabetes to balance their insulin levels, and may affect brain function for those whose cognitive abilities are already compromised.

WHEN ARE THINGS IN SOUTHEASTERN CANADA GOING TO IMPROVE?

Already, the smoke has moved off Toronto and Montreal, owing to a cold front and rainfall that passed through Southern Ontario and Southern Quebec on Tuesday evening. “The air behind the cold front is a much cleaner air mass – it’s not coming from where the fires are,” Mr. Cheng said. For parts of the Maritimes, though, residents will have to wait until Thursday evening to see the smoke dissipate, when that same cold front brings cleaner air into the area.

As for Southern Manitoba, the PM2.5 reading in Winnipeg on Wednesday morning was 76 micrograms for every cubic metre – nearly three times the 24-hour Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standard. Mr. Cheng said the smoke will soon be pushed north by a low-pressure system moving into the area.

WHAT CAN YOU DO TO STAY SAFE IF YOU’RE IN AN AREA WITH POOR AIR QUALITY?

“We can avoid exposure and minimize activities outside,” Mr. Cheng said. “If you have air filtration, use it.” He also said the face masks Canadians have become used to during the pandemic can also help, as they can filter out some of the airborne particles.

Homeowners with air conditioning can set the system to recirculate. They can also install a high-efficiency particulate air, or HEPA, filtration system and ensure windows remain tightly closed. Mostly, at the individual level, it’s about paying attention to the air quality and behaving accordingly, Dr. Henderson said in the recent interview.

While she’s not suggesting that, say, a new mom and dad need to move from a smoke-prone area of the country because they’ve just had a baby, she is suggesting the parents consider getting an air-filtration system for the home or a portable air cleaner for the infant’s room. “It’s the fine line,” she said, “between panic and caution.”

At the public-health level, efforts may involve earlier warnings of poor air quality to get people indoors sooner, and more clean-air shelters to serve those experiencing homelessness. Building codes could also be amended to require more vigorous ventilation standards.

WHY DOES WILDFIRE SMOKE MAKE THE SUN APPEAR SO RED?

As the smoke lingered over Southern Ontario and Southern Quebec, residents took to social media to post photos of a bright red sun hanging in the sky. This, Lucie Robillard said, is the “science of light.” Ms. Robillard, science communicator for the planetarium at Science North in Sudbury, Ont., said while the effect is quite beautiful, it’s a result of those polluting air particles present in the wildfire smoke. “The particles scatter a lot of the blue light, leaving a lot of the longer wavelengths, like the reds and oranges, to get through and reach our eyes,” she said. This happens naturally at sunrise and sunset, she said, explaining that when the sun is closer to the horizon, the sunlight has to go through more atmosphere before reaching our eyes. The light that reaches our eyes, then, is most concentrated with red and orange frequencies.

WHAT’S THE FUTURE OF WILDFIRE SMOKE IN CANADA?

Wildfire experts, climatologists and doctors warn that as the climate warms, Canada is headed for record-smashing high temperatures, longer and increasingly intense wildfire seasons and, in turn, prolonged periods of smoke exposure. This month, international researchers released analysis that suggests climate change made the June heat wave that started in the Pacific Northwest 150 times more likely than it otherwise would have been. The future of wildfire in Canada is, in a word, more. And so, too, then, is the future of wildfire smoke in this country. As more wildfires burn at greater frequency and intensity, the risk of smoke exposure for Canadians living near to – and even far from – the blazes will increase as well. As this week’s haze and poor air quality in major southeastern cities has shown, Canadians don’t need to reside near a wildfire to see, smell or feel the effects of it.

KATHRYN BLAZE BAUM

ENVIRONMENT REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, July 20, 2021