If flirty dresses and bright colours were signs of a strong economy, you might think consumers are on to the next spending spree.

After months of a lockdown-related boom in loungewear, more formal attire is bouncing back, and shoppers are gravitating to brighter hues.

“You can sense that there’s effervescence in the marketplace right now, with people returning to work, getting back to social activities – weddings, outings, cocktail parties,” said Bernard Leblanc, the chief executive officer of Montreal-based retailer Simons.

But behind the summer party atmosphere lurks mounting anxiety in the retail sector. In addition to the problems that have dragged on for months – rising costs for raw materials and for transporting goods to store shelves – new factors are further complicating many companies’ operations.

For one, consumers are becoming more pessimistic as inflation drags down confidence in the economy. Buying patterns are shifting as people recoil from rising prices but also look to spend more on rebounding service sectors. The war in Ukraine is further driving up high commodity prices. And some retailers have swung from empty shelves to a glut of inventory, which they may struggle to offload at reasonable margins.

To get inflation under control, central bankers are now raising interest rates at the quickest pace in decades, trying to curb demand in the economy. For many households, it will be a rude awakening, as higher borrowing costs eat into family budgets.

Last month’s rout in retail stocks followed discouraging earnings reports from big names in the U.S., such as Walmart and Target, which pointed to some of these trends. While the effects of these shifts will be felt differently across retail categories and price points, there are choppy waters ahead for many. In May, an index of consumer confidence published by the Conference Board of Canada saw its biggest drop since the outset of the pandemic.

“If we don’t see weak spending right now, it’s really a matter of time,” said Sohaib Shahid, director of economic innovation at the Ottawa-based think tank.

THE BIG SHIFT

Retailers knew things would start to change this year. As the economy opens up, and people increasingly go out to have fun, they are naturally reallocating some of their spending from goods – yoga pants, puzzles, new couches – to services such as restaurants and hotels.

Still, some retail operators have been caught off guard by just how much consumer behaviour has changed.

“While we anticipated a post-stimulus slowdown in these categories and we expect the consumer to continue refocusing their spending away from goods and into services, we didn’t anticipate the magnitude of that shift,” Target Corp. CEO Brian Cornell told analysts on a recent call, after the Minneapolis-based company reported a significant deceleration in earnings growth. In its first quarter, Target saw comparable sales grow 3.3 per cent, compared with a 23-per-cent gain in the same period last year.

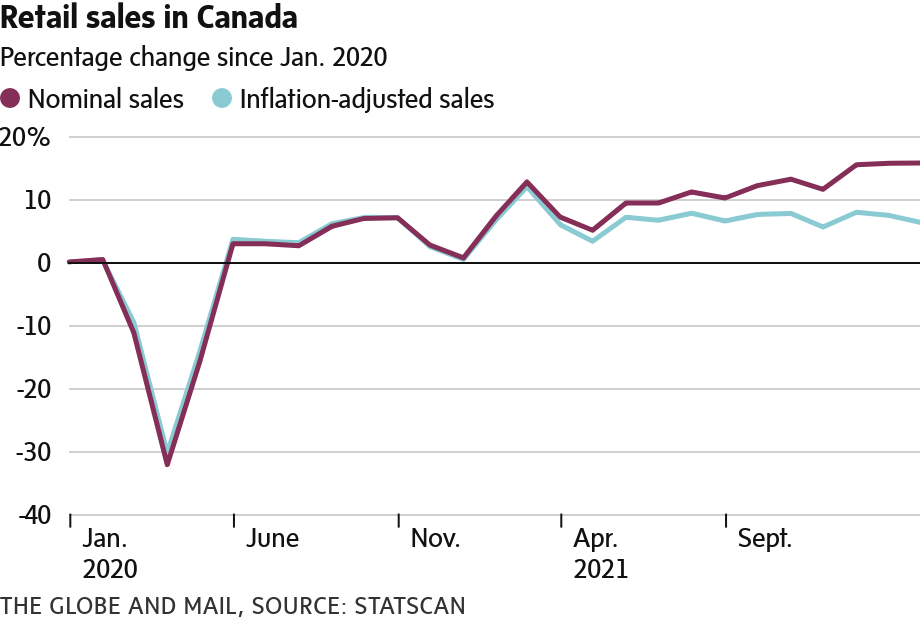

In Canada, retailers sold about $60-billion of goods in March, about 15 per cent more than just before the pandemic, according to the latest Statistics Canada figures. But that doesn’t mean people are buying more stuff: After adjusting for inflation, retail sales have essentially flattened since early 2021, with consumers simply paying a lot more for the same volume of goods.

There are indications that, like U.S. consumers, Canadians have begun to alter their spending patterns. Outdoor retailer MEC is currently stocking up on private-label products such as rain jackets and tents, expecting higher demand as shoppers shy away from pricier name brands. And the country’s largest grocers have reported that people are buying more of their private brands and are returning to discount grocery stores. The reverse happened at the height of the pandemic, when people flocked to full-service banners in search of one-stop shopping.

Not all retailers are seeing this shift. In recent meetings with analysts, Canadian Tire Corp. executives indicated that demand for big-ticket items is “solid and consistent with pre-pandemic levels,” Royal Bank of Canada analyst Irene Nattel wrote in a research note last week. Canadian Tire has also not seen shoppers “trading down” to cheaper items yet, she added.

And Yeti coolers are still outselling lower-priced options, said MEC chief operating officer Jay Taylor. “They don’t want to buy the $100 item and have to replace it two years from now.”

For retailers, it helps that many households built up savings over the past two years thanks to government stimulus programs and lockdowns that limited their spending options. Moreover, jobs are plentiful, and wages are rising in both the U.S. and Canada, bolstering household budgets.

The cache of savings is larger among high-income households, who are more likely to spend big on travel and restaurants. And there’s certainly room for them to ramp up spending: After accounting for inflation, spending on services in Canada has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Retailers on either end of the spectrum – those selling higher-end goods to well-off customers or discounters catering to deal hunters during an inflationary period – are likely to feel the least impact, said Marty Weintraub, who leads Deloitte’s national retail consulting practice in Canada.

“If you’re serving the mushy middle, be careful, because that’s where the disruption is going to be the biggest,” he said. “If we go to the more discretionary parts of retail – apparel, department stores – that’s where there’s going to be a little bit of a bigger hit.”

Despite some encouraging economic trends, many people feel less well off. In a survey of more than 3,000 Canadians in March, Boston Consulting Group found that almost 40 per cent of respondents with incomes below $50,000 and 21 per cent with incomes above that level felt less financially secure than they did before the pandemic.

The persistence of lofty inflation – particularly rising prices for food and gasoline – is weighing on sentiment, which could eventually hit consumption.

“A lot of that is facing a trade down: ‘I’m going to spend more efficiently, I’m going to spend less, I’m going to go to a different type of retailer like a discounter,’” said Kathleen Polsinello, managing director and partner at Boston Consulting Group. “Those trends are starting.”

‘HIGHER THAN WE WANT’

The ongoing global supply-chain disruption, mixed with these changes in buying habits, is making it more difficult for retailers to forecast the levels of inventory they need or can expect from suppliers at any given time. Walmart, Kohl’s, Target, Abercrombie & Fitch and Foot Locker all said recently that inventory levels have increased significantly over last year. Now, after scrambling to meet demand, some are stuck holding product that not enough people want to buy. At Target, that includes electronics, clothing and kitchen appliances – some of them bulky items that take up valuable warehouse space.

“We like the fact that our inventory is up because so much of it is needed to be in stock,” Walmart CEO Doug McMillon told analysts on a recent earnings call. But “a 32-per-cent increase is higher than we want.”

In 2020 and 2021, cancellation rates on inbound shipments from suppliers spiked – from the usual 8 per cent to 10 per cent to 25 per cent to 30 per cent, MEC’s Mr. Taylor said.

“So virtually every retailer I know has too much product on order, or coming in, for their sales plan. Everyone is starting to cancel product [orders]. The bigger they are, the harder it is to react quickly enough,” he said. “If consumers put their hands in their pockets, everyone’s going to be a bit dinged.”

In its case, MEC is receiving some of that inventory anyway – boats, for instance, to make up for shortages last year – but is cancelling other orders such as apparel items it will not need.

Some retailers can hold on to goods until the following season if they do not sell, but lower-priced players or fast-fashion stores that need to clear inventory to make way for the next season could be forced to mark down items to move them off the shelves. That’s exactly what Target announced it would do this week, saying it was cancelling some product orders and would slash prices on inventory the company over-ordered to clear it out before the holiday shopping season. If more retailers determine that aggressive promotions are needed, that would be good news for consumers struggling with inflation – but bad news for companies that have seen costs go way up.

GOING UP

For months, it has been more expensive to get products to shelves. Prices for shipping by sea have gone up, and container shortages have led some retailers, such as Vancouver-based Aritzia Inc. and Lululemon Athletica Inc., to rely on even pricier air freight. Ocean shipping times are not yet improving, Lululemon CEO Calvin McDonald said on a call with analysts last Thursday.

“Certainly there are inflationary pressures. We are seeing that in increased freight costs and some raw materials,” Aritzia CEO Jennifer Wong said in a recent interview with The Globe and Mail. Aritzia has resisted raising prices on products it has carried for some time but is being strategic about how it prices new items to ensure margins are healthy, she added. “We haven’t seen any change in momentum for demand at this time, which is really encouraging.”

Still, cost pressures are continuing – and the spike in fuel prices since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made a bad situation worse. Even operators known for managing inflationary cycles, such as Walmart, have struggled.

In the grocery aisle, retailers are dealing with an unprecedented number of requests from suppliers for wholesale price increases, Canadian executives have reported. In some instances this has led to nasty spats – such as the one between Loblaw Cos. Ltd. and Pepsico-owned snack giant Frito-Lay, which stopped shipping products to Loblaws stores when negotiations stalled over price hikes for potato chips. (The dispute has since been resolved.)

Some businesses are “quite willing to pass through higher costs to customers, because that tolerance is there – people are paying those higher prices,” said Sal Guatieri, a senior economist at Bank of Montreal.

That trend is visible even at the lowest end of the market. In March, Montreal-based discounter Dollarama Inc. announced that after six years of holding to a maximum price point of $4, it would soon begin selling products at $5. But on a conference call with analysts, CEO Neil Rossy said the company does not expect “the kind of margin expansion we’ve seen historically following the introduction of new price points,” simply because costs are higher.

In the apparel and footwear space, there has been relatively little inflation in recent years, said Mr. Leblanc of Simons, which gives retailers “a little bit of room” for price increases.

“But I think everybody is staying timid, for the time being. There’s a limit to what the customer can bear,” he said. “They’ve been accepting so far, but we have to be cautious.”

SUSAN KRASHINSKY ROBERTSON, RETAILING REPORTER

MATT LUNDY, ECONOMICS REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, June 10, 2022