Photos of the days of gangsters, casinos and Frank Sinatra line the hallways of the century-old Hotel Sevilla in Havana, the pictures a reminder of what Cuba was before Fidel Castro and his band of Sierra Maestra rebels changed the destiny of the island country forever. Like other wealthy Cubans, the Sevilla’s owner, a Uruguayan mobster by the name of Don Amleto Battisti y Lora, lost it all not long after the revolution of Jan. 1, 1959. Within a few years, tens of thousands of well-educated professionals had left, the majority embarking on what they thought would be a short-term stay in Miami.

Time flies. A virulent nostalgia has coloured relations between Cuba and the United States ever since, with the “Miami mafia” – the Communists’ favoured moniker for the exiles – funding and advocating for the overthrow of the regime, and the Cuban government warning that its death would return the country to the days when the Cuban-American Sugar Company employed thousands for poverty wages.

As that first wave of migrants has died and Fidel himself, 88, moves closer to that inevitable future, the revolution’s shadow has receded. In the words of U.S. President Barack Obama, the revolution and the years that followed are “events that took place before most of us were born.”

And so begins the beginning of the end, with an announcement that the United States will work to establish diplomatic ties and allow more travel and trade.

The United States will also reopen its embassy in Havana. The announcement is not an admission that the United States government has failed over the course of a 54-year embargo to destroy the regime. Instead, it’s an acceptance of the reality that the flow of money and people between the two states is unstoppable. Making those exchanges easier is the best chance the United States has of helping the benefits accrue equitably instead of only enriching the fortunate who have relatives abroad or worse, the connected inside.

Most importantly, the rapprochement between the two countries suggests the future: a day to come when the embargo could be lifted. That would deprive the regime of its perennial excuse for every failure, from internal political repression to the meagre rations that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. It’s why the country’s most prominent dissenter – blogger Yoani Sanchez – has long advocated for its end.

The fear in opening the window to the United States is that what will fly through it is the past.

Some have already glimpsed this future in the nightclubs and the Mercedes that drive along the Malecon even as the majority of the population is still holding together 1950s Cadillacs with electrical tape and elastics. The hope is that the opening is the beginning of an era that will see light bulbs return to the lamps on the Paseo del Prado and Americans take diving trips in the Bay of Pigs alongside Canadians. The hope is that those changes won’t take another five decades.

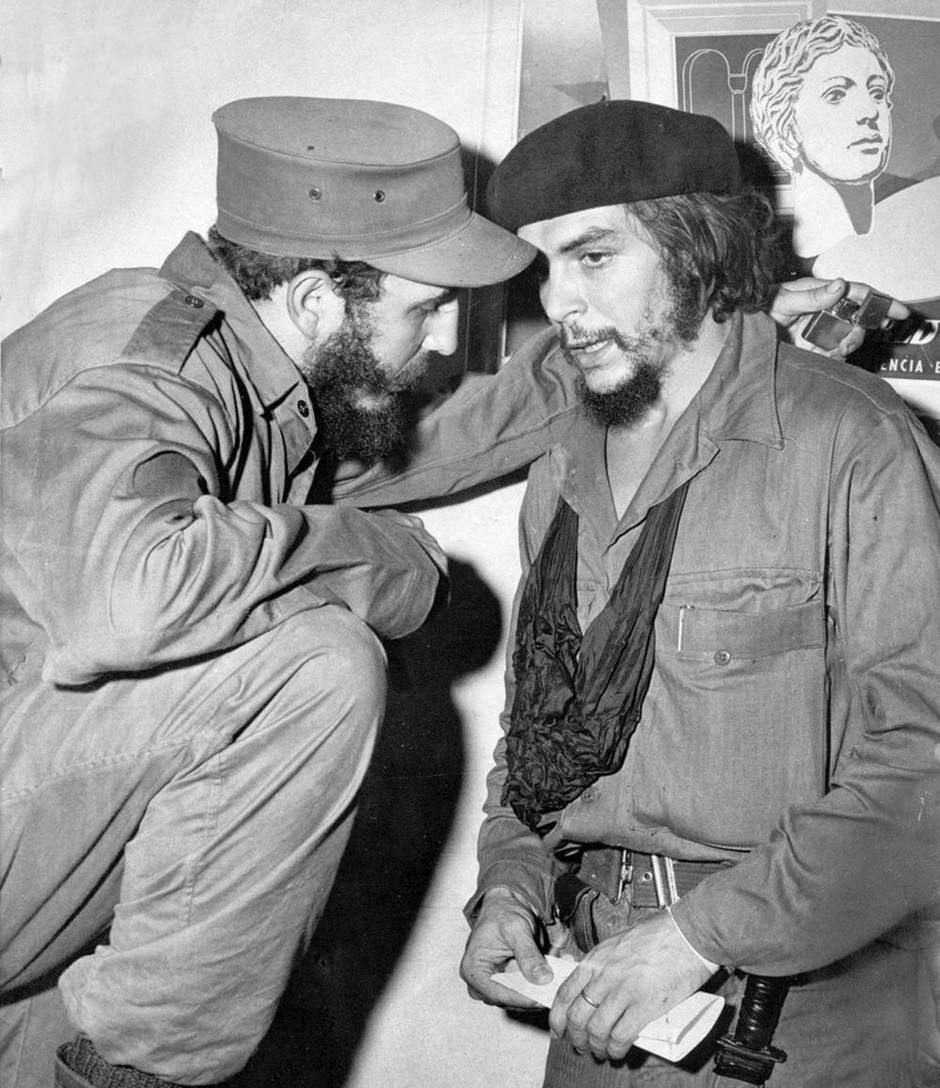

When they were friends

Rita Hayworth, Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Meyer Lansky. That was the gang that ruled Havana – and the American imagination about Cuba – in the 1950s. A “very lively atmosphere” in Irving Berlin’s words had pervaded the city for decades and American singers and showgirls would fly in overnight for shows at the Tropicana. “It never stopped,” said a society columnist of the time.

The swish had been built substantially on American economic and political domination. Periodic U.S. military interventions had protected the investments of the Cuban American Sugar Company and other U.S. companies from any hint of populist threat through the early part of the 20th century. Later, Mob money poured into luxury hotels, casinos and bars but much of the population did not benefit from the boom. It all came to an end on Jan. 1, 1959, when U.S.-supported President Fulgencio Batista fled to the Dominican Republican and Fidel Castro’s guerrilla forces formed a government.

‘Those who wait’

Fidel Castro’s arrival in power did not lead to an overnight exodus. In fact, it was hard to read the new administration and there were even disagreements about whether closing the casinos would turn off an important financial tap. Within a year, however, the government nationalized major industries and, to the upper class and much of the middle class, it became clear that the changes would not be in their favour.

Alejandro Portes, a sociologist and a Cuban-American, has baptized this first wave as “those who wait” who were followed not long after by “those who escaped.” The first group were waiting for a quick overthrow of the Castro government, the second departed after those hopes were dashed by the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. Politics were personal. When the government closed private schools and universities, well-off families sent 14,000 unaccompanied children out of the country.

A dialogue

The current opening to Cuba has a precedent in a dialogue in the 1970s between then U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Fidel Castro. The two leaders opened some diplomatic relations, allowed Cuban-Americans to visit relatives on the island and negotiated the release of political prisoners. Many Cuban- Americans were outraged. Extremists in this group had been implicated in terrorist attacks, including the bombing of a Cubana plane that killed all 73 on board.

These conversations culminated with the emigration of more than 125,000 exiles during what came to be known as the Mariel boatlift. They travelled in speedboats but also home-made rafts, taking advantage of U.S. laws that accepted refugee claims from any Cuban able to reach its shore. Twenty-seven refugees died trying to cross those 140 kilometres.

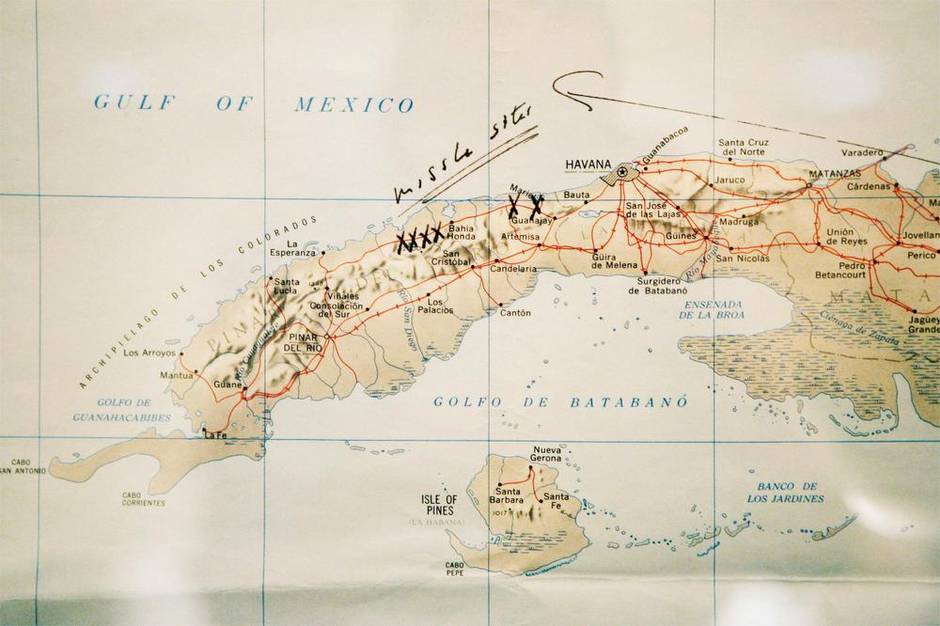

The Cold War

Without the Cold War, Cuba’s chances to withstand the American embargo, imposed less than a year after the revolution, would have been slim. Cuba’s turn to the Soviet Union for protection led to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, but for decades after it benefited from billions in trade, with the Russians buying sugar and exporting oil.

It was a dependence that would almost lead to Cuba’s collapse when the protection ended in the early 1990s and Cubans became accustomed to a new Russian import: lineups for everything.

Even as the Russians dominated, Canada was there too, never breaking off relations with the revolutionary government. Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau counted Fidel Castro among his friends. Canadians make up more than 40 per cent of Cuba’s tourists, drawn by the beaches, but also by a country still seemingly frozen in time.

Handing over the reins

According to some counts, there have been 638 assassination attempts on Fidel Castro’s life. That number suggests how some believed that killing the bearded leader would end the Communist Party’s reign. The past few years, since the elder Castro handed the reins over to his younger brother, now 83, show how wrong that calculation was. Raul is presiding over one of the most successful eras in Cuban history.

Indeed, it has been U.S. politicians who have made the larger adjustments. Until the 1980s, Cuban-Americans in Florida voted for the Democrats. Calculated efforts from Jeb Bush and George W. Bush stoked their support, promising no end to the embargo. The state has grown multiethnic, however, with a younger Cuban-American population that does not share its parents’ vehemence. Opening relations with Cuba may once again open the hearts of these voters to the Democrats.

U.S. President Barack Obama (L) greets Cuban President Raul Castro (C) in Johannesburg in 2013. (Reuters)

Looking to the future

It was a handshake that almost upstaged the main event: the funeral of Nelson Mandela. A year and a week ago, Barack Obama shook Raul Castro’s hand, the first such public handshake between a U.S. president and a Cuban one since the revolution.

The symbolic gesture followed many more substantial changes. Cuban-Americans have been able to visit relatives in the country and send money home for a few years (the new changes announced Wednesday include an increase to the amount of remittances). The impact of the policy shifts from the United States have been amplified by equivalent changes in Cuban government policy. Money from relatives abroad has been used to open restaurants and businesses, renovate dilapidated homes into bed-and-breakfasts and buy new cars that can chauffeur tourists around in air-conditioned comfort.

Casinos in Havana? Not if, but when.

SIMONA CHIOSE

The Globe and Mail

Published Wednesday, Dec. 17 2014, 10:07 PM EST

Last updated Wednesday, Dec. 17 2014, 10:07 PM EST