Employees working at Starbucks in Toronto on Jan. 21, 2020. The company revealed to The Globe and Mail that it is working to find an alternative in its Canadian stores to black plastic cutlery – which is not recyclable. MELISSA TAIT

Starbucks is promising to cut its carbon emissions and waste in half by 2030, a goal that would require major changes from the global coffee chain that sells the majority of its products in disposable packaging – including its iconic to-go cups that end up in landfills in most markets.

The company also revealed to The Globe and Mail that it is working to phase out black plastic cutlery, which is not recyclable, in its 1,600 Canadian stores by the summer.

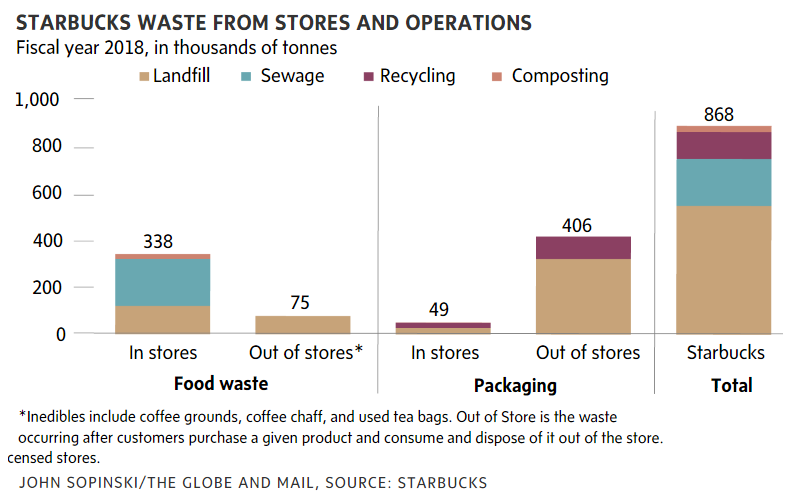

On Tuesday, Starbucks released the findings of a recent assessment of its environmental footprint. In 2018, its own global operations as well as vendors in its supply chain produced 868,000 tonnes of waste, used one billion cubic metres of water, and emitted 16 million tonnes of greenhouse gases – the equivalent of nearly 40 billion miles driven by the average passenger vehicle.

In 2018, Starbucks, as well as vendors in its supply chain, produced 868,000 tons of waste. MELISSA TAIT

The assessment by sustainability consulting firm Quantis is the first to measure the company’s footprint in all three areas globally. Starbucks’ largest emissions category is dairy, at 21 per cent; packaging accounts for 6 per cent. Globally, 18 per cent of Starbucks packaging is recycled, 64 per cent ends up in landfills or incinerated, and the rest is categorized as leakage, such as litter and ocean-bound waste.

In a public letter on Tuesday, Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson said the company aspires to store more carbon than it emits, eliminate waste, and provide more clean water than it uses. He said the environmental commitment – the company’s largest to date – will require expanding plant-based menu options, shifting from single-use to reusable packaging, and investing in reforestation, among other strategies.

“By embracing a longer-term economic, equitable and planetary value proposition for our company, we will create greater value for all stakeholders,” Mr. Johnson wrote.

The company, which has more than 31,000 stores worldwide, has already made some changes. Last summer, it introduced a strawless lid for its iced drinks in the United States and Canada; it plans to phase out straws worldwide by the end of this year. It is offering a discount for beverages in reusable cups in some markets.

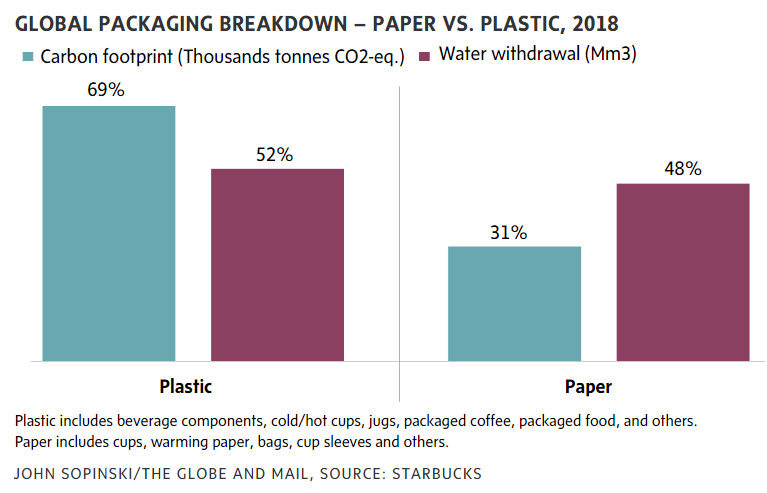

The Quantis report shows that polypropylene, which is used for cold cups, lids, straws and splash sticks, is Starbucks’ largest source of packaging waste. Paperboard, which includes signs and boxes, is the second-largest. Cupstock, which is the paper portion of the hot-beverage cup, is third-largest. (The cup’s liner is made out of polyethylene). Starbucks distributes six billion disposable cups each year, or 1 per cent of the 600 billion worldwide.

The use of plastic packaging has grown, because it is cheap to make and extremely lightweight – making it less costly and more fuel-efficient to ship. However, only 9 per cent of plastic in Canada is recycled after it is used, according to a report last year by Deloitte for Environment and Climate Change Canada. And nearly half of all the plastic waste in Canada comes from packaging.

The guilt that many people feel over their purchasing habits has become a branding problem for companies that sell them products in all that disposable packaging. Tim Hortons, which manufactures roughly two billion single-use cups per year, is planning a major marketing campaign to encourage customers to adopt reusable cups.

It is likely that companies will pass on at least some of the costs of environmental initiatives to consumers, said Dalhousie University professor Sylvain Charlebois, who researches food distribution. “The luxury that Starbucks has that other chains may not have, is that … people expect to pay more,” he said. “If they need to raise their price point … just to cover the cost of their cup, they can. But other competitors like Coffee Time, or Dunkin’ Donuts, or Tim Hortons can’t do it.”

The company is not the only chain that has recognized the need to address concerns around packaging and waste – both for environmental reasons, and because there has been a shift in consumers’ attention to sustainability issues.

MELISSA TAIT

Retailers as big as Starbucks have the market power to change consumer behaviour, said Diane Brisebois, CEO of the Retail Council of Canada. “It is groundbreaking,” she said, likening Starbucks’ commitment to the move among retailers to phase out plastic bags.

Pressure from investors is also building. Last week, Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, wrote in his annual public letter that his fund would challenge management teams to provide detailed plans on how they intend to tackle climate change. BlackRock is the world’s biggest asset manager, controlling nearly US$7-trillion in investments.

“[The investment community] is consistently looking for enhanced and transparent reporting of our environmental impact and environmental risk,” said Rebecca Zimmer, Starbucks director of global responsibility.

Starbucks must balance its sustainability goals with a business built on customer convenience. For example, the chain has courted customers by offering quicker service through mobile ordering in advance – a practice that depends on single-use packaging.

Mr. Johnson conceded that the company’s past environmental pledges were too dependent on “radical changes in customer behaviour.” Starbucks will conduct market research before it formalizes its 2030 goals next year.

Only 1.3 per cent of its beverages were served in reusable cups in 2018, according to Starbucks. This alone saved 42 million disposable cups. Canadian stores already make reusable mugs available for in-store use, but customers need to ask for them.

Starbucks has also promised to develop 100-per-cent compostable and recyclable cups by 2022. It is part of the NextGen Consortium – a group of companies that includes McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and Nestle – which is testing green cup technologies.

Ms. Zimmer said a key challenge is that materials that are recyclable or compostable in one city might not be in another. The chain’s to-go cup is only accepted for recycling in about a dozen major cities (Vancouver among them). According to Ms. Brisebois, the patchwork of waste-management standards is a frustration among many retailers working to improve packaging.

KATHRYN BLAZE, BAUMENVIRONMENT REPORTER

SUSAN KRASHINSKY ROBERTSON, RETAILING REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, January 21, 2020